Let’s talk about index investing, market valuations, and mention how a few ideas in the Best Ideas Newsletter are doing.

By Brian Nelson, CFA

For most investors during most parts of the economic cycle, index investing (VOO), or holding a broad basket of stocks that approximate the returns of a large market index may make a lot of sense. I have always said this from the very beginning: Individual stock selection is not for everyone. What may not be well-known, however, is that index funds have experienced multi-year periods of both outperformance and underperformance relative to actively-managed funds since the dawning of the very first index fund many decades ago. I’m worried that some investors today may not have this complete story in light of some of the news headlines I have been reading.

What is being widely-disseminated in the news is that the past several years have been quite favorable to those preferring a “passive” approach and relatively less favorable to those seeking a more-active bent. One of the biggest behavioral, or cognitive, pitfalls investors sometimes face, however, is something called recency bias, generally defined as when individuals evaluate the most recent trends to determine what may immediately lie ahead. A big trend in the financial industry, if not the biggest trend, has been the massive flow of funds into “passive” products and out of actively-managed vehicles. This has occurred as a result of a number of factors, with one of them being, of course, the recent underperformance of many active managers relative to index funds.

The move to passive shows no signs of slowing either, and passive products aren’t really passive, but that is a topic for another day (i.e. someone manages the index). One may posit, however, that most of the recent underperformance from the actively-managed camp has largely been a result of active managers heeding caution and being prudent in today’s frothy market, perhaps steering clear of speculative entities that have largely been leading the broader market higher, stocks such as Netflix (NFLX) or Tesla (TSLA), for example. Are we to blame these active managers for their prudence or instead applaud them? Are we to reward indexers for their aggressive risk-taking or instead take note of indexing’s potential vulnerabilities near market tops? It’s certainly debatable, but that’s really not what I am getting with this piece.

What I think is most important for readers to remember is that index funds can and have experienced prolonged periods of both outperformance and underperformance. I was recently reminded of a USA Today article from April 16, 2007 (“Great minds don’t think alike about index funds,” John Waggoner), where John Bogle, founder of the Vanguard Group, openly admitted that over the first five-year period since index funds existed, they “were outperformed by two-thirds of funds.” This is the same type of randomness that we are seeing today, but reversed: index funds have outperformed most active managers, after fees, more recently. However, not many in the business seem to be presenting such information in a fair and balanced way, and there may arise a big problem when the loudest and most influential voices are saying that beating the market is not possible. Not possible? It certainly is possible, and over multi-year periods, and right from the words of Vanguard’s founder himself.

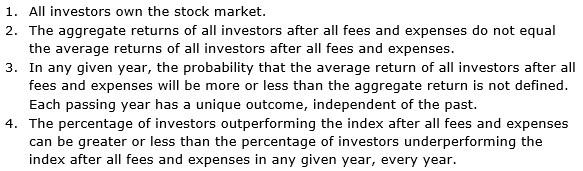

Investors simply deserve the unbiased truth. As an independent publisher, we’re in a unique position to provide such a thing. It will never be up to me to determine what is the best investment path for anybody, but I feel that it is my responsibility that if ‘everyone’ is repeating a fallacy, I must stand up and speak the truth. I view it as my job. Indexing is not a guaranteed way to retirement freedom, no matter what the past suggests. Index funds can be outperformed by actively-managed funds for sustained periods of time, no matter what anybody says. John Bogle’s syllogism that says all active managers underperform index funds after fees is not a correct syllogism of the market, in my view. Here is what I believe to be the correct syllogism that represents the market (I have built a proof, too, to support it). Frankly, I think this is a big deal. Investors and financial advisors all over the planet deserve to know these things, whether they like indexing or not.

Image shown: Nelson’s Syllogism of the Stock Market

But why do I care about a growing portion of the population that is parking their hard-earned money in index funds? To know why, you have to understand how I view index funds, in general. To me, and again, index funds can be the right path for many investors, but to me, they represent “buying everything at any price and holding no matter what,” akin to using the rear-view mirror to drive a car with your hands off the wheel. But why do I care so much, and why now? Well, first of all, because the stock market today is trading at very lofty levels relative to historical measures, something we talked extensively about in the June 2017 edition of the Best Ideas Newsletter.

