Member LoginDividend CushionValue Trap |

Repub from July 2019 -- The Valuentum Economic Roundtable

publication date: Apr 3, 2020

|

author/source: Valuentum Analysts

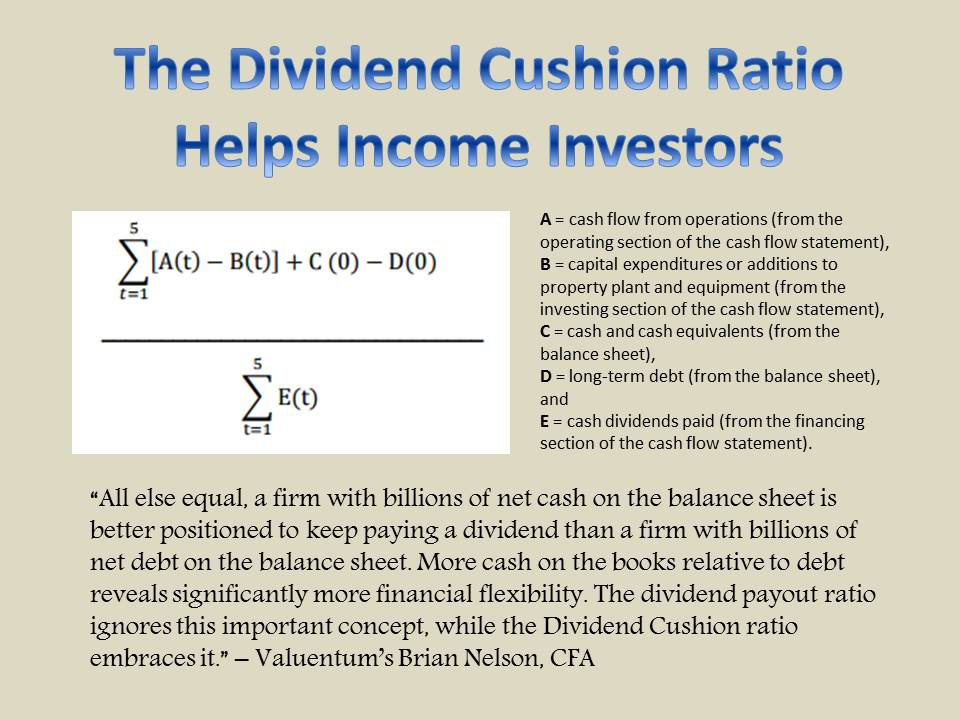

This article was published July 23, 2019. We sat down with the Valuentum team to get their thoughts on the global economy and key issues that may threaten this near 10-year bull market. Let’s start with Valuentum’s Bank and Financials Contributor Matthew Warren, and then we’ll go around the horn. Matthew Warren: It’s interesting what’s happening at the nexus of the consumer and various retailers. It reminds me of the pockets of discretionary weakness back in 2008. I made money on Men’s Warehouse (TLRD) puts back then. Nobody is really in a rush to buy a suit, especially if they are concerned about their job prospects. At least we only have CLOs (collateralized loan obligations) and Europe/China stress to ponder over this time. Much less stress if corporates hit balance sheet troubles as compared to a housing finance catastrophe last time. I hope Europe can limp along regardless of what may go down in China. If we all get dragged into deflation, then we are really in trouble. Let’s hope that remains a tail risk. Brian Nelson: I've been very skeptical of this monetary-policy-led recovery all these years, though stocks aren't terribly overpriced if forecasts do come to fruition. What I struggle with is the concept of NIRP (negative interest rate policy). If there is no zero bound to the cost of borrowing, then how should we think about valuation. Stocks could truly reach bubble levels if discount rates approach zero as a result of the possibility of NIRP policy. I feel like there has to be some self-correcting mechanism that would punish moral hazard, but has one of the lessons of the Financial Crisis been that moral hazard is not punished? Will the Fed just continue to bail out the markets time and time again? That interest rate lever is a big one, and the Fed may very well have the markets in the palm of its hand. Many weaker retailers, clothing and apparel, particularly mall-based may not make it to the other end of the next recession. Even some of the department stores may see their equity pummeled, even some of the stronger ones like Kohl's (KSS), Nordstrom (JWN) and Macy’s (M). J.C. Penney (JCP) has almost reached its end. Some of the full-service restaurants could make for some great short-idea considerations. What is interesting is that as we follow many of the consumer staples equities, many of them are trading at 20+ times forward earnings with net debt on the books and muted growth. McDonald's (MCD) and Clorox (CLX) seem very pricey. It's very difficult to get to their prices with a DCF (discounted cash-flow model). Consumer staples stocks may turn into the Nifty Fifty of years past. If we do enter another recession with tightened credit, credit-market dependent equities may fare the worst (low quality REITs, MLPs and those paying out more in distributions than they generate in FCF), as they did during the credit crunch. Highly-leveraged corporate equities, too. $22 trillion in sovereign US debt; $6 trillion in corporate debt; negative interest rates across the globe, and the US feels like nothing in the world quite matters, not even too much related to a trade war with China. It's hard to put one's finger on the exact catalyst that may unwind this 10-year bull market, but the market and/or yield curve invesion itself could be one (if only for its psychological implications). If people sell because they think an inverted yield curve is a precursor to recession, selling of stock and pulling back discretionary spending as a result may actually cause the recession. The markets may then correct, and we could see a multi-year unwind, but even still, it would seem the next recession may only be minor, unless something really unfolds as in a breakdown of market structure, something I talk about in Value Trap. Matthew Warren: Regarding NIRP (negative interest rate policy), it's hard to argue with the impact on valuation (via both cheap borrowing and the equity discount rate). Warren Buffett concedes that if you knew rates would stay this low for a long time, then stocks are in fact a bargain. However, a big part of me thinks that if you model the low cost of capital that comes with NIRP into perpetuity, then you should also model weak top line growth that comes with a very stagnant economy. Isn't that the lesson of Japan? Isn't