Member LoginDividend CushionValue Trap |

The Real Reason Why Moats Matter

publication date: Mar 27, 2023

|

author/source: Valuentum Editorial Staff

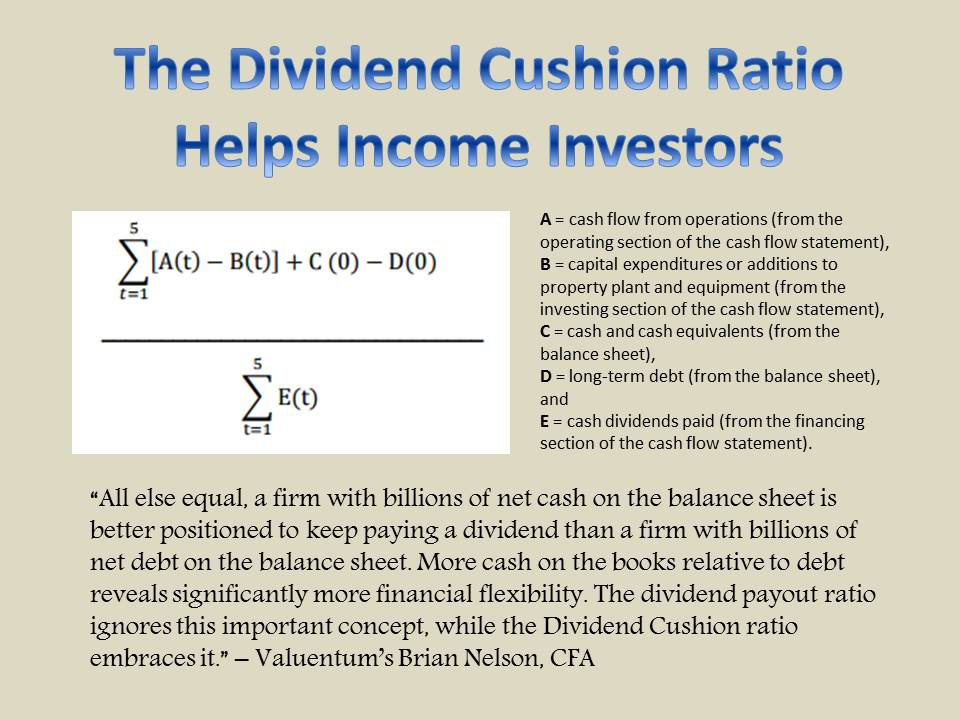

Image Source: Ray in Manila Valuentum: We’re here today with Valuentum's President of Investment Research Brian Nelson to talk about the concept of an economic moat. You think the concept of an economic moat is one of the most misunderstood topics in finance. Can you elaborate? Nelson: Sure, of course. An economic moat was first coined by the Oracle of Omaha, Warren Buffett, to describe significant and sustainable competitive advantages. Now, if you ask any business, they’re going to tell you that they have an economic moat of some sort, whether it’s some low-cost position or intangible asset or an impenetrable network effect. Investors today are at a disadvantage of misinformation given just how widespread the term moat or competitive advantage has become. It’s thrown around everywhere across research firms and even at the frameworks of buy-side shops across the globe, fairly or unfairly. To a large degree, the term has become a commodity. The problem is that there is no standard definition of an economic moat, and no one has a monopoly on the opinion of what comprises a true competitive advantage. So, to us, the concept is very opaque, undefined, and doesn’t tell us much about the true, intrinsic worth of a company. Valuentum: Fascinating. So, do you think Buffett is wrong about liking companies with moats? What gives? Nelson: Absolutely not. Buffett likes companies with sustainable competitive advantages, in his view, but he also likes companies that generate significant returns on invested capital, have excellent management teams, and possess solid capital-allocation plans. Importantly, however, Buffett likes to scoop up great companies at a bargain, using the concept of a margin of safety. He also likes great companies at fair prices, too, but the point is that the area of valuation and using a margin of safety is far more important than a very subjective and qualitative moat assessment. Whether someone says a company has a wide moat or a very small moat shouldn't matter as much as whether a great company can be purchased for fifty cents on the dollar. Valuentum: Why do you think that? Nelson: Well, the reality is that any asset – whether it’s a company, a stock of the company, a rental house, a rental car, or even a bed and breakfast – is worth the present value of its future expected free cash flows. I think where investors get confused is that they believe the moat concept influences these future free cash flows in such a way that the passing of time makes a moaty company more valuable than a non-moaty company. This is just not true. The reality of the situation is that over time the value of a stock is generally going to increase on an annual basis by its respective discount rate (weighted average cost of capital) less its dividend yield, assuming future forecasts are accurate. This is a law of valuation. It doesn’t matter if the stock has a significant competitive advantage or not--such an assessment is already embedded in the future expected free cash flows. Valuentum: This seems confusing. Are you saying that moats don’t matter? Nelson: No, not all. Let’s try this to illustrate what I'm saying. If an investor, for example, values a no-moat company and a wide-moat company, the present value of those cash flows has already been defined in the valuation process, meaning the investor has already identified the future free cash flows of the business that would result either from a firm’s no-moat operations or from its moaty operations. A subjective assessment of its competitive advantages has already influenced that future expected cash-flow stream. If those forecasts are then accurate, a firm is going to generate that cash-flow stream on the basis of its competitive advantages, and therefore, a firm’s value is going to generally increase on an annual basis by its discount rate (weighted average cost of capital) less the dividend yield. This will happen whether the company is a no-moat equity or a wide moat equity. Surely, a moaty company may be able to compound cash flows better in the future than a no-moat company can (or generate significantly more cash flow than a no-moat company does), but this dynamic is already reflected in the cash flow forecasts, and by extension, it has already been captured in the moaty firm’s fair value estimate. Valuentum: Interesting. Would this then lead investors to believe that firms with no moats outperform firms with wide moats since they have higher discount rates within the valuation process because of their higher-risk profiles? Nelson: Yes, at times. Empirical evidence has shown through the course of the economic cycle that companies with no-moats have generally outperformed firms with wide moats. For example, undervalued, no-moat firms have performed as well as undervalued wide-moat firms over the 10-year period ending 2012, while no-moat firms that weren’t undervalued exceeded the performance of wide-moat stocks in the remaining three of the four valuation buckets that were studied (Source: Miller, 1/1/2013, Morningstar). Valuentum: Hmmm....why not just buy a basket of risky, no-moat stocks then? Nelson: Well, that’s a fascinating question. The American Association of Individual Investors (AAII) runs a Model Shadow Stock Portfolio that is focused on relatively small companies, firms with market capitalizations less than $300 million. Most firms in this category haven’t yet developed what I would describe to be a sustainable competitive advantage, or any sort of moat, so I’d assess the portfolio as largely a no-moat portfolio. Yet, the cumulative return of this strategy has been remarkable. This strong performance of no-moat stocks is driven more by the context of valuation as opposed to any competitive-advantage assessment, in my view. The value of higher risk stocks, by definition, will advance at a higher annual pace than lower-risk stocks over time, all else equal (they have higher discount rates in a discounted cash-flow process to reflect their heightened risk profile – think risk premium). But there’s also another dynamic at play here. As markets remain benign, riskier stocks are re-priced higher using lower discount rates (credit availability is improved). The longer duration cash-flow profile of higher-risk, no-moat companies is then magnified when the cost of borrowing is reduced. This makes no-moat firms very volatile through the credit cycle, but it also is responsible for their significant outperformance during good times. Moaty stocks, on the other hand, are less impacted by credit availability, and therefore, their discount rate and intrinsic value does not experience much volatility. Valuentum: Do you think investors are placing too much emphasis on a company’s moat then? Nelson: It all depends. For new investors, starting with evaluating a company's economic moat, or competitive advantages, is a great way to avoid huge financial missteps like betting on cryptocurrencies, for example, but for experienced investors, whether one believes a company has a big, small, or huge moat becomes a rather subjective assessment--and one already factored into the valuation (and share prices). After all, a dollar from a no-moat firm is worth a dollar from a moaty firm. A dollar from a no-moat firm 10 years from now may be worth less than a dollar from a moaty firm 10 years from now due to the higher discount rate, but this is already largely captured in the valuation process today. The long run, or the time horizon that a moat considers, is already captured in the value of the company today. Valuentum: Just to clarify, moats are important because they drive an assessment of a company's future expected free cash flows, and therefore are already fully captured in a company’s valuation--making the qualitative discussion of the moat a moot point. Nelson: Yes, I think that is fair. An evaluation of a company's moat, or a competitive advantage assessment, is generally a very important consideration in arriving at the estimate of future free cash flows. The discounted future free cash flows, however, roll up into the underlying valuation--and the underlying value of a stock advances at the discount rate (weighted average cost of capital) less the dividend yield (assuming the forecasts are accurate) in each respective case. The moat is not separate than valuation, but rather it is already embedded within it. Valuentum: Fascinating. If a moat is already embedded in valuation, why does one pay attention to it at all? Nelson: Well, I think it comes down to 1) assessing the risk tolerance of the investor and 2) the risk to the future free cash flows. For one, most investors cannot sleep at night if their portfolio experiences wild swings, and moaty stocks, by definition, should be less volatile through the course of the credit cycle than no-moat stocks. Investors generally accept lower volatility for lower returns over certain market cycles. As empirical research has concluded in certain studies, wide moat stocks tend to underperform no-moat stocks across almost every valuation bucket. Second, as it relates to the risk to the valuation of the equity, moaty stocks tend to have more predictable future expected free cash flows and more reliable valuations. This offers greater confidence that their future expected free cash flows will be achieved. However, the greater predictability is why such moaty stocks have a lower discount rate in the valuation process, and this results in a comparatively lower value-advance over time than companies with higher discount rates that don't pay dividends, or entities of the no-moat variety. Valuentum: Things seem to be getting a bit counterintuitive, so I'll ask something that probably doesn't make much sense for a first-level thinker, but here goes: Why not buy stocks with the worst fundamental qualities if empirically they are set to do better? Nelson: Well, that’d be a foolish move. We can’t forget about individual bankruptcy risk and the potential evaporation of equity in higher-risk small and micro caps that may occur under tightening credit cycles. That said, investors may do well with a basket of no-moat stocks over the long run (think of the area of small cap value prior to the dawn of the Internet age), but without broad diversification across firm-specific risk, an individual investor can be harmed should any particular no-moat equity fail – that is, if a firm declares bankruptcy. A concentrated portfolio of fundamentally poor companies is simply a bad idea, in my view. Valuentum: That makes sense. So basically, to cut through everything you said, it comes down to finding undervalued