Image Source: Chevron Corporation – November 2019 IR Presentation

Summary

In this note, let’s cover the current state of raw energy resource prices in North America and around the world.

We’ll analyze Chevron’s 2020 capital investment and exploration budget, in particular, and the global energy industry at-large.

Shares of CVX appear generously valued as of this writing given the numerous headwinds facing the energy industry going forward.

By Callum Turcan

The world of oil and gas equities has been battling with persistently low raw energy resource prices for some time now. Back in the middle of 2014, a barrel of light sweet crude delivered to Cushing, Oklahoma (home of the West Texas Intermediate, or WTI, benchmark), would fetch over $100. Now you would be lucky to get $60, and furthermore, please note that the WTI futures curve is in backwardation. That means spot prices are trading above the price of future deliveries which is indicative of various things including: 1) expectations of relatively weaker supply/demand dynamics in the medium term (i.e. non-OPEC supply growth combined with a cooling of the Chinese economy leading to rising expectations for material crude storage builds worldwide), and 2) concerns that the ongoing OPEC+ supply curtailment agreement (which was recently extended into March 2020) will eventually end, among other factors.

Additionally, please note that natural gas prices in both the US and abroad are also quite low, relatively speaking. Henry Hub, the US benchmark for natural gas prices (based on deliveries to Erath, Louisiana), has been trading below $3 per million British thermal units (‘MMBtu’) outside of periods of demand shock (i.e. winter storms) since 2014. Prices easily topped $6 per MMBtu during the second half of the 2000s decade, before the fracking boom really took off during the start of the 2010s decade.

When it comes to liquified natural gas (‘LNG’), prices have tanked from over $10 per MMBtu a few years ago to $5.50 per MMBtu as of late-2019 (based on Japanese deliveries). That has made exporting LNG a less attractive endeavor, especially when considering additional supply set to come online from the US, Canada, Qatar, Russia, and Australia over the coming years. Additionally, please note that many LNG supply contracts are based off of Brent-linked pricing (Brent, the international oil pricing benchmark, trades at a modest premium to WTI as of this writing but pricing is still lackluster relatively speaking). While this dynamic is changing and some LNG supply contracts are now based off Henry Hub pricing, it’s a slow process.

Please keep this information in mind as we segue to our next topic, and that’s Chevron Corp (CVX). Shares of CVX yield 4.1% as of this writing and are trading at the upper end of our fair value estimate range.

Chevron’s 2020 Strategy

Chevron announced its organic capital and exploratory spending program budget on December 10. The energy giant plans to spend $20.0 billion next year with an eye towards the Permian Basin (Chevron is betting the barn on this unconventional play), Kazakhstan (Chevron has economic interests in massive oilfields in the country), and the US Gulf of Mexico (particularly deepwater projects). That’s in-line with what Chevron expects to spend on organic capital investment and exploration spending this year, and please note that expected capital expenditures made by affiliate companies (largely Chevron’s Kazakhstan venture) are very material (affiliate company capital investment and exploration spend is estimated at $6.3 billion in 2019 and $6.2 billion in 2020).

Permian Basin

By 2023, Chevron aims to produce 900,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day (‘BOE/d’) from its unconventional Permian operations in West Texas and Southeastern New Mexico. That’s on top of its decent conventional production base in the region. Management allocated $3.6 billion from Chevron’s capital investment and exploration budget to the firm’s upstream unconventional Permian development activities in 2019, which will rise to $4.0 billion in 2020.

Chevron over the past century (through various companies that eventually become the energy giant we know today) built up an enormous acreage leasehold and mineral rights position in the Permian, which before the fracking boom was considered to be a very sleepy area for oil and gas development activity. At the end of 2018, Chevron owned the leasehold on ~500,000 net acres in the Midland sub-basin and ~1,200,000 net acres in the Delaware sub-basin within the Permian Basin that were considered prospective for unconventional plays, on top of additional leaseholds in the nearby area that are considered prospective for conventional opportunities.

