Member LoginDividend CushionValue Trap |

Stock Returns and Financially-Engineered Dividends

publication date: Dec 27, 2015

|

author/source: Brian Nelson, CFA

“Business owners across the world know that their business is not more or less valuable because they paid themselves a higher distribution/dividend this quarter. In fact, the more they pay themselves in distributions/dividends, the less the franchise is worth.” – Brian Nelson, CFA

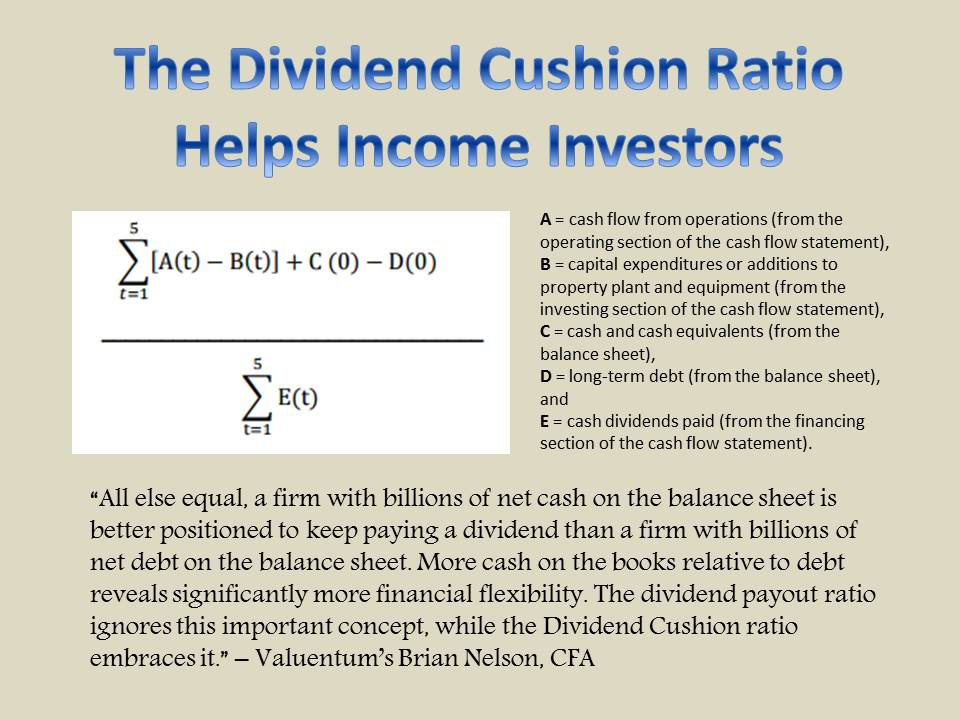

Image Source: Images Money This article seeks to introduce investors to a critical concept often lost on those focused intensely on a company's dividend payout: dividends are not an additive source to total stock returns above and beyond what a company would generate in capital appreciation. Dividends, instead, deduct from the capital appreciation a stock would otherwise have generated in the event that it did not pay a dividend. From what we can tell, this concept is not well understood. For one, widely-circulated research implies that dividends "generate" a large portion of stock returns, and easily-communicated methodologies oversimplify the stock return composition (e.g. dividend yield + earnings + speculative component), arguably misleading investors to believe that a higher dividend payout and yield will augment the total stock return equation. This is simply not true. Stock returns aren't enhanced by a company's dividend yield, no more than an entrepreneur's company is worth more because he or she pays himself or herself a large dividend this holiday season or next. In fact, because the company has less cash on the books as a result of the payment of the dividend, one can say the franchise is worth less (the sources of intrinsic value are discussed later in this article). What is not explained well (and something that we believe should be emphasized) is that the higher the dividend yield of a company, the lower the capital appreciation potential; and the lower the dividend yield, the higher the capital appreciation potential, all else equal. If, for example, a company's total return for a given year is 8% and a company paid a dividend yield of 2% during the year, the company's capital appreciation for the year would be 6% (2%+6%=8%). If the company paid a 4% dividend yield, the company's capital appreciation for the year would be 4% (4%+4%=8%). If it didn't pay a dividend, shares of the company would have advanced 8%. The total return of the company is 8%, regardless of its dividend policy, all else equal. When a company pays a dividend, its intrinsic value is reduced by an amount equal to cash dividends paid (even the stock exchanges reduce the price of the stock by the dividend payment per share when it goes "ex dividend"). Although the proliferation of dividend growth strategies in recent years has arguably enhanced the capital appreciation component of dividend-paying stocks, in aggregate, due to the introduction of a wider audience (more buying) to these particular equities, the core relationship between capital appreciation and dividends has not changed. Let's really hit this concept home by talking about the three primary sources of intrinsic value: the net cash position on the balance sheet, the future enterprise free cash flows a company generates, and any "hidden" assets not captured in those future expected enterprise free cash flows. First, the company’s balance sheet can be a source of value. For example, let's assume a company has $1 billion in total cash and $500 million in total debt. If the board of directors decides to shut down the company, shareholders would be entitled to the net cash position of the firm, or $500 million, adjusted for closing (run-off) expenses. In another example, a company with $1 billion in net cash on the books is worth more than a company with $10 million of net cash on the books, all else equal. The balance sheet matters! The payment of dividends reduces the cash that otherwise could have accumulated on the balance sheet (if it had not been paid), which would have enhanced the value of the company (and by extension, its capital appreciation potential). Perhaps counter-intuitively, paying