Image Source: Chevron Corporation – IR Presentation

By Callum Turcan

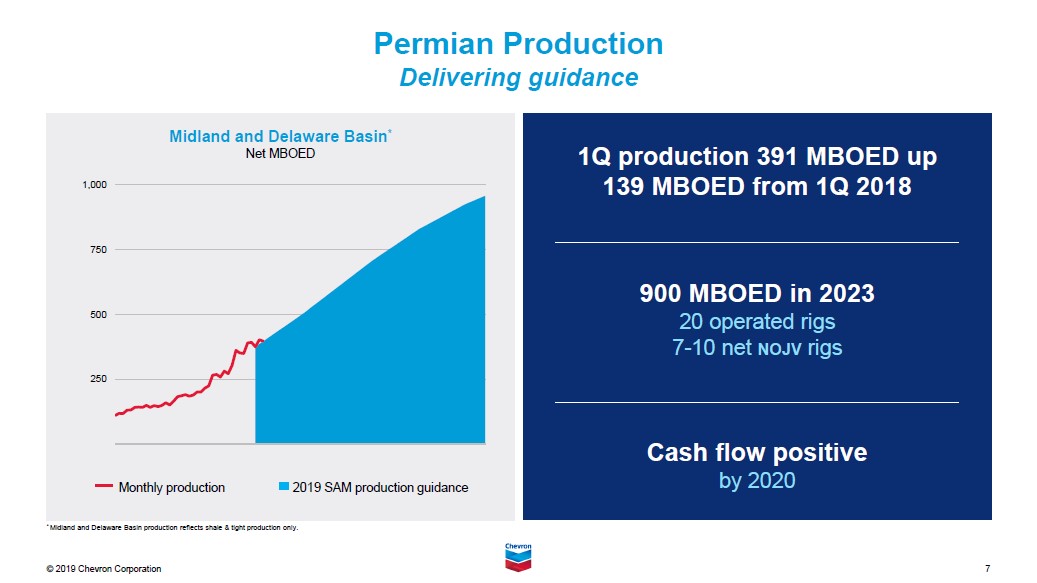

Last year, the storied energy giant Chevron Corporation (CVX) produced 2.9 million barrels of oil equivalent per day on average and the company ended 2018 with 12.1 billion BOE in proved reserves on a net basis. Chevron’s upstream production base climbed by 13% from 2016 to 2018 while its proved reserves increased 8% during this period, led by growth at its Permian Basin operations. Management intends on growing Chevron’s downstream presence to support rising Permian crude oil volumes. We would like to draw attention to Chevron’s Permian operations as we see that having an outsized influence on its growth trajectory. Shares of CVX yield 3.8% as of this writing and are trading modestly over the midpoint of our fair value range.

Texas-sized Ambitions

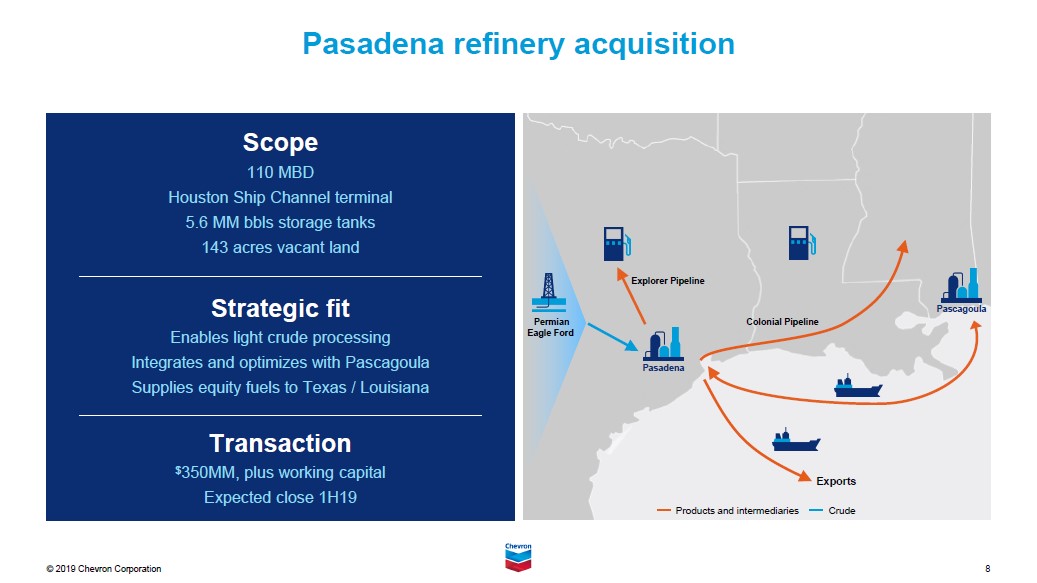

On May 1, Chevron completed its purchase of Petróleo Brasileiro S.A.’s (PBR) small Pasedena refinery in Texas for $0.35 billion (excluding working capital). As an aside, Brazil’s state-run energy company is usually referred to as Petrobras. Chevron acquired the Pasadena refinery and its capacity to refine 110,000 barrels of light oil per day primarily to support its upstream production growth trajectory in the Permian Basin. Unconventional development opportunities in Southeast New Mexico and West Texas, where the Permian is located, are easily repeatable across several plays including the Wolfcamp, Avalon/Leonard, Bone Spring, Spraberry, and others.