What I am most concerned about is that recency bias may lead investors to believe today that index funds are guaranteed to outperform actively-managed funds going forward, perhaps like active managers may have believed they’d outperform index funds going forward after their successful five-year stint following the launch of the first index fund many moons ago. My position will never be pro-active or pro-passive, but right down the middle, straight down the middle. My position is pro-truth, pro-investors and standing up for logical reasoning. Bottom line: I don’t want you to be fooled by randomness, and especially I don’t want you to be fooled by randomness in today’s frothy market, where stocks are trading at elevated multiples. Even the Federal Reserve is chiming in about valuations and the “buildup of risks to financial stability.” From their minutes, June 13-14, 2017:

Corporate earnings growth had been robust; nevertheless, in the assessment of a few participants, equity prices were high when judged against standard valuation measures. Longer-term Treasury yields had declined since earlier in the year and remained low. Participants offered various explanations for low bond yields, including the prospect of sluggish longer-term economic growth as well as the elevated level of the Federal Reserve’s longer-term asset holdings. Some participants suggested that increased risk tolerance among investors might be contributing to elevated asset prices more broadly; a few participants expressed concern that subdued market volatility, coupled with a low equity premium, could lead to a buildup of risks to financial stability.

In many ways, our prediction for the stock market “bubble” to continue to inflate in 2017 remains spot on, with major indices setting new highs recently. Our prognostication that President Donald Trump would “trumpet” the market is also coming to fruition, with him tweeting more frequently about record-setting performance in the indices. Here is his latest tweet from July 12: “Stock market hits another high with spirit and enthusiasm so positive. Jobs outlook looking very good! #MAGA.” I love that the President is paying attention to the stock market and the wealth of Americans, and I hope that he may even tweet about the risks of stock market investing, too. For one, past results are never a guarantee of future performance, and this applies to indexing, too. Second, I think the financial industry needs an overhaul. I think we need to redefine what cost means to the investor. It goes far beyond the fund expense ratio and should include the price of the underlying constituents of the fund, too. A fund with a 0.00001% expense ratio where its collective holdings are trading at 100000x earnings, for example, certainly can’t be considered “low cost,” can it?

As it relates to broad-based market valuations, the forward 12-month P/E ratio of the S&P 500 is 17.3 times, as of July 7, according to FactSet, above the 5-year average (15.3) and the 10-year average (14)–meaning the market continues to trade well above historical valuation norms. The cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio, the market-cap-to-GDP ratio, and anecdotal evidence surrounding the performance of ultra-speculative vehicles further support the view that we are in an overheated market. In some ways, what has made index investing look so good the past few years is that many reasonable investors may have taken profits off the table due to valuation concerns. By blindly holding some of the most overheated stocks as they become even more “bubbly,” indexers may be championing risk more than anything else. I firmly believe that if I were not warning investors about the random outcomes of indexing relative to active management and the frothiness of today’s stock market, I wouldn’t be doing my job. What are other publishers doing, I say?

One more thing about indexing. According to Bank of America, “the proportion of stocks on the main U.S. benchmark equity index now managed passively has nearly doubled since the 2008 crisis to 37 percent while ETF trading accounts for about a quarter of the daily volume across U.S. exchanges.” That’s a staggering statistic. More than one third of capital in the S&P 500 (SPY) is passively-managed (and this has nearly doubled since 2008), meaning that a large and growing part of the market is not paying attention to the price-versus-fair value equation or even working to set stock prices efficiently, particularly if such passive money is long-term oriented (“buy and hold”). I posit that if quantitative investors and algorithmic traders are basing their systems on today’s market where more than one third aren’t paying attention to the price (or cost) of their investments, then the price-setting mechanism of the market may be starting to break down. Remember, index investors still impact the market price with their buying and selling activity. They are not bystanders, but market participants. I think the proliferation of indexing coupled with quantitative models that incorporate indexing’s real impact, by definition, pose a meaningful, systematic risk to the health of the stock market.

As we’ve been saying for some time, however, even as we grow more and more concerned about the stock market, the Best Ideas Newsletter portfolio still has a large number of ideas within it. Many of them have been performing fantastically as of late, too, namely Facebook (FB) and PayPal (PYPL), which have set new highs recently. Top-weighted Visa (V) is trading north of the mid-$90s, and many other ideas have been doing equally well. We continue to be pleased with our value processes at Valuentum (the discounted cash-flow model), but if it weren’t for our methodology that lets “winners” run, many ideas in the newsletter portfolio would have been discarded some time ago. We’ve stated many a time before that value investors can sometimes truncate performance when they sell a stock at “fair value.” The Valuentum methodology generally requires a stock to be both overvalued and exhibiting poor technical and momentum indicators before it is removed from the Best Ideas Newsletter portfolio. As author of “A Random Walk Down Wall Street” and indexing proponent, Burton Malkiel, has more recently embraced, “Malkiel Balks, Yellen Talks,” combining value and momentum can have tremendous benefits. This is something we’ve been saying for years.

I hope you enjoy the July edition of the Best Ideas Newsletter!

<newsletter to be released July 15, 2017>

Tickerized for ETF coverage.