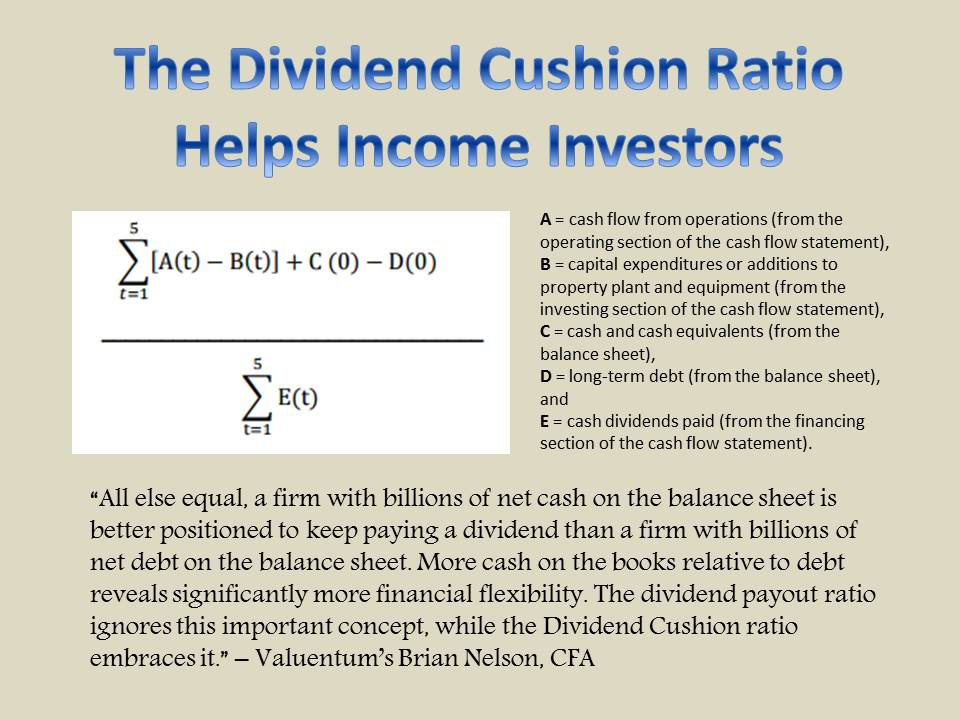

Member LoginDividend CushionValue Trap |

Primer on the Banking Sector: Where Are We in the Cycle?

publication date: Nov 25, 2019

|

author/source: Matthew Warren

Image Source: GotCredit Three of our favorite banks are JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and US Bancorp. These are three very high-quality institutions which are also very well managed. They all benefit from cultures that encourage the right kind of risk/reward thinking. If these equities start to trade at a meaningful discount to our fair value estimates, they may be are worth considering as long-term investments, in our view. Summary We’ll talk about how banks make money, and the three most important costs of running a bank. The Great Financial Crisis revealed the tremendous risks of banking equities, and we’ll walk through these in depth. We’ll discuss how to conceptualize where we are in the banking cycle, and how that helps inform our valuation process for banks, which is different than traditional operating entities. The stress tests have helped many of the big banks from pursuing hazardous endeavors during the past decade, and we’ll go into how to think about the yield curve in the context of banks. Investors should expect ongoing digitization of banks and increased M&A as the competitive environment only intensifies. Three of our favorite banks are JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and US Bancorp, and we’ll be looking to consider adding any of these to the Best Ideas Newsletter portfolio or Dividend Growth Newsletter portfolio at the right price. By Matthew Warren How Do Banks Make Money? In order to understand where the big banks stand right now, it might be helpful to start at the very beginning. How do banks make money? Banks essentially make money on money. They collect money mostly in the form of deposits, often at a very low cost--such as zero interest checking accounts. Certificates of deposit (CDs) and corporate deposits cost more than nothing and borrowing in the bond market costs even more than that. Even when no interest is paid on transactional accounts, there remains a cost to these funds as services are being offered to those clients “for free.” While banks have a cost of funds, they then turn around and lend out some, all, or more than their deposits to the public whether in the form of credit cards to retail clients, small business loans, construction finance loans, or loans to giant multi-national corporations. The spread between the revenue earned lending and the cost of those funds is called the net interest margin (NIM), which is often about 200-300 basis points for a large bank, depending on the mix of business. Banks also earn non-interest revenue in the form of banking fees, commissions, and the like. Adding net interest income to the non-interest revenue arrives at the net revenue of the bank; subtracting non-interest expenses (starting with bad credit costs) from this, one gets down to the pre-tax income line. Three Key Costs of Running a Bank This quick introduction to banking makes it clear the three key areas where banks must control their costs, especially given that US banking is largely a commodified industry. In a commodified industry, it is the sustainable low-cost leaders that can eek out returns above the cost of capital. One, the cost of deposits is the first key cost to control. Banks with large, low cost deposit bases such as JPMorgan Chase (JPM), Bank of America (BAC), and Wells Fargo (WFC) enjoy the leading US deposit franchises. Two, the cost of credit is the next key cost to control. Over the course of time, banks that are lending in the exact same space such as auto lending can experience wildly different credit costs. While some of this can be due to the risk/reward tradeoff being pursued by management, it can also reflect the success or failure of underwriting each individual loan, which ultimately creates the aggregate loss experience. Underwriting quality stems from the underwriting culture of the bank, which starts right at the top with the CEO steering the ship. Is risk or reward being emphasized to middle managers and the rank and file? What kind of targets are financial incentives and promotions based upon? How is risk versus reward talked about inside the bank? Underwriting culture is driven by all layers of management and is not quick or easy to change on a dime. It is more like turning a large ship. It is individual human decisions that we are talking about after all and old habits die hard. Not only is there an underwriting culture that drives credit costs (bad debt expenses,) but it is also a bank’s culture that drives the third major cost center, which is operating costs, as measured by the all-important efficiency ratio--operating costs over net revenue. The efficiency ratio is also very much affected by business mix. Stock brokerage comes with very high efficiency ratios as does high service commercial banking relationships, while mass market retail banking comes with much lower efficiency ratios. That said, if business mixes are similar, the bank with the lower efficiency ratio is the one that is accomplishing