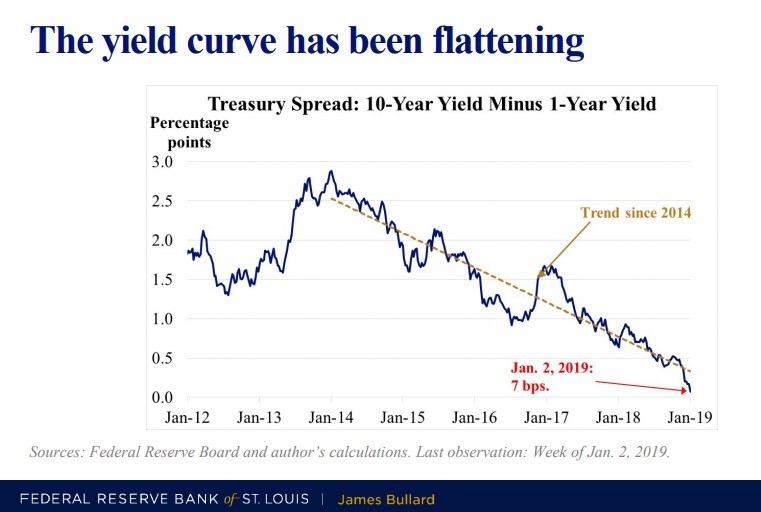

Image shown: The yield curve is flattening. Source: Federal Reserve Bank, St. Louis.

The biggest question with Fed policy is whether the FOMC will purposefully cause an inversion in the yield curve. If it thinks the market is manipulating long rates to influence its policy, it may very well go forward with rate hikes. If it doesn’t, it may very well slow the pace of rate hikes or even pause them. The behavioral implications of a yield-curve inversion may be more significant than the inversion, itself, however.

No Changes to Simulated Newsletter portfolios

Brian Nelson, CFA

On January 10, President and CEO of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, James Bullard offered a number of perspectives on 2019 monetary policy. You can download his slide deck here (pdf). Bullard predicts that inflation will come in on the “low side” of expectations in 2019, viewing this as a signal that “US monetary policy may be overly hawkish (too aggressive in raising rates).” He also believes that “the prospect for a further global growth slowdown is tangible,” and notes the “bearish signal” an inverted yield curve may send.

At Valuentum, we monitor economic activity and monetary policy to assess important variables within our valuation infrastructure. For example, long-term views regarding the rate of economic expansion impact growth rates that we assume in the latter stages of our valuation model, and the risk-free rate is a key variable in determining the discount rate that we use to bring future free cash flows back to today’s value, generally through an estimate of the 10-year Treasury rate. Without a doubt, the global economy and monetary policy play a role in the work we do, but we like to pay the greatest attention to underlying fundamentals of individual companies.

That said, there was one page in Bullard’s slide deck (see image above) that has me thinking the Fed may start to slow rate hikes, and that has to do with the yield curve. Essentially, an inverted yield curve means that there is a disconnect between the Fed’s expectations of inflation and growth and the market’s, and as many know, inversions have been connected to economic recessions through much of the post-World War II era. Of all the reasons to slow Fed hikes, whether it be threats of a China slowdown or other, a purposefully (and large) inversion of the yield curve driven by FOMC action doesn’t seem very likely.

It’s not so much that either the Fed or the market is “correct,” but the behavioral implications from the inversion may be more material to the Fed’s decision-making process than the inversion itself. For example, if investors think an inverted yield curve is associated with a recession, they may sell their stocks and save more in advance of what they think will be a recession, and these actions may actually cause a recession. In my view, while a yield curve inversion suggests less-desirable long-term conditions than short-term ones, an inverted yield curve actually causing the behavior that drives a recession is what may be the biggest concern of all.

The Treasury spread of the 10-year yield minus the 1-year yield stood at 7 basis points on January 2, and Bullard notes that “various measures are all trending toward inversion,” including the 5-year/2-year and the Fed near-term forward. Bullard’s conclusion seems logical and sound to me: “Market based signals such as low market-based inflation expectations and a threatening yield curve inversion suggest that this window of opportunity has now closed.” Bullard seems to think that the Fed hikes during the past couple years are adequate to “contain upside inflation risk.”

We’ll have to wait and see what the Fed has in store for 2019, but we don’t think it is likely it will purposefully drive a significantly inverted yield curve, unless of course it thinks the market is manipulating long-term rates in an effort to influence Fed policy. If it holds that opinion (and it might), then more rate hikes can be expected (regardless of the impact on the yield curve). Inflation expectations appear benign, economic growth remains resilient, the jobs numbers are good, and the unemployment rate certainly isn’t bad. Still, the Fed must know that it may only take the idea of an inverted yield curve, itself, to actually cause the next recession, and that’s definitely something it doesn’t want. All told, the Fed has a lot to think about during 2019, and that it is forced with such a dilemma at 2%-3% short-term rates and not at 6%-7% speaks of just how fragile the global economy may very well be.

The US government shutdown seems to be grabbing most of the headlines recently, but these types of political events tend to be transient in nature with little impact on overall market valuation. The Trump administration noted that the shutdown hurts economic growth by 0.1% every week or so, but J.P Morgan (JPM) CEO Jamie Dimon offered up the view that economic growth in the US could be reduced to zero, giving more credibility to reports of a more outsize impact on the pace of economic expansion in the US as a result of the shutdown. In any case, we believe the US government shutdown, while avoidable and an “unforced error” when it comes to the economy, will be contained to a one-time impact. At the moment, we’re not reading too much into it.

As I write this note, first-quarter 2019 bank earnings are in full swing. In Value Trap, I write how bank valuations are significantly more art than science, given the implicit backing of the US government, and while the first-quarter 2019 reports from Citigroup (C), J.P. Morgan, and Wells Fargo (WFC) weren’t terrible, they weren’t good enough to get us off the sidelines to jump into banking-related entities. If we were to ever put a banking “trade” back on, it would be with the diversified banking ETF, either the Financial Select Sector SPDR (XLF) or the SPDR S&P Bank ETF (KBE). We like the diversification afforded by these ETFs, given the outsize risks any one banking entity may pose given the opaqueness of their books. If the yield curve does significantly invert, we would expect the banking sector to feel the brunt of the pain as lending spreads tighten, though their fee-based business models are much more resilient than in decades past.

When it comes to banking and insurance exposure, we think Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A, BRK.B) represents the better, “safer” idea. Berkshire is one of the top “weightings” in the simulated Best Ideas Newsletter portfolio. In Value Trap, I talk about how Berkshire’s chief Warren Buffett has been there to bail out Long-Term Capital Management (a failed quantitative hedge fund from the late 1990s), how his resources were tapped to tame the Financial Crisis, and how his methods are sound and reliable. More recently, Buffett has made a few missteps, but we think those that learn his ways are wise. I talk a lot about Buffett’s teachings in Value Trap (order paperback on Amazon here), and I hope that you will take a read of the text when you have time.

Tickerized for holdings of the Financial Select Sector SPDR ETF (XLF) and the SPDR S&P Bank ETF (KBE)

—–

Valuentum members have access to our 16-page stock reports, Valuentum Buying Index ratings, Dividend Cushion ratios, fair value estimates and ranges, dividend reports and more. Not a member? Subscribe today. The first 14 days are free.

Brian Nelson does not own shares in any of the securities mentioned above. Some of the companies written about in this article may be included in Valuentum’s simulated newsletter portfolios. Contact Valuentum for more information about its editorial policies.