stocks that may have heavily discounted free cash flows? Nelson: In part, but I may add a few things. I think focusing on valuation, and the cash-based sources of intrinsic value in particular, may be far more important than moat labels, by itself, but these dynamics go hand in hand. For example, entities such as Apple (AAPL) and Microsoft (MSFT) have tremendous cash-based sources of intrinsic value -- net cash on the balance sheet and future expected free cash flows -- but they also have extremely wide moats. This is partly why we like large cap growth and big cap tech, more generally. For starters, these areas have strong net cash positions on the balance sheets, while their future expected free cash flows may be heavily discounted in the event that they surprise to the upside, where upward revisions are necessary. Unlike net-debt heavy entities that pay out lots of dividends, the capital appreciation potential for large cap growth and big cap tech is much, much greater, almost by default. Valuentum: Okay you lost me. First, you say that you think no-moat companies should have the greatest value-increases over time because they are riskier, and now you're saying you like large cap growth, which are among the strongest, moat-iest companies out there? Nelson: It's confusing. Let me explain. What investors are after is highly discounted future expected free cash flows, with perhaps an asymmetric upside-potential boost in the event such companies have net-cash-rich balance sheets, too (bankruptcy risk is practically nil). You can find heavily discounted free cash flows in no-moat equities due to their higher discount rates, by definition, but you can also find heavily discounted future free cash flows in established entities that may surprise to the upside. In the first case, in say for no-moat companies, the value-advance occurs in the discounting mechanism within the discounted cash-flow (enterprise valuation) framework, while in the other case, the value-advance occurs in the revisions to future expected free cash flows as time passes. What I like today is betting on long-term upward revisions to future expected free cash flows in the areas of large cap growth and big cap tech. Valuentum: But why? Nelson: Well, because many of these companies aren't weighed down by bloated balance sheets and dividend obligations, their valuations and stock prices have explosive upside potential, something that was on display during 2021, and something that I think we will see again this decade. While the valuations of net-debt heavy, dividend payers may always be relatively grounded, it's not hard to envision a scenario where the market once again builds in strong future expected free cash flows among large cap growth and big cap tech equities in the not-too-distant future. My bet is that future expected free cash flows for large cap growth and big cap tech equities will be revised substantially higher through the course of this decade, and this bet seems like a much stronger one than counting on a bigger value-advance of no-moat equities over time. Valuentum: I see what you're saying. Investors in no-moat small caps, for example, are making a bet on the riskiness of the equities, themselves, trying to capture that bigger value-advance over time, while investors in large cap growth and big cap tech are instead betting on future upward revisions to future expected free cash flows. Nelson: That's a fair way of putting it. The strong business models and cash-based sources of intrinsic value in the areas of large cap growth and big cap tech are hard to bet against, in my view, and I've never been a fan of betting on risky companies just because they are riskier either. Valuentum: Thanks for joining us today. Nelson: Thanks for having me. NOW READ: Economic Moats Matter Less Than a Stock's Valuation (pdf) ---------- About the author: Brian Nelson is the president of equity research and ETF analysis at Valuentum Securities. Brian is frequently quoted in the media and has been a frequent guest on Nightly Business Report, Bloomberg TV, CNBC, and the MoneyShow. Prior to Valuentum, Mr. Nelson worked as a director at Morningstar, where he was responsible for training and methodology development within the firm's equity and credit research department. Brian led the charge in developing Morningstar's issuer credit ratings, developing and rolling-out one of the firm's proprietary credit metrics, the Cash Flow Cushion. Mr. Nelson is very experienced in valuing equities, developing Morningstar's discounted cash-flow model used to derive the fair value estimates for Morningstar’s entire equity coverage universe. Prior to that position, he served as a senior industrials securities analyst covering aerospace, airlines, construction, and environmental services companies. Before joining Morningstar in 2006, Mr. Nelson worked for a small capitalization fund covering a variety of sectors for an aggressive growth investment management firm in Chicago. Brian worked on a small cap fund and a micro-cap fund that were ranked within the top 10th percentile and top 1st percentile within the Small Cap Lipper Growth Universe, respectively, in 2005. Mr. Nelson holds an MBA from the University of Chicago Booth School of Business and also has the Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) designation. Brian can be reached at brian@valuentum.com. ---------- It's Here!

