Member LoginDividend CushionValue Trap |

Part I: Nelson’s Evaluation of Berkshire’s 2015 Annual Report

publication date: Mar 10, 2016

|

author/source: Brian Nelson, CFA

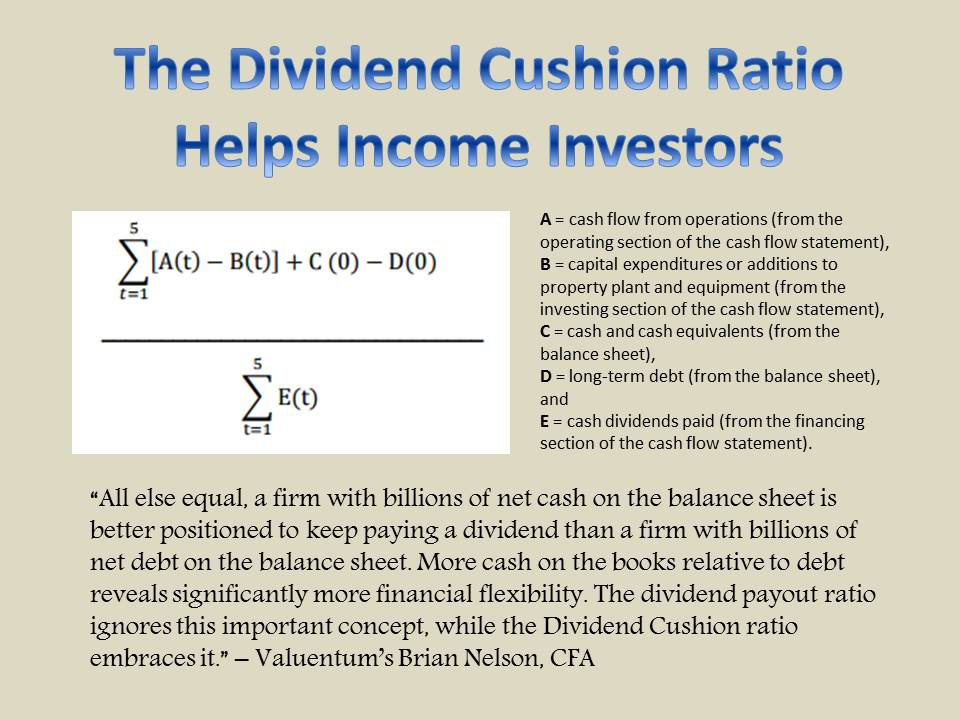

Image Source: Fortune Live Media By Brian Nelson, CFA It’s always fun to crack open the Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A, BRK.B) annual report, this year's 2015. It reminds me of how much times have changed. For one, if Warren Buffett had been starting out in the investment business today, he simply wouldn’t have had a chance. The front page of this year’s Berkshire Hathaway shareholder letter shows that he trailed the market 33% of the time in the first 6 years in business (1965-1970), and the company lost half of its market value in 1974. Very few fund managers today, if any at all, that lose half of their market value in one year, trailing the market by 22 percentage points in that same one year, will be able to stay in business. The demands are different. Warren Buffett preaches a lot of principles that just wouldn’t work today. As you may be able to relate, if Valuentum doesn’t absolutely blow the socks off a new individual during the first 14 days of his or her membership, we may lose a very, very valuable customer...forever…over a few pennies an hour. It happens sometimes, but while most usually come back after they peruse the investment research marketplace, some don’t. I simply couldn’t imagine losing half of the portfolio value of the Best Ideas Newsletter portfolio and Dividend Growth Newsletter portfolio and have most of the civilized world point to me as one of the best fund managers in the history of time. Yet, this happened to Warren Buffett. Times have certainly changed. This business today is brutal, and it will only get worse. I sometimes get not-so-nice emails about 1%-2% portfolio positions that didn’t work out, even though the newsletter portfolios themselves, in aggregate, have been doing fantastic (the yardstick of any fund manager). I highly doubt Mr. Buffett was getting letters in that tough year of ’74 when his business tanked nearly 50%, trailing the market by a considerable margin along the way. The reality is that the customer base, the clientele, the investor, the world, was different back then. It was easier to build relationships. In this, part I of a three-part series discussing Berkshire Hathaway's 2015 annual report, I'll adopt a free-form style in writing an annotated commentary, pulling out excerpts that I’d like to talk about, and adding to areas that I think would be helpful for readers to understand. What you’ll find below in italics is the actual excerpt from the 2015 annual report, and my commentary in regular type. To access the 2015 annual report, as published, please click here. With all of this said, let’s finally begin! By the early 1990s, however, our focus had changed to the outright ownership of businesses, a shift that diminished the relevance of balance-sheet figures. That disconnect occurred because the accounting rules that apply to controlled companies are materially different from those used in valuing marketable securities. The carrying value of the “losers” we own is written down, but “winners” are never revalued upwards. We’ve had experience with both outcomes: I’ve made some dumb purchases, and the amount I paid for the economic goodwill of those companies was later written off, a move that reduced Berkshire’s book value. We’ve also had some winners – a few of them very big – but have not written those up by a penny. Over time, this asymmetrical accounting treatment (with which we agree) necessarily widens the gap between intrinsic value and book value. Today, the large – and growing – unrecorded gains at our “winners” make it clear that Berkshire’s intrinsic value far exceeds its book value. That’s why we would be delighted to repurchase our shares should they sell as low as 120% of book value. At that level, purchases would instantly and meaningfully increase per-share intrinsic value for Berkshire’s continuing shareholders. This excerpt from Mr. Buffett’s letter hints at the irrelevance of using certain items on the balance sheet in the valuation context. The Oracle is not saying the balance sheet itself is not important or not without information value in the valuation context – it certainly is. For one, we know that a company’s net cash or net debt positon on the balance sheet represents one of the most important dynamics of the intrinsic value equation, much like your net worth considers your banking account in the calculation. In this excerpt, the Oracle of Omaha is saying that certain investments are held at cost on the books and never “written up” to their true intrinsic worth. This means that intrinsic value is and will always be calculated differently than what’s provided in the GAAP accounting representation. Said differently, traditional book value or shareholders’ equity is far less important in valuation than evaluating