the same revenue dollar with less cost associated. The Risks of Running a Bank The risks of running a bank are many-fold. The first and most important thing a bank CEO can get wrong is the culture of the bank. Culture touches everything from how a bank operates, to the ultimate fundamental results, and even the valuation analysts and investors are willing to place on the firm. Wells Fargo used to trade at a premium and now trades at a discount to peers, and questions around the culture are a key element in that change. Every bank management team wants revenue growth. The question is how do you get there? Are you willing to sacrifice near term earnings trajectory as you invest in new markets and new salespeople? Or does your growth come simply by taking more risk for the same level of reward? The former is a tough decision for public bank managers to take as it can negatively affect the share price and management options in the short run. The latter is like a siren song. If you get the same reward for riskier new business, the near-term financials show faster growth with similar credit costs in the short run. In time, however, perhaps even as late as the next recession, the greater risk being taken ultimately will show up in the credit cost line on the profit and loss statement. The run up to the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) provides the perfect example of bank culture and risk versus reward. While massive home price appreciation was allowing folks to use their home as an ATM and paper over any income deficiencies, it seemed most all banks could do no wrong. Revenue growth was stronger than usual and credit costs were largely benign. A key hint for those paying attention was the subtle but not insignificant differences between credit losses for those banks operating with similar business mixes. As it turned out, the banks growing the fastest on the back of subprime mortgages and subprime mortgage-backed collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), which were starting to show slightly larger losses even prior to the peak, were the first banks to get blown away when the housing market melted down from excesses boiling over. What might have seemed like minor differences at the time, turned out to measure the difference between failure or tough times--before a full rebound to health. Amongst the money center banks, JPMorgan turned out to be sitting on a lot less risk than Bear Stearns, Lehman, or Citigroup (C). This brings us to another risk of investing in bank stocks. Bank balance sheets can be appropriately characterized as somewhat opaque. Loan books are broken down by industry and by credit quality as determined by the bank, but that doesn’t mean that a large bank cannot hide a busted deal on their balance sheet without anyone really knowing. If a deal was originated with intent to distribute, but it ultimately falls through--for example because the cycle is changing on a dime—there is nothing to stop the bank from parking this loan on the balance sheet. In fact, this is exactly what happened with busted collateralized debt obligations (CDO) and Commercial Real Estate deals back when the GFC hit. The amount of speculation about the big banks opaque balance sheets came to a fevered pitch. Banks didn’t trust each other, and investors lost faith in what was contained on balance sheet. This fed the fear in the marketplace and increased counterparty risk. This caused banks to stop lending as much to each other and further fed the liquidity crisis that was taking place at the time, causing the Federal Reserve to be forced to step in to help with bank funding. Trust matters in banking, and if investors and counterparties come to think a bank is hiding things on its balance sheet, real trouble can ensue. Speaking of counterparty risk, another key risk of running and investing in banks is the counterparty risk that comes from large, opaque derivative books. Notional exposure amounts are disclosed, and the banks will tell you that exposures to any particular bank are kept to reasonable levels. That said, if there is a global run on banks like was starting to take place in the GFC, the risk of several banks failing at once can emerge. Derivative books make banks more intertwined and increases the knock-on effect of bank failures. If hedges fall away, banks must scramble to put those hedges back in place. It can create chaos in the derivatives market, and it can certainly create doubt about the efficiency and effectiveness of the hedging programs that banks have in place. The Risk of Outsized Growth Growth is good, right? Usually the answer to this is a simple yes. When it comes to banks, however, the answer becomes a bit more nuanced. Sustainable growth is good. Growth that the market allows for is good. Organic growth from adding productive geographies and salespeople and products is good. However, loosening underwriting standards to hit a revenue growth target that management has foolishly sold to Wall Street can lead to full blown disaster. It is up to management to lead the bank in the right direction and communicate appropriately to employees and other stakeholders. Beware of