The Second Edition of Value Trap! Order today!

-----

A version of this article appeared on our website April 24, 2014. This article is a thought piece and should not be construed as investment advice. Neither Brian Nelson nor Valuentum are registered financial advisors. Valuentum is an investment research publishing company. Brian Nelson owns shares in SPY, SCHG, QQQ, DIA, VOT, BITO, RSP, and IWM. Valuentum owns SPY, SCHG, QQQ, VOO, and DIA. Brian Nelson's household owns shares in HON, DIS, HAS, NKE, DIA, and RSP. Some of the securities written about in this article may be included in Valuentum's simulated newsletter portfolios. Contact Valuentum for more information about its editorial policies. Valuentum members have access to our 16-page stock reports, Valuentum Buying Index ratings, Dividend Cushion ratios, fair value estimates and ranges, dividend reports and more. Not a member? Subscribe today. The first 14 days are free. ---------- Related Firms - AAII: ALG, AOSL, CSS, DCO, EBF, FVE, FLXS, HDNG, HOFT, ISH, KTCC, KBALB, LMIA, MRLN, MDCI, MIND, ZEUS, PCCC, PCMI, RCMT, REGI, REX, RCKY, SGMA, SALM, SCVL, SMP, TA, VOXX, WLFC Related Firms - wide moat: EXC, SLB, CLB, CHRW, SE, NOV, BAX, KO, PM, IBM, GE, BEN, PG, BRK.A, BRK.B, SYY, EXPD, BLK, EBAY, WU, ESRX Related Firms: MORN, MOAT |

0 Comments Posted Leave a comment