Upstream well economics are supported by Chevron owning the mineral rights across an enormous part of its leasehold position, with ~80% of its Permian leasehold possessing no or low royalties. Royalties can range from 7%-15% of wellhead revenue depending on the agreement, without the mineral rights owner having to put up anything in terms of covering well development costs and ongoing operating expenses. This advantage over its smaller upstream-only peers can’t be understated as Chevron is keeping a much larger slice of the total gross revenue stream (production taxes, royalties, and similar factors are extremely important here in an industry with high operating leverage).

In 2018, Chevron’s unconventional net Permian production averaged 159,000 barrels per day of crude oil, 66,000 barrels per day of natural gas liquids, and 501 million cubic feet per day of natural gas. Using a 20:1 conversion ratio for its natural gas production (6 million cubic feet to 1 barrel of oil equivalent is the industry standard, however, due to US prices being so low, using the 20:1 ratio provides for a better comparison when also taking international operations into account and is used by numerous financial analysts), Chevron’s unconventional Permian Basin output clocked in at ~250,000 BOE/d in 2018 (or ~310,000 BOE/d under the 6:1 conversion ratio). That production base is expected to roughly triple by the early-to-mid-2020s assuming current guidance is achieved.

Chevron purchased a small refinery from Petrobras (PBR) earlier in 2019 for $350 million before working capital considerations to support this growth trajectory. The Pasadena refinery in Texas has the capacity to refine 110,000 barrels of light crude per day, the kind of crude that’s produced at unconventional oilfields all across the US. There’s a very high likelihood that Chevron will expand the capacity of that refinery in the medium term. Management allocated $1.6 billion of Chevron’s 2020 capital investment and exploration budget towards domestic downstream projects.

Major Write-Downs

Not everything in Chevron’s fracking strategy has panned out favorably. Back in 2010, Chevron announced it was acquiring Atlas Energy for $3.2 billion in cash and would take on its $1.1 billion net debt position at the time. Henry Hub at the time was trading around ~$4 per MMBtu. Here’s a key excerpt from the press release highlighting the assets Chevron was acquiring:

When the transaction closes, Chevron will gain Atlas Energy’s estimated nine trillion cubic feet of natural gas resource, which includes approximately 850 billion cubic feet of proved natural gas reserves with approximately 80 million cubic feet of daily natural gas production. The assets in the Appalachian basin consist of 486,000 net acres of Marcellus Shale; 623,000 net acres of Utica Shale; and a 49 percent interest in Laurel Mountain Midstream, LLC, a joint venture which owns over 1,000 miles of intrastate and natural gas gathering lines servicing the Marcellus. Assets in Michigan include Antrim producing assets and 100,000 net acres of Collingwood/Utica Shale.

For 2019, Chevron allocated $1.6 billion of its capital investment and exploration budget towards other (non-Permian) unconventional plays. That figure is dropping down to “about” $1.0 billion in 2020.

Please note that due to very low natural gas liquids pricing in the US right now, the Utica position Chevron acquired through the aforementioned deal is not worth much. While the Marcellus shale play centered in Pennsylvania is extremely prolific, only Cabot Oil & Gas Corporation (COG) has figured out how to generate consistent free cash flows from the region (read more about our thoughts on the company in Cabot’s 16-page Stock Report here). Chevron will record a massive write-down in the value of its Appalachian position, its stake in the Kitimat LNG project in Canada, and other endeavors during the fourth quarter due to management admitting the economics aren’t there. Here’s more on the issue (emphasis added):

As a result of Chevron’s disciplined approach to capital allocation and a downward revision in its longer-term commodity price outlook, the company will reduce funding to various gas-related opportunities including Appalachia shale, Kitimat LNG, and other international projects. Chevron is evaluating its strategic alternatives for these assets, including divestment. In addition, the revised oil price outlook resulted in an impairment at Big Foot. Combined, these actions are estimated to result in non-cash, after tax impairment charges of $10 billion to $11 billion in its fourth quarter 2019 results, more than half related to the Appalachia shale.