growth hype from management when it comes to a bank. It is up to the analyst to judge the quality of growth that they are witnessing at a particular bank. Sometimes, it is the bank that is leaving growth on the table that will outperform in the coming downturn. Other times, banks can be left behind when management is afraid of its own collective shadow and is not willing to grow with the market. The bottom line is that these are judgment calls. Look for logical descriptions of where the growth is coming from. Watch the bank’s key metrics to make sure they are not giving up NIMs or credit costs in order to achieve growth. Watch for the warning signs and retain a healthy skepticism. Where are We in the Cycle? This is a question that every bank manager, analyst, and investor must ask and answer for themselves, even if the answer is: I’m not sure. When bank performance is suffering from the downcycle and results are accelerating to the downside, it can be a scary time to invest in banks. The best thing to do is to try to make judgments about how much bad credit is contained on a given banks balance sheet and whether earnings and capital can offset these pressures to get through to the other side. If in the case of the GFC where the downside is large and unknown, it is often best to stick to high ground banks with the strongest balance sheets and earnings power. Don’t worry about finding opportunities as these banks have probably sold off, too. High ground banks are more likely to be “double down” stocks, which is a rare thing among banks. If the worst of the cycle has been left behind, the question then becomes: where are we relative to the next downcycle? Are current earnings reflective of what can be characterized as mid-cycle or normalized earnings? If so, putting an appropriate valuation on those results will lead to better outcomes. Are earnings outsized because revenues are benefitting from good times and credit costs are abnormally low or even near zero? If so, it is important to scale back to mid-cycle revenue trends and margins before fully valuing an earnings stream into perpetuity. Another question to ask is: where are the excesses that are building up and how bad are they? How much loss content is being stored up for the next downturn? A prime example is the GFC when subprime mortgages were being written very rapidly and turned into CDOs, which were highly rated but ultimately completely suspect. The larger these revenue streams became and the larger these positions became on bank balance sheets, the more danger was lurking for when the the cycle turned, and losses showed up in rapid fashion as folks could not afford the homes that they had stretched for without proper income and/or documentation. The ratings on the flood of Wall Street paper quickly downgraded to junk. A current example would be collateralized loan obligations or CLOs. These are levered loans where companies are borrowing substantial sums of money where debt is a large multiple of EBITDA (cash flow before several important costs) and interest payments are a large part of cash flow. These CLOs have grown substantially in size and are largely held outside of the banking system. However, if the music stopped quickly, the banks that are underwriting these loans could easily get stuck with inventory. It is a risk to watch. Sometimes, the question of where we are in the cycle will give no definitive answers, which may be informative, nonetheless. It may indicate that the industry is not at the trough and probably not at the peak of the cycle. It suggests that the industry may not see any large piles of old or new risks that can hit the P&L in a material way. It indicates that the revenue and earnings stream is more likely to be close to mid-cycle margins, deserving of a full valuation. So, where are we right now? As mentioned, we see risk in the CLO space. We also see risk in the commercial construction cycle and commercial property loans. WeWork (WE) has exposed a structural weakness and a very large weak player out there in many key large cities. Credit losses look abnormally low across the banking system, but especially in credit cards given the currently very strong consumer. Revenue growth has not been out of control, which is a good sign of moderation. As of this writing, we are 11 years into a bull cycle, and it will ultimately turn down due to one cause or another. Therefore, I think it makes sense to scale back the earnings power when valuing a bank’s equity at this stage in the cycle, which is exactly what we do here at Valuentum. Stress Tests Since the GFC, systemically important (large and interconnected) banks have been forced to go through annual stress tests, where sizable losses are hypothetically run through each bank’s P&L to see what impact there would be on capital levels. The idea is to determine what would happen to each bank in a recession and a more severe recession scenario. Would they still have the required capital after eating up the assumed losses against earnings and existing capital levels? This process has forced a certain discipline on banks these past ten years, and we would argue it has largely kept them in line