a distribution or dividend reduces the intrinsic value of the company because it reduces the net cash position on the balance sheet relative to what it otherwise would have been if it didn't pay the distribution/dividend, all else equal. Assuming prices are "tied" to value, prices (and capital appreciation) are reduced as well. Second, the company’s operations generate value, as measured by the present value of all future enterprise free cash flows (FCFF) that are generated to all stakeholders. A company’s low-cost position, its network effect, its brand strength, or any intangible asset can effectively be valued by summing up the firm’s ability to translate those strengths into future enterprise free cash flows. We call this exercise: "quantifying the qualitative assessment." After all, if a company can't translate these "moaty" characteristics into what matters (enterprise free cash flow), then what good are they? Third, a company’s “hidden” assets such as an overfunded pension or an equity stake in another company that is not accurately reflected in GAAP accounting statements have value. There are a large number of companies that have "hidden" assets and perhaps an equally large number of activist investors seeking to encourage executive teams to unlock value from such "hidden" assets. When a company is able to monetize these "hidden" assets, management is said to have "unlocked shareholder value." Most everything else, however, is already captured within the intrinsic value calculation itself (i.e. the three primary sources of intrinsic value: balance sheet net cash, future enterprise free cash flows, "hidden" assets), whether it be the company’s decision to increase its dividend, buy back stock, or pursue any other strategic endeavor. Over time, for example, a company's intrinsic value will increase at the discount rate less the dividend yield, the amount of value a company's buyback program generates or destroys is contingent upon the relationship between a company's share price and its intrinsic value estimate, and future strategic endeavors are captured within estimates of future enterprise free cash flow growth. When one thinks about the concept of intrinsic value in a financial valuation context, as in the case of future enterprise free cash flows, it helps to cut through a lot of the qualitative noise. The only way a company’s dividend policy can theoretically “generate” value, in our view, is if management would have otherwise invested that capital elsewhere in value-destroying businesses (acquisitions) or bought back stock at irrational, overpriced levels. A company’s dividend policy is neither value-creating, nor value-destroying in the case of business (economic) returns, though if management’s dividend policy strains the balance sheet, a higher cost of capital can eventually hurt intrinsic value. This is what we're seeing now in many overleveraged, capital-market-dependent entities whose fundamentals are waning. If the dividend is not a driver behind intrinsic value, but rather a symptom of it (or an output of it), how does one measure what something is worth then? Well, the answer to this question rests in evaluating the three sources of intrinsic value above. Ask these questions, for example: What is the company's net cash position on the balance sheet? What are the enterprise free cash flows the firm is expected to generate in the future? Does the entity have any "hidden" assets, whose value is not captured in those future enterprise free cash flows? The answers to these questions will lead to objectively estimating intrinsic worth. It’s really that rudimentary, and you'll notice these three drivers of intrinsic worth have nothing to do with a company's distribution or dividend. An asset, adjusted for balance sheet considerations, whether it is a house or a car or a stock or an MLP or anything else, cannot be worth more than the discounted future enterprise free cash flows that it generates. A house is worth the discounted rental stream to the owner plus resale price (though many real estate agents may use "comps" as a way to help "price" the property). A car is worth the present value of lease