Image Source: Berkshire Hathaway

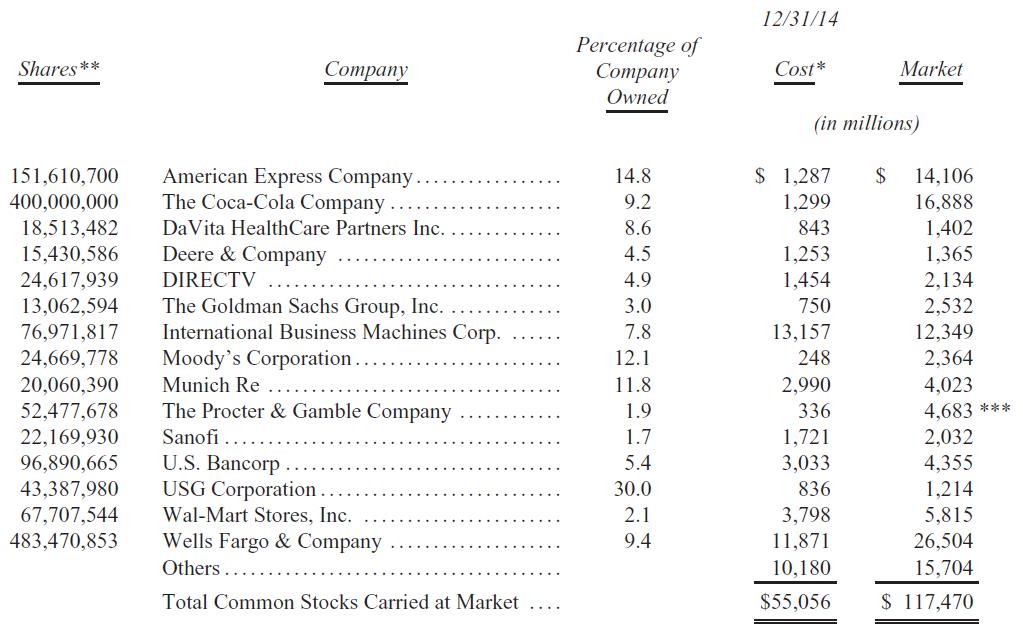

We won’t comment on the top 15 equity positions in Berkshire Hathaway’s portfolio in this article, but we will make the observation that IBM is the sole position that is trading below cost. Most of Berkshire’s positions were established many moons ago, so a higher market value is not saying much. Mr. Buffett tends to hold onto his positions for long periods of time (forever in some cases), which makes the market versus cost comparison in the above table great marketing material for Berkshire stock, but not much more than that. We’re not afraid to lock in gains and remove companies from the newsletter portfolios, even if it means the portfolio doesn’t show as nicely. We have some big gains that are no longer there. Even Mr. Buffett admits that some stocks can get too pricey to hold.

Tickers: AXP, KO, DVA, DE, DTV, GS, IBM, MCO, PG, SNY, USB, USG, WMT, WFC

“The unconventional, but inescapable, conclusion to be drawn from the past fifty years is that it has been far safer to invest in a diversified collection of American businesses than to invest in securities – Treasuries, for example – whose values have been tied to American currency. That was also true in the preceding half-century, a period including the Great Depression and two world wars. Investors should heed this history. To one degree or another it is almost certain to be repeated during the next century.

Stock prices will always be far more volatile than cash-equivalent holdings. Over the long term, however, currency-denominated instruments are riskier investments – far riskier investments – than widely-diversified stock portfolios that are bought over time and that are owned in a manner invoking only token fees and commissions. That lesson has not customarily been taught in business schools, where volatility is almost universally used as a proxy for risk. Though this pedagogic assumption makes for easy teaching, it is dead wrong: Volatility is far from synonymous with risk. Popular formulas that equate the two terms lead students, investors and CEOs astray.”