from doing anything particularly reckless in the meantime. These banks must get their capital plans approved also, so they must stay in line if they want to pay out their dividends and perform the planned share buybacks to reward shareholders during this last decade of relatively slow revenue growth. Interest Rates, the Yield Curve, and Net Interest Margins Some but not all bank loans are tied to benchmark interest rates plus a margin. Therefore, in the short run, the amount they can charge customers varies accordingly with short rates. Another key factor is that zero rate deposits don’t tend to move much when rates change (endowment effect). Therefore, higher rates mean higher net interest margins on these deposits. These two factors mean that higher rates tend to mean higher net interest margins and vice versa. The banks disclose how much higher and lower rates will affect revenues and the profit impact can be imputed. That said, we think these short-term impacts can be overblown by the media and even analysts and investors at times. The reality is that the margin or spread changes with competition over a longer period of time. So, if rates are lower for longer, the banks can simply mark up the margin they charge over these lower rates and cycle through the book to better economics. Given that the overall industry tends to produce cost-of-capital returns on average over time, it suggests a competitive landscape and one that can adjust the levers of profitability to match the exogenous or uncontrollable factors like short-term rates and the shape of the yield curve. Therefore, beware when you hear oversimplifications in the media that banks borrow short and lend long and are simply price takers on both sides according to the whims of the yield curve. We would beg to differ, and we think results will prove out over time. Digitalization of Banking The digitalization that is taking place across so many industries has certainly been taking place in banking over the past decade. Think about how advanced mobile banking apps are now compared to where things stood a decade ago, when most people were in the branch or at the ATM. The digitalization is also simplifying processes in the back office, taking out people, making things more scalable and repeatable. The biggest banks with the most scale have the largest revenue streams and can afford to stay on top of this trend most easily while many small scale banks and credit unions are stuck in the past shuffling paper around and with unsophisticated or even no mobile app available. Therefore, this trend plays right into the hands of the biggest banks in the country. It helps them hold onto clients and win new clients and market share. It helps them deliver a better experience and free up branches for sales, while streamlining the back-office cost structure. This is a key trend that will help large banks and drive consolidation of market share within the industry Mergers & Acquisitions As of this writing, BB&T (BBT) is on track to acquire SunTrust (STI) and we don’t think this will be the last merger. Given the digitalization of the banking industry, scale matters even more than it already did. Retail banking, especially, is a scale game. Running large credit card operations is a mass marketing game and the back office certainly benefits from scale. Smaller banks have largely ceded this market to the larger banks already. With the digitalization trend pouring fuel on this fire, we expect M&A to continue apace. Since banks are not really undervalued as a whole, mergers of equals might need to be the path to success in scaling up to play with the big boys. Business Mix Having mentioned the upside of being a big bank, let’s also talk about a more questionable characteristic of most of the largest banks. Most of these institutions have large investment banking and trading operations. While this clearly is a benefit when it comes time to win over the largest corporate clients, as they can be a full one-stop shop for all of the clients’ needs, it also introduces a volatile and low return on capital earnings stream to the overall earnings mix. For the big money center banks, it is the bread and butter banking unit (especially retail banking) where the highest returns on capital are made and generally with the smoothest earnings streams (setting aside the GFC). Simply said, large scale retail banking operations deserve higher valuations. This can also be true of asset management and payment processing units for those banks that benefit from material operations on these fronts. Valuation Banking valuations can be very bi-polar throughout the market cycle. At the trough of the GFC, banks were being priced as if they were going out of business. Some in fact did. Therefore, it was no shock that most banks traded at a discount to tangible net asset value. The banks were being priced as if they would be wound down or as if there was a probability of survival and a probability of failure or permanent capital impairment. These weightings would change from day to day along with the macro assumptions about the magnitude and duration of the banking crisis and substantial economic downturn. Just