that where Europe seems to also be headed as well? Is the US also headed down the same road? I do think there is a limit to the effectiveness of NIRP in terms of stimulating the economy. Look at auto sales (even with low rates) appearing to get very tired. Look at credit cards and student loans. Is there really much more creditworthy demand that can be stimulated with low cost debt? If anything, it appears the banks have to charge a large (credit-card) NIM for the risk/reward to be enticing, at least in their aggregated opinion. It ends up being a debt trap for those that take on too much, and then they are stymied by debt service--in many cases for life. The high valuations on equities, bonds, and other assets certainly create a wealth effect for the small minority of the population that owns those assets in a size that is material to their overall situation. But with that comes inequality, and of course the rich don't have the same propensity to spend as those with lesser means. The basic concept that capital's higher returns than wage inflation will cause wealth to accumulate and stoke inequality almost seems inevitable. And historically, does inequality ever correct itself without a depression in asset prices? Granted this might be a very long game I am referring to here and not something for this year or even the next decade? Of course we can go without recession for some time. I don't see why not. The banks do not appear to be sitting on a mess like they usually are as a precursor to recession. You mention the circular nature of a stock selloff itself causing a recession, and I think you are spot on. That's why the Fed gets involved every time we get a 20% pullback. Talk about the tail wagging the dog! I agree that marginal retailers and full-service restaurants make for good short idea fishing. I just read Nordstrom's conference call earlier this week, and it sounded pretty pathetic. I think the Nifty Fifty in bond-like stocks can be partially justified. I have thought for a while that I would rather own a staple with pricing power rather than a long government bond with fixed payments. I think a bullet-proof staple with substantial pricing power and substantially inelastic demand for its products should have a lower cost of equity closer to that of bonds than a full 10% cost of equity. If you think about McDonalds, I know California is an extreme example, but that is one of the only places where you can feed yourself for 5 bucks (AND ONLY IF you buy one of the rotating sales items). In good times, there are people (working poor and those sticking to a budget) trying to eat cheap and in bad times, there are additional people trading down to eat cheap. I don't think that means you model huge growth or margins different from what they have experienced, but what is the right cost of equity for a company in this position? If the market were to give you a full 10%, I would take that over 2.3% Treasury bonds every day of the week. Brian Nelson: Tremendous insights. Thank you Matt. Callum, what has been on your mind with respect to recent economic readings? Callum Turcan: While the official (U-3) seasonally adjusted unemployment rate in America stood at 3.6% in April 2019 (from the Bureau of Labor Statistics), note that the U-6 measure of unemployment (seasonally adjusted) was significantly higher at 7.3%, as one would expect. However, also note that America's labor force participation rate stood at 65.7% of the working age population in January 2009, before crashing lower to just 62.8% as of April 2019 (far below the 1990s-2000s average). It's conceivable there is more slack in the labor market than America's very low official unemployment rate would suggest (as has arguably been the case for the better part of this decade), which has been depressing wage growth for some time (until more recently). The BLS reported that hourly wage growth hit 3.2% year-over-year in April 2019, while weekly wages were up 2.9% year-over-year. Whether or not American hourly wages continue to grow over 3% annually may depend on how trade wars and potential interest rate cuts pan out, as the supposedly hot jobs market hasn't yielded the kind of wage growth (over the past decade) one would suspect in a truly tight labor market. Please note that the given wage growth figures are not adjusted for inflation and that the CPI-U stood at 2.0% in April 2019, depressing real wage growth significantly. A material reduction in the nominal wage growth rate, due to weakening macroeconomic conditions, could lead to real wage growth reaching close to zero (from roughly ~1% as of April 2019) in the aggregate (distribution effects are a different story). Brian Nelson: Interesting. Let’s now address a few questions from members. Here goes: What are your thoughts on the possibility of a recession coming sooner than anticipated based on: 1) Recent series of interest rates hikes in the US--on the monetary policy side, the Fed’s 13 tightening cycles since WWII, 10 have pushed the economy into a slowdown or a recession. 