Readers should keep in mind these plays are made up of shale (i.e. Wolfcamp), sandstone (i.e. Bone Spring), and other geological formations. As of its June 2019 update, Chevron had an economic interest in 2.2 million net acres in the Permian Basin, 1.7 million of which were prospective for those unconventional plays in the Midland and Delaware sub-basins. A combination of operated and non-operated development activity within the Permian is expected to add 0.5 million BOE/d to Chevron’s upstream production base by 2023 from first quarter 2019 levels on a net basis. That’s an enormous amount of raw energy resource production, a product of Chevron’s upstream Permian volumes marching towards 1 million BOE/d net by the mid-2020s as you can see below.

Image Shown: A vast well location inventory stretched across millions of acres in the Permian supports Chevron’s upstream growth trajectory, which we see as powerful and large enough to have a very material impact on its company-wide results. Image Source: Chevron – IR Presentation

In America, Chevron now owns four refineries (including the Pasadena purchase) and two of those are situated in California. Those two Californian refineries receive crude produced in the state, volumes from Alaska, some domestic sources by rail, and international volumes delivered via marine vessel. Readers should keep in mind Chevron’s downstream presence in California isn’t set up to handle a meaningful amount or any volume from its Permian operations, those upstream volumes generally find their way down to the US Gulf Coast.

West Texas Light is a crude grade with a relatively high API rating (between 40 – 50) and a relatively low amount of sulfur by weight (less than 0.5%). Chevron needs refining capacity that can handle light sweet oil barrels as its unconventional Permian oil output falls within that category, but its California refineries are set up to process large amounts of heavier crudes (the type that is locally produced, which has much lower API ratings and greater concentrations of sulfur). For many reasons, Chevron cannot utilize its downstream presence in California to support its upstream Permian growth story. The Jones Act is another consideration, as that largely prevents Chevron from being able to economically ship oil by marine vessel from Texas to California (in summary, the Jones Act drives up domestic transportation costs by marine vessel if that vessel is moving from US port to US port).

Chevron’s other American refinery is situated in Pascagoula, Mississippi. That facility has the capacity to refine 332,000 barrels of crude per day, making it substantial downstream asset if the crack spreads (refining margins) are cooperative. However, this refinery is out of reach of most of the oil pipelines directly servicing the Permian Basin and numerous other “hot” upstream plays (such as the Eagle Ford in Texas or the STACK/SCOOP in Oklahoma), meaning it doesn’t have ample access to cost-advantaged crude supplies. The facility is dependent on more expensive sources of supply, relatively speaking, than refineries located in Texas. International oil volumes, domestic volumes by barge or rail, and other crude sources are likely used at the Pascagoula refinery (for competitive purposes, only so much information can be given regarding downstream operations). Most importantly, Pascagoula is out of reach of the Permian.

Not having a refinery that could easily tap into Chevron’s growing Permian volumes represented the main impetus behind management deciding to acquire the Pasadena refinery. Note that the city of Pasadena is located right next to Houston along the US Gulf Coast, and that downstream operations in Texas tend to realize some of the strongest crack spreads in America. Particularly those with easy access to foreign markets.

America’s pricing benchmark for crude oil supplies, West Texas Intermediate, trades at a material discount to Brent, which is the benchmark for international oil supplies. That differential stands at $7/barrel for August 2019 deliveries as of this writing. While oil barrels along the US Gulf Coast fetch better prices (based on Houston WTI or Louisiana Light Sweet pricing), selling crude domestically usually isn’t in an upstream company’s best interests. By refining those volumes, Chevron is bypassing the WTI-Brent differential and capturing some nice downstream margin as well. Readers should be aware that the discount Permian oil volumes in West Texas receive relative to WTI, known as the Midland-to-WTI differential, has largely disappeared after ample new pipeline takeaway capacity came online over the past year. If that differential were to reappear, Chevron is now in a much better position to circumvent that potential downside risk.

Potential Downstream Expansion

Going forward, management noted that the Pasadena refinery is supported by its access to the Houston Ship Channel, 5.6 million barrels of storage tank capacity, interconnections to existing crude oil & refined product pipeline systems, and 143 acres of “vacant land” at or near the facility. Having access to the Houston Ship Channel enables Chevron to reach overseas markets where prices for refined products tend to be much stronger. Not only does this bypass the differential problem on the upstream front, but this new asset should provide a nice uplift to Chevron’s downstream operations as the Pasadena refinery’s crack spreads should be quite strong assuming it matches the performance of other refineries in the region.