before the GFC hit, analysts and investors were arguing that banks shouldn’t suffer from price-to-earnings (PE) multiples below the overall market. The case was being made that big earnings cycles were a thing of the past, these were growth stocks, and so, there should be no P/E discount? This was extremely flawed logic, which was quickly proven as things swung to the opposite extreme. And yet, we are hearing this case being made again today by some in the media. The right answer to us is that banks--that do not face the risk of permanent capital impairment--should be valued based on the premium or discount that they are able to earn relative to book value. It should be based on mid cycle revenue and margin trends. If a bank does face the risk of permanent capital impairment, at the very least one must introduce a probability-of-zero value into the overall value. More realistically, if this risk is material, the stock is simply un-investible as no one ever truly knows the magnitude and duration of any particular downturn in the banking cycle. Fragile banks can tumble like dominoes when things get bad enough. Bank Panics The problem with banks as opposed to operating companies is that very few (if any) are true “double down” opportunities regardless of the macro environment. In a bank panic or depression, it is extremely hard to tell which banks will suffer a crisis of confidence and a run on the bank by its various stakeholders. The GFC is the most recent example of this, but a down cycle or panic can in fact come in worse than that. Banks operate with significant financial leverage by their very business model. They borrow money to lend money. Most banks are levered approximately 10 times to 1. If the loss content in the assets becomes large enough, and the revenues come under enough pressure, it is like everything is going wrong at once. This is especially true for banks that are only marginal during the good times. They are simply closer to the tipping point in terms of failure. The other undeniable fact is that perception can become reality. Banks need their depositors to keep their funds in place. Banks need to rollover their market funding. If these conditions don’t hold, then a bank can face a liquidity crisis. Once a crisis of confidence starts, it is hard to arrest. In fact, without help from the Treasury and regulators, the GFC could have led to many, many more bank failures and a full-blown depression. So, investors at that time were left guessing what the next regulatory response would be and whether the medicine would be strong enough to turn around the systemic infection. It is hard to double down on even the strongest bank stocks in an environment like that and one could even argue that it is not as logical as doubling down on strong operating companies with rock-solid balance sheets where permanent capital impairment was essentially non-existent. The exception is for a player like Warren Buffett who by investing enough capital and committing to invest more can almost guarantee a bank’s survival. Regulatory Risk on Both Sides Regulatory risk could bite the banking industry from both sides. If de-regulation goes too far and the stress tests are thrown out, excesses could easily build up again in the banking industry, cowboy capitalism could ensure, and the next bank panic could follow. On the other side of the coin, some of the most progressive political candidates seem to still be gunning for the banking and investment banking world in the aftermath of the GFC and the consequences visited upon society. These risks bear watching but neither one seems imminent. Contagion from Offshore The biggest systemic risk that we see is contagion from offshore and specifically from Europe as these large banks are indeed interconnected with large US banks. If deflation or depression-like environments take hold in Europe (and to a lesser extent Japan), sovereign defaults and domino bank failures could cause severe stress on the global banking system. This kind of stress would certainly spill into the US market and economy. This risk is not easy to handicap but bears watching. Our Favorite Banks Three of our favorite banks are JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, and US Bancorp (USB). These are three very high-quality institutions which are also very well managed. They all benefit from cultures that encourage the right kind of risk/reward thinking. If these equities start to trade at a meaningful discount to our fair value estimates, they may be are worth considering as long-term investments, in our view. Tickerized for our bank equity and ETF coverage universe. ----- Valuentum members have access to our 16-page stock reports, Valuentum Buying Index ratings, Dividend Cushion ratios, fair value estimates and ranges, dividend reports and more. Not a member? Subscribe today. The first 14 days are free. Matthew Warren does not own a position in any of the securities mentioned above. Some of the other companies written about in this article may be included in Valuentum's simulated newsletter portfolios. Contact Valuentum for more information about its editorial policies. |

0 Comments Posted Leave a comment