2) Rate of publicly traded companies buying back their outstanding shares – unprecedented debt-for-equity swap done this cycle, borrowing at low interest rates and buying back their stocks, and 3) Bond yields have come down and yield curve has flattened? Matthew Warren: As it relates to the first question, the Fed has been trying to normalize rates as much as possible against the backdrop of a benign macro situation, hoping the yield curve would remain stable and upward sloping. After all of the QE by the Fed and other monetary institutions around the world, it amounted to an experiment to see how much the real economy could handle more normalized rates. The experiment began to fail at higher levels of short rates above 2%. The housing and auto economies both started to slow as higher rates began to impact demand. The yield curve ultimately inverted as a result, as market participants began to fear an outright recession as a result of the higher rates. This of course has led to "the pivot" by the Fed, basically going on pause instead of the future hikes that they had been discussing. This brought long rates back down and relieved some of the burgeoning stress, especially on the housing market--at what amounts to high housing prices in many of the hotter markets around the country. Time will tell whether past hikes cause further problems and whether the Fed ultimately needs to cut current rates, which the Fed Futures market has now baked in. What is clear is that there is a lot of debt in the world, especially government and corporate debt, and there is a level of rates that begins to cause stress. I think the Fed has learned that lesson. Brian Nelson: Regarding the second question, I do think there should be some cause for concern as it relates to the hundreds of billions in buybacks, if not trillion-plus in share repurchases in recent years. There is a school of thought that suggests the price of the stock just doesn’t matter, since those selling shareholders are benefiting from the high prices at which the company buys back its stock. It’s an interesting perspective, but we tend to favor the school of thought that suggests that buybacks should serve to benefit the majority of shareholders, which are almost always continuing shareholders, or those not looking to shed shares. That means we’d prefer companies buy back stock below levels of reasonably estimated intrinsic values. Many companies are doing this today, but many companies are not. Likewise, not all buybacks are good and not all buybacks are bad, but many executive teams are using buyback programs in ways that may not benefit continuing shareholders. We’d much rather see companies accumulate some excess cash on the balance sheets and wait until the next downturn, the timing uncertain, to deploy that capital at much lower share prices to add considerable value relative to prices now nearly 10 years into a bull market. Many want executives to put cash to work right away, but we encourage management teams to be prudent and deploy capital only when the time is right. As many learned during the Great Recession, capital is not always readily available when it is needed the most. While it seems today that companies can almost borrow at will, credit conditions are far from static, and just like investors, we think companies should have some dry powder, too, in the form of cold hard net cash. When it comes to the inverted yield curve, I think the implications are more behavioral than anything else. The Fed doesn’t want to take steps to aggressively drive a further inversion of the yield curve, most likely due to what it might signal. People are worried about the yield-curve inversion, and therefore may take actions that actually cause a recession, actions that may have not happened had the yield-curve signal not happened. This is why we’re starting to hear the Fed talking about cutting rates, in my opinion. Matt, anything further to