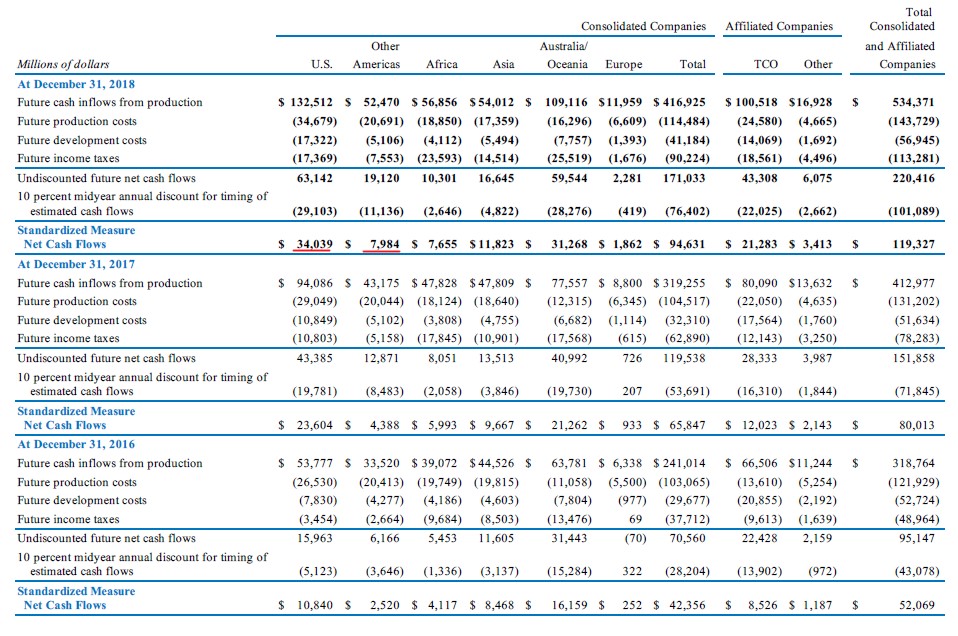

Effectively, it appears Chevron is writing down its entire unconventional upstream Appalachian investment or the vast majority of it. Down below, note the ‘Standardized Measure Net Cash Flows’ figure related to Chevron’s proved oil and gas reserves in the ‘US’ and ‘Other Americas’ regions. In short, this measure is Chevron’s forecast for future asset-level free cash flows discounted at a rate of 10% based on strip pricing near the time the forecast is made. Please note that this latest impairment charge represents a large slice of Chevron’s expected future discounted asset-level free cash flows from the region (based on the forecasts made within its 2018 Annual Report).

Image Shown: Chevron is writing down its North American natural gas investments as global natural gas prices remain subdued. Image Source: Chevron – 2018 Annual Report with additions from the author

Exiting an LNG Export Venture

Chevron’s Kitimat LNG project is a 50/50 joint-venture with Australian-based Woodside Petroleum Limited (WOPEF) that seeks to develop an LNG export terminal in British Columbia, Canada. However, Chevron now plans to sell the stake over concerns regarding low LNG prices stretching on into the future, diminishing the arbitrage economics created by producing natural gas in British Colombia and shipping it over to Asian markets. The development has received various regulatory approvals but has not been sanctioned yet by the joint-venture.

Please note that on a US dollar basis, AECO natural gas pricing (which covers natural gas prices in Alberta and is a useful benchmark in this instance) has historically been trading well below Henry Hub pricing, making LNG exports essential in supporting the upstream economics of this proposed development given just how low regional prices are (in addition to there simply not being enough incremental demand to justify bringing online the kinds of natural gas volumes the Kitimat LNG joint-venture has proposed). Additionally, cheap AECO-priced natural gas supplies enhances the potential arbitrage economics, but we caution LNG development expenses on a per unit basis are generally forecasted to be significantly more expensive in Western Canada than along the US Gulf Coast.