Due to the sizable upstream oil volumes Chevron is pumping out of the Permian and the enormous amount of energy infrastructure either under construction or already operational in the great state of Texas, the Pasadena refinery has access to all the cost-advantaged crude and sources of demand that it could ever need. As this refinery supports a key part of Chevron’s upstream growth story and offers it a great way to expand its downstream operations (which generate more consistent financial performance relative to the volatile performance of upstream operations), we would be very supportive of Chevron leveraging this new asset to generate additional growth opportunities. That could include Chevron investing in a new CDU, crude distillation unit, at the facility among other things to expand the crude throughput capacity of the Pasadena refinery. We caution that 110,000 barrels per day makes the facility relatively small.

Image Shown: An overview of Chevron’s new Pasadena refinery near Houston, Texas. Image Source: Chevron – IR Presentation

Exxon Mobil Corporation (XOM) is adding a third CDU to its Beaumont refinery, which is also in Texas, in a development that will add ~300,000 barrels per day in crude throughput capacity to the facility. Like Chevron, Exxon Mobil is pursuing this downstream expansion to both support its growing upstream operations in the Permian (where Exxon Mobil is a very big player) and capitalize on the strong economics Texas refineries can generate.

Permian crude oil production has skyrocketed since 2010, and we expect that to continue going forward based on current development plans, albeit at a slower pace. Combined with growing global demand for petroleum products, there appears to be more than enough room for several downstream expansions in the US Gulf Coast region (without ruining the current crack spread paradigm).

Financial Relevance

Chevron’s net operating cash flow jumped from $12.7 billion in 2016 to $30.6 billion in 2018, largely due to a significant recovery at its upstream operations. In 2016, Chevron’s domestic upstream unit posted a loss of $2.1 billion, which rebounded to a profit of $3.3 billion in 2018. Keep in mind we are referring to segment earnings here, which don’t include material corporate-level costs. As a whole, Chevron’s upstream income jumped from a $2.5 billion loss in 2016 to a $13.3 billion profit last year, with its international operations representing the bulk of that income.

Pivoting back to Chevron’s domestic upstream operations. Rising crude oil prices were instrumental in this segment’s recovery of course, but that shouldn’t cloud over how important rising Permian production volumes were as well. Those volumes tend to be quite economical, especially as large portions of Chevron’s Permian acreage are either not burdened by royalties or those royalties are relatively modest. Some Permian upstream operators are forced to pay royalty owners 10 – 25% of the wellhead revenue (across the vast majority of their core acreage holdings), which can be very onerous in any oil price environment. Due to a combination of efficiency gains, cost reductions, economies of scale, and an enormous well inventory in the Permian Basin supporting strong production growth, we expect Chevron to continue growing its domestic upstream income generation capabilities over time at constant realized raw energy resource prices (keeping in mind that fluctuations in raw energy resource prices will always have an outsized influence over its financial performance).

From 2016 to 2018, Chevron’s downstream income expanded by 11% to $3.8 billion, entirely due to its domestic downstream income soaring by 61% to $2.1 billion. Capitalizing on that success is a strategy we are very supportive of, and we expect Chevron to continue growing its domestic downstream income in the future as crack spreads allow. That growth will depend in part on Chevron expanding its crude throughput capacity, which we expect is quite likely within the medium-term (with an eye on potential developments at the Pasadena refinery).

Concluding Thoughts

Large oil & gas companies like Chevron are often sought after for their nice yields and promising growth prospects; however, the space has been undergoing a medium/long-term bust since late-2014. Chevron earned a return on invested capital, excluding goodwill, that was lower than its estimated weighted-average cost of capital in 2018 (its ROIC ex-goodwill were negative in 2016 and 2017). We don’t expect that to change until fiscal 2020 at the earliest, under our baseline assumptions, but we do expect Chevron’s financial performance (and returns) to improve materially through the early-2020s. That isn’t enough to get use excited about Chevron’s shares and its nice yield, but we are monitoring the space at-large.

Oil & Gas – Major: BP, COP, CVX, RDS, TOT, XOM

Related: XLE, USO, OIL

Images in this article are the property of Chevron.

—–

Valuentum members have access to our 16-page stock reports, Valuentum Buying Index ratings, Dividend Cushion ratios, fair value estimates and ranges, dividend reports and more. Not a member? Subscribe today. The first 14 days are free.

Callum Turcan does not own shares in any of the securities mentioned above. Callum Turcan owns shares of BP plc (BP). Some of the companies written about in this article may be included in Valuentum’s simulated newsletter portfolios. Contact Valuentum for more information about its editorial policies.