add? Matthew Warren: I would like to emphasize a risk to the system I mentioned earlier in leveraged loans and corporate/business debt levels. While I think most banks haven’t been overly aggressive in lending to businesses and corporates on balance sheet during this cycle, I do think that the $1.1 trillion levered loan market--often packaged into collateralized loan obligations (CLOs)--has been aggressively lending to corporations, with fewer and fewer protections for the lender. The borrowing companies are generally junk status and paying higher interest rates than you would find with investment grade bonds for instance. In a recession, many of these companies could fall further into junk status and face real difficulties in servicing their high debt levels. It is not hard to picture that the credit markets could tighten (higher rates and more covenants) or even seize up for some of the more levered firms, leaving them stranded. If these firms were unable to roll over their high debt levels, they would be forced to pay back debt as it came due or face distress. If many of these companies either went bankrupt or were forced to radically de-lever their balance sheets, they would not have the funds available to reinvest in their businesses, denting economic growth. Those institutions holding the debt would also face substantial losses, especially as much of this debt is held in levered investment vehicles outside the banking system, amplifying losses in a downturn. Banks do have exposure in that they underwrite and sell on a lot of levered loans and could get caught with loans in inventory if the market seized up quickly. They also lend to investment vehicles that hold these loans and have exposure there. In my judgment, I think most banks have managed the amount of this exposure relative to their capital levels, meaning most of the stress in a severe recession would fall on the borrowing companies and the holders of levered loans themselves, most of which is outside of the regulated banking system. Still, the growth and sloppy underwriting in the levered loan market is a risk that bears watching. Brian Nelson: Callum, what are some of the signals the energy markets are giving us? Callum Turcan: With the 12-month West Texas Intermediate futures curve plummeting from an average price of mid-$60s per barrel a few months ago down to the low-$50s as of June 6, watch out for potential capital expenditure reductions in America’s shale patch. A combination of pressure from oil & gas investors seeking a more disciplined approach to capital allocation on top of already weak balance sheets could potentially force US upstream independents to scale back spending by a lot if oil prices don’t improve (particularly the small- and medium-sized players). This may act as a modest headwind to American economic growth, particularly if economic activity slows down in major oil producing regions that heavily utilize hydraulic fracturing technology (including states like Texas, Oklahoma, North Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado, and more). States that produce or are prospective for a material amount of natural gas liquids, such as Ohio and Pennsylvania (through the Utica and Marcellus shale plays), could also be negatively impacted. The negative impacts could potentially involve layoffs, reduced tax receipts (production taxes are a major revenue source for many local and state governments), reduced drilling & completion activity (which feeds into the layoffs), potential cuts in local/state government expenditures, cuts in local/state government services as a byproduct of spending cuts, reduced property values on a regional basis, and higher levels of credit write-offs (specifically for regional banks). Brian Nelson: Thank you for your thoughts everyone! Be sure to leave your comments below! ----- Comment below or submit your questions about the economy to info@valuentum.com, and our team will cover it in the next Valuentum Economic Roundtable. Tickerized for holdings in the SPY. --------- Valuentum members have access to our 16-page stock reports, Valuentum Buying Index ratings, Dividend Cushion ratios, fair value estimates and ranges, dividend reports and more. Not a member? Subscribe today. The first 14 days are free. Some of the companies written about in this article may be included in Valuentum's simulated newsletter portfolios. Contact Valuentum for more information about its editorial policies. |

6 Comments Posted Leave a comment