the discounted future enterprise free cash flows of a business that form the backbone of the company’s valuation. Certainly book value and book value multiples have some applications in the banking and insurance industries, particularly within the framework of a residual income model (where book value forms the foundation), but in the cases of valuing operating entities, such as Walmart (WMT) or IBM (IBM) or Precision Castparts, book value is about as close to meaningless as it gets. Operating companies are (should be) valued on the basis of their net cash or net debt positions and the present value of their future enterprise free cash flows. The Oracle is quite the salesman, and what he is saying in the last paragraph of the excerpt is that because of the difference between GAAP “value” representation and how true intrinsic value is calculated, Berkshire Hathaway is worth at least 120% of book value (his opinion). Remember: price is what you pay for something (it’s the stock quote), while value, in the form of a company’s net balance sheet impact and future enterprise free cash flow stream, is what you get. Though Mr. Buffett makes a very reasonable argument, book value should never serve as a valuation anchor for any operating entity, including insurers that hold operating entities like Berkshire Hathaway. In any case, we think Mr. Buffett is using the price-to-book multiple as a way to explain his company’s valuation dynamics, much like an investment banker may use EV/EBITDA to explain a takeout multiple. At the end of the day, however, the proper way to value Berkshire would be a sum of the parts analysis, valuing each business separately and distinctly at a consolidated cost of capital. Nevertheless, at the end of 2015, Berkshire Hathaway’s shareholders’ equity (book value) balance stood at $258.6 billion (page 67) with equivalent B shares outstanding of 2.465 billion, amounting to a book value per share of ~$105. Berkshire’s share price of ~$138.50 at last check means shares are trading at a very healthy 1.32 times book. Not exactly cheap enough for Mr. Buffett to be buying back stock…yet. The most important development at Berkshire during 2015 was not financial, though it led to better earnings. After a poor performance in 2014, our BNSF railroad dramatically improved its service to customers last year. To attain that result, we invested about $5.8 billion during the year in capital expenditures, a sum far and away the record for any American railroad and nearly three times our annual depreciation charge. It was money well spent. Mr. Buffett is talking about the capital intensity of a railroad’s operations in this excerpt. Many railroads are believed to have very strong economic moats, or competitive advantages, and this may be true, but the reality is that their moats arise from hard-to-duplicate assets in the form of existing track. The problem with such track, however, is that it is incredibly capital intensive to maintain, and while railroads generate sufficient free cash flow and have been benefiting from a benign pricing environment, the reality is that the capital outflows associated with their businesses mean economic returns will only be slightly better than the cost of capital. The Oracle has learned quickly just how costly operating a railroad can be, shedding out nearly three times its depreciation charge in 2015 at BNSF. Over the long run, capital spending should approximate depreciation, but the current capital cycle build is tremendous, and we think BNSF will find itself spending more than depreciation for some time. We’re not exactly enthused by the implied free cash flow generation at BNSF for the year; Union Pacific (UNP), for example, generated nearly $2.7 billion in free cash flow, while capex/depreciation stood at 2.3x for the year, and Canadian National (CNI) pulled in $2.4+ billion in free cash flow, while capex/depreciation came in at 2.3x in 2015. As Buffett puts it, “For most American railroads, 2015 was a disappointing year.” … I will be discussing the “Powerhouse Six.” The newcomer will be Precision Castparts Corp. (“PCC”), a business that we purchased a month ago for more than $32 billion of cash. PCC fits perfectly into the Berkshire model and will substantially increase our normalized per-share earning power. Under CEO Mark Donegan, PCC has become the world’s premier supplier of aerospace components (most of them destined to be original equipment, though spares are important to the company as well). Mark’s accomplishments remind me of the magic regularly performed by Jacob Harpaz at IMC, our remarkable Israeli manufacturer of cutting tools. The two men transform very ordinary raw materials into extraordinary products that are used by major manufacturers worldwide. Each is the da Vinci of his craft. PCC’s products, often delivered under multi-year contracts, are key components in most large aircraft. Other industries are served as well by the company’s 30,466 employees, who work out of 162 