Warren Buffett’s reference to history is always welcome, and we can learn a lot from the past. It’s important, however, to acknowledge that history is just that, history. It’s over. We’ll always shy away from saying that just because something has been the case in the past, it “almost certain(ly)” will be repeated in the future. History may repeat or rhyme sometimes, but not always. The housing bust of the last decade taught us that this sort of thinking could lead to a disaster of unforeseen proportions.

It’s great to see the reference to volatility and risk. Within our discounted cash-flow valuation model, we do not use a stock-price-derived beta, which can be highly volatile and vary wildly depending on the measurement period. Instead, we use a fundamentally-derived beta that considers the underlying risks of a company’s business model. Not only that, but we also don’t change our long-term forecast of the risk free rate, the 10-year Treasury, in the model too frequently either. Can you imagine how volatile our fair value estimates would be if we tied the discount rate to both the market beta and the spot rate of the 10-year Treasury? We would see 5% or 10% changes in a firm’s intrinsic value or more on a daily basis.

As Mr. Buffett states, stock-price volatility is not a proxy for the risks of a business. Fundamental operating dynamics are the sources of business risk. For example, how volatile is the company’s revenue growth rate through the course of the economic cycle? What’s the operating leverage inherent to the firm’s business model? Share price volatility, on the other hand, offers investors opportunity. Therefore, it should not be considered a factor within the risk assessment. Why should a company’s discount rate go up when the share price falls? The volatility of the stock price should not be a key factor in the investment decision-making process.

The business schools have it wrong.

“If the investor, instead, fears price volatility, erroneously viewing it as a measure of risk, he may, ironically, end up doing some very risky things. Recall, if you will, the pundits who six years ago bemoaned falling stock prices and advised investing in “safe” Treasury bills or bank certificates of deposit. People who heeded this sermon are now earning a pittance on sums they had previously expected would finance a pleasant retirement. (The S&P 500 was then below 700; now it is about 2,100.) If not for their fear of meaningless price volatility, these investors could have assured themselves of a good income for life by simply buying a very low-cost index fund whose dividends would trend upward over the years and whose principal would grow as well (with many ups and downs, to be sure).”

Well said.

“Investors, of course, can, by their own behavior, make stock ownership highly risky. And many do. Active trading, attempts to “time” market movements, inadequate diversification, the payment of high and unnecessary fees to managers and advisors, and the use of borrowed money can destroy the decent returns that a life-long owner of equities would otherwise enjoy. Indeed, borrowed money has no place in the investor’s tool kit: Anything can happen anytime in markets. And no advisor, economist, or TV commentator – and definitely not Charlie nor I – can tell you when chaos will occur. Market forecasters will fill your ear but will never fill your wallet.

The commission of the investment sins listed above is not limited to “the little guy.” Huge institutional investors, viewed as a group, have long underperformed the unsophisticated index-fund investor who simply sits tight for decades. A major reason has been fees: Many institutions pay substantial sums to consultants who, in turn, recommend high-fee managers. And that is a fool’s game. There are a few investment managers, of course, who are very good – though in the short run, it’s difficult to determine whether a great record is due to luck or talent. Most advisors, however, are far better at generating high fees than they are at generating high returns. In truth, their core competence is salesmanship.”

Great comment, though I think Mr. Buffett is a master salesman himself. Within the annual newsletter, there is no shortage of shameless plugs to buy products from the companies in Berkshire’s portfolio of businesses. If Buffett can do it and still be loved by many far and wide, then I’m going to give it a try. If you love what we’re doing here at Valuentum, please recommend our services to friends and colleagues. Even one subscription makes a difference for us.

Berkshire Hathaway’s annual meeting will be held Saturday, May 2, at the CenturyLink Center in Omaha, Nebraska. From our headquarters in Woodstock, Illinois, to Woodstock for Capitalists, I hope you enjoyed my notes thus far. I’ll add more about this year’s annual newsletter in the future.

Sincerely,

Brian Nelson, CFA

President, Equity Research & ETF Analysis