Canadian regulators approved Royal Dutch Shell plc’s (RDS.A) (RDS.B) Canada LNG project last year (which is being developed by a consortium) that’s being constructed in the same region as the proposed Kitimat LNG facility, indicating that regulatory obstacles likely weren’t the top subject on Chevron’s mind when it made this decision. The Kitimat LNG project would require the Pacific Trails Pipeline project to proceed, which would route natural gas supplies from the Liard and Horn River Basins in British Columbia to the export facility (material upstream investments would have to be made to bring those volumes online). The ~470 kilometer long (~290 miles) pipeline project comes with risks but those risks would likely have been manageable. Shell is working with TC Energy (TRP), which will build the ~670 kilometer long (~415 miles) Coastal GasLink pipeline to route natural gas supplies to the LNG Canada facility and LNG exports are expected to start-up by 2024.

It will be extremely hard to find a potential buyer, given the size of the Kitimat LNG stake and considering projects such as these cost *tens* of billions of US dollars. Only a well-funded consortium or another energy major could seriously consider moving forward with the venture. Building upstream, midstream, and natural gas export infrastructure is not cheap.

We view this move as Chevron signaling to Woodside that the company has no intention of ever moving forward with the project versus an attempt to raise cash in the near-term (any divestment agreement will likely take time to secure), meaning Woodside would either need to go it alone (extremely unlikely) or find a new partner if the company wanted to proceed. In other words, this announcement was about removing any ambiguity about Chevron’s future capital investment strategies regarding the Kitimat LNG project considering the venture has been effectively in limbo for some time.

Kazakhstan

In Kazakhstan, a large country in Central Asia that borders Russia and China, Chevron owns (as of the end of 2018) 50% of the Tengizchevroil (‘TCO’) venture which in turn owns the massive onshore Tengiz oilfield. Chevron’s partners include state-run KazMunayGas, Exxon Mobil Corporation (XOM), and Russia’s Lukoil (LUKOY). In addition to the Tengiz oilfield, TCO owns the smaller Korolev oilfield. Also, Chevron owns a 18% non-operated stake in the onshore Karachaganak oilfield and a 15% stake in the Caspian Pipeline Consortium which exports crude oil out of Kazakhstan.

Going forward, the integrated Future Growth Project-Wellhead Pressure Management Project (‘FGP-WPMP’) seeks to boost the Tengiz oilfield’s crude production capacity by 260,000 barrels per day. First-oil from the development is expected by 2022. Chevron’s net production from TCO in 2018 averaged 269,000 barrels of crude oil per day, 19,500 barrels of natural gas liquids per day, and 387 million cubic feet of natural gas per day. Using the 6:1 conversion ratio (as these are international natural gas volumes), Chevron’s net TCO output clocked in at ~353,000 BOE/d net last year. Sulfur that is processed out of the “sour gas” (natural gas with a relatively high sulfur content) is sold by TCO. Back in 2008, TCO expanded the production capacity of the Tengiz oilfield in part by completing the Sour Gas Injection Project.

Chevron’s Kazakhstan operations are an understated part of its upstream growth strategy and represent a key source of future cash flows given the lucrative nature of conventional production streams out of massive onshore oilfields. There are some tail end geopolitical-related risks here, but please note only under scenarios we deem as extraordinarily unlikely (such as a hard war between the US and Russia or the US and China, where Kazakhstan would likely need to take a side, but again that’s very unlikely).

Concluding Thoughts

Chevron’s upstream growth strategy is built around quality assets but shares of CVX already trade at an arguably rich valuation given the numerous headwinds facing the energy industry. We recently updated our models on Chevron, and members interested in checking out more on the name can access its 16-page Stock Report here. Out of the “Big Oil” group, we like BP plc (BP) the most which we cover in greater detail