Image Source: 401(K) 2012

The “5 Cs of credit” — character, capacity, capital, collateral, and conditions — is a widely-followed framework and generally-accepted guideline for lending to consumers, but for corporate entities, we think another C is much more important: confidence.

By Brian Nelson, CFA

The financial sector, and the underlying banking industry in particular, is distinctly different than most other sectors like industrials, retail, or healthcare, for example. Unlike the latter industries, banks use money to make money (net interest income), instead of using operating assets like property, plant and equipment (PPE) and raw materials to drive revenue and resulting free cash flow. This means that continued access to money and credit is the primary source of banks’ economic returns and more specifically their survival.

The “5 Cs of credit” — character, capacity, capital, collateral, and conditions — is a widely-followed framework and generally-accepted guideline for lending to consumers, but for corporate entities, we think another C is much more important: confidence. In almost every situation where a bank has encountered trouble, it has resulted from a loss of confidence in the sustainability of the entity as a going-concern. The loss of confidence could originate from counterparties, intermediaries, depositors or clients, or from any other core stakeholder. Lack of confidence typically spreads quickly.

Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy filing in 2008, for example, was accelerated by clients leaving the firm and credit rating downgrades that completely obliterated market confidence in the sustainability of the entity. Barclays now owns Lehman, which had been a staple in American society since its founding in 1850. Washington Mutual had its foundation rocked that same year when its customers, over a period of just 9 days, withdrew ~$17 billion in deposits, or about 10% of its total deposits, in the modern-day equivalent of a bank run. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation seized Washington Mutual and sold the 120-year-old company to JP Morgan (JPM) shortly thereafter. In both cases, the loss of confidence prompted disaster, leaving shareholders with only a fraction of their invested capital.

Quite simply, if the market does not have confidence in a banking entity, that banking entity will cease to exist. Though other business models such as master limited partnerships and real estate investment trusts depend on continuous access to the credit markets and incremental capital, a run-on-the-bank dynamic is a risk that is almost entirely unique to banks. FDIC insurance does not cover the financial products that a bank offers, including stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and life insurance, and the standard FDIC insurance amount is $250,000 per depositor, per insured bank. Because the government cannot insure everything and plan for all risks, traditional run-on-the bank dynamics can never be completely hedged away, no matter how advanced or regulated the banking system becomes.

An insufficient capital position brought about by excessive risk-taking (leverage), poor lending standards, and under-water loans as a result of asset declines may be more tangible operating reasons for a bank’s failure, but without confidence, even strong banks cannot survive. This important concept of confidence is in part why the Federal Reserve mandates annual “stress-tests” on the largest US banks. Any bank holding company (BHC) with more than $50 billion in total consolidated assets and all non-bank financial companies designated by the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) are subject to the testing, which breaks into two related programs: the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) and Dodd-Frank Act supervisory stress testing.

Per Dodd-Frank Act Stress Test 2016, June 2016:

• The Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) evaluates a BHC’s capital adequacy, capital planning process, and planned capital distributions, such as any dividend payments and common stock repurchases. As part of CCAR, the Federal Reserve evaluates whether BHCs have sufficient capital to continue operations throughout times of economic and financial market stress and whether they have robust, forward-looking capital-planning processes that account for their unique risks. The Federal Reserve may object to a BHC’s capital plan on quantitative or qualitative grounds. If the Federal Reserve objects to a BHC’s capital plan, the BHC may not make any capital distribution unless the Federal Reserve indicates in writing that it does not object to the distribution.

• Dodd-Frank Act supervisory stress testing is a forward-looking quantitative evaluation of the impact of stressful economic and financial market conditions on BHC capital. This program serves to inform the Federal Reserve, the financial companies, and the general public of how institutions’ capital ratios might change under a hypothetical set of economic conditions developed by the Federal Reserve. The supervisory stress test, after incorporating firms’ planned capital actions, is also used for quantitative assessment in CCAR.

In the spirit of preventing another global credit catastrophe, every year the Federal Reserve projects the balance sheet, risk-weighted assets, net income, and resulting post-stress capital levels and regulatory capital ratios over a nine-quarter “planning horizon” of banking entities that qualify for the stress tests. The projections are based on three hypothetical macroeconomic scenarios (baseline, adverse, and severely adverse), which are developed annually by the Federal Reserve. Qualified companies must also conduct their own stress tests periodically and submit them to the Federal Reserve.

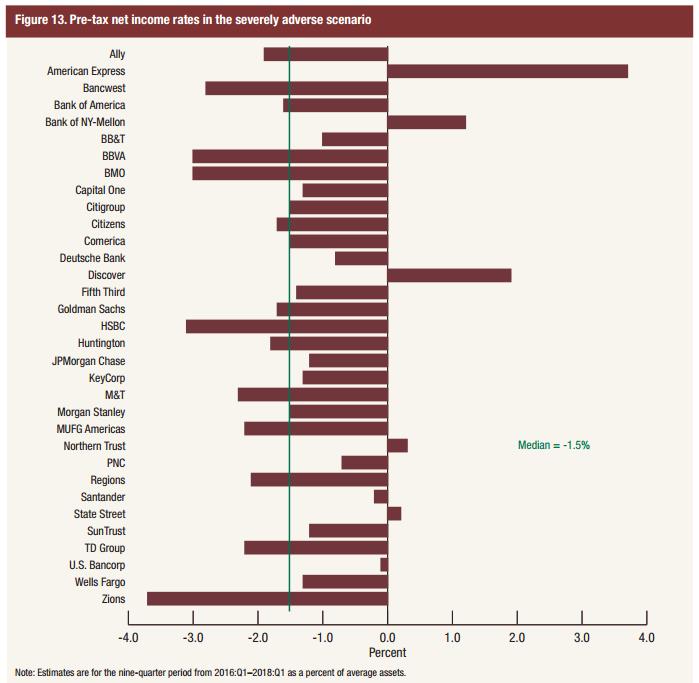

The projected pre-tax net income rates of “covered” banks in the severely-adverse scenarios of the Federal Reserve’s June 2016 stress tests areas follows. We find the table to be quite informative in revealing which banking entities would be most resilient in the face of broad-based economic weakness, falling asset prices, and rising unemployment.

Image Source: Dodd-Frank Act Stress Test 2016, June 2016

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the credit-card companies, American Express (AXP) and Discover (DFS) can handle severe adversity the best, followed by Bank of NY-Mellon (BK), Northern Trust (NTRS), State Street (STT), and to a lesser extent US Bancorp (USB). We would expect these entities to fetch premium prices in the marketplace due to a lower cost of capital and relatively muted uncertainty associated with their operations.

On the other hand, the opposite dynamics should hold true for Zions (ZION), HSBC (HSBC), Bank of Montreal (BMO), and BBVA (BBVA), which are projected to experience comparative higher loss rates in the event of severely-adverse economic and credit conditions.

Jul 5, 2016

The Next Banking Crisis? No… Well, Not Yet.

We’re hearing about run-on-the-bank dynamics in the UK. We think a market disruption may be nigh, but then again, it might not. “Things” are still developing.