payments to the dealer plus a terminal/scrap value. A stock is worth the net cash on the company's books plus the present value of future enterprise free cash flows, discounted back to today (+/- "hidden" assets). An MLP is valued the same way as that of a corporate -- no matter how investors may want to "price" these business models. Though assets are sold every day at prices that exceed their intrinsic worth (did you sell someone your overpriced stock recently?), and many may still want to believe in what we would describe to be an "invalid" pricing paradigm focused on financially-engineered dividends, it should go without saying that no matter what price you pay for an asset (including stocks), their value is what you end up getting. Price and value, however, are almost never the same, and both are moving targets over time. [Note: we define a financially-engineered dividend as one in which management uses the financing section of the cash flow statement via equity and debt issuance to offset net free cash flow shortfalls, as measured by cash flow from operations less all capital spending, to keep paying a dividend to sustain an artificial equity pricing paradigm surrounding the dividend payment. Not all distributions/dividends are authentic, or organic, in our view.] One of the business models that we spend a lot of time talking about is the MLP structure, but this is an area that we really don’t care much about, unfortunately. We did our very best to save investors a ton of money in the space, warning in advance of the recent unit-price collapse, but for those just joining us, you might not know that the MLP space has never really resonated with our team. We've known for a long time that investors today already own whatever their investment will ever pay them in distributions/dividends in the future, and we'll never be lured into the promise of a higher distribution/dividend payment, when underlying fundamentals of the entity are heading south, especially when the payout is already a multiple of free cash flow or earnings. This is sometimes a difficult concept for new investors to understand. Often is the case that the company’s higher dividend yield reflects greater risk with respect to the sustainability of the stock's distribution/dividend and the company’s business model than anything else. Investors already own via the stock price whatever future distributions/dividends (and the growth in them) a company will ever pay to them (it's already in there, and paying the distribution/dividend reduces the unit/stock price). Though far from a perfect indicator, raising the dividend is but a symptom of management's expectations for improving future enterprise free cash flow generation, assuming the distribution/dividend is organically-derived -- meaning it is a portion (a subset) of enterprise free cash flow. Because the dividend itself is not a driver behind future enterprise free cash flow generation (it is paid from it), it therefore cannot be a driver behind intrinsic value. In the event equity prices are not "wrongly" set on artificial pricing paradigms based on financially engineered payouts that are a multiple of organically derived free cash flow and earnings, stock prices should (and do) inevitably follow the enterprise free cash flow valuation estimate of the equity, though various estimates exist. On the other hand, entities that are "priced" on financially-engineered payouts have a significantly higher chance of witnessing their unit prices collapse. Without a doubt, a company’s dividend policy can create excitement around its stock price, particularly with interest rates so low, but the financial engineering of lofty dividend payments is an impermanent phenomenon that, in our view, will eventually come back to bite companies engaged in such activities. Many of these "types of companies" have already succumbed to the ballast of their overleveraged balance sheets and their artificial dividend payments, and we think it's only the beginning as the credit cycle matures. Two things to remember: the dividend yield is not additive to stock returns and not all dividends are created equal! Be well and happy holidays! |