plants in 13 countries. In building his business, Mark has made many acquisitions and will make more. We look forward to having him deploy Berkshire’s capital. We fell in love with Berkshire all over again when Mr. Buffett announced his intentions to buy Precision Castparts. As many readers are aware, Precision Castparts has been one of our favorite companies of all time, and the aerospace metal parts maker had been a large winner in the portfolio of the Best Ideas Newsletter. It’s a company that I have personally followed for most of my professional career, and having watched CEO Mark Donegan in action, the Oracle’s assessment of his managerial prowess is spot-on. If CEOs approached their businesses in the same capacity and attention-to-efficiency as Donegan has in the many years he has been at the helm, we’d see explosive earnings growth in their operations, too. Though Alcoa (AA) is becoming more and more of a player in high-end precision metal applications, Precision Castparts is exactly what Mr. Buffett says about it: a powerhouse. The company has decades’ long relationships with some of the best engine manufacturers in the business, including General Electric (GE) and its dollar content per aircraft has only increased as the cyclical upswing in commercial aircraft making ensues. Certainly there are some concerns given Boeing’s (BA) recent expectation for commercial deliveries to plateau in 2016, and while some executives have expressed skepticism about the true health of the wide-body market in the face of collapsing jet fuel prices, the team at Precision knows how to drive margins higher during strength and cut costs while things get tough. There may not be a better operator than Precision Castparts. It’s good to see the company become a part of the Berkshire umbrella, and it may be a large part of the reason why we will consider adding Berkshire to the Best Ideas Newsletter portfolio in coming weeks. Congrats! Berkshire’s huge and growing insurance operation again operated at an underwriting profit in 2015 – that makes 13 years in a row – and increased its float. During those years, our float – money that doesn’t belong to us but that we can invest for Berkshire’s benefit – grew from $41 billion to $88 billion. Though neither that gain nor the size of our float is reflected in Berkshire’s earnings, float generates significant investment income because of the assets it allows us to hold. Meanwhile, our underwriting profit totaled $26 billion during the 13-year period, including $1.8 billion earned in 2015. Without a doubt, Berkshire’s largest unrecorded wealth lies in its insurance business. We’ve spent 48 years building this multi-faceted operation, and it can’t be replicated. The insurance business has been the bread-and-butter at Berkshire for decades, and the company’s underwriting prowess and allocation of float have simply been excellent, especially during the past decade or so. Though Buffett says Berkshire has spent nearly 50 years building a “multi-faceted operation, and it can’t be replicated,” the insurance business is largely commoditized – meaning insurers can really only compete on price. When new products are introduced, they can be copied almost immediately by peers. One of the areas where insurers can differentiate, however, is with respect to credit quality and balance sheet strength, and Berkshire’s credit rating of Aa2, stable, speaks to that dynamic. Here’s Moody’s rating rationale from earlier this month, for example: Moody's said that Berkshire's ratings reflect its strong market presence in its principal (re)insurance operations, the diversification of its earnings from both regulated and non-regulated businesses, and its sound balance sheet. The ratings also incorporate the conservative operating and financial principles of the current management team. These strengths are tempered by potential earnings and capital volatility within the (re)insurance operations related to large, concentrated stock investments as well as large individual underwriting transactions. Other challenges for the company include enterprise risk management given the expanding business portfolio, and management succession given the critical role that CEO Warren Buffett has played in developing the culture and financial track record. A few weeks ago, Standard & Poor’s reaffirmed Berkshire Hathaway’s credit ratings at AA, even though the risk for a downgrade had increased following the Precision Castparts purchase. Berkshire holds S&P’s third-highest rating on its system, and its fortress balance sheet means borrowing costs and the “sweet” deals the Oracle has come to know will continue to find their way to his doorstep. In his words, “With the PCC acquisition, Berkshire will own 10 1⁄4 companies that would populate the Fortune 500 if they were stand-alone businesses -- our 27% holding of Kraft Heinz (KHC) is the 1⁄4. That leaves just under 98% of America’s business giants that have yet to call us. Operators are standing by.” |