Alibaba (BABA) is trying our patience.

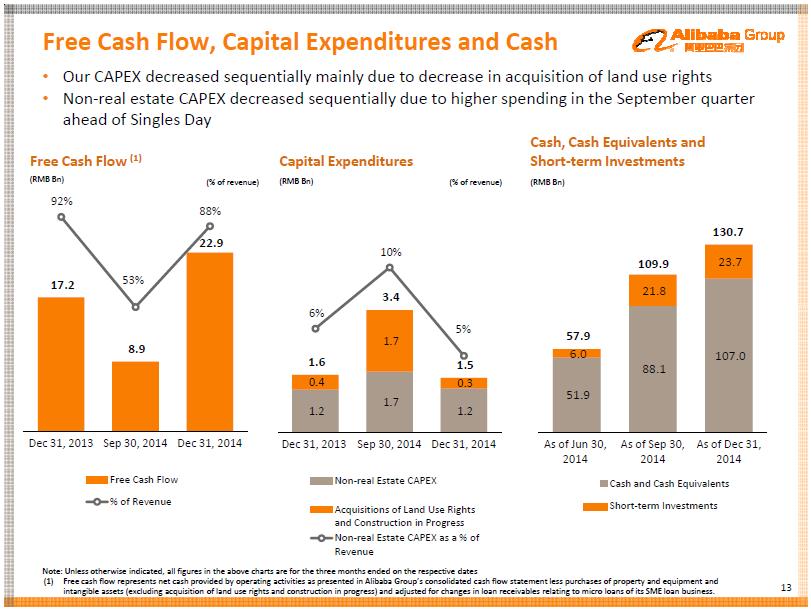

The company’s performance through the first nine months of its fiscal 2015 has been solid. Revenue advanced 45% year-over-year, non-GAAP EBITDA margins were nearly 60% and adjusted free cash flow came in at ~$5 billion. Yes, that’s right – free cash flow of $5 billion, and we don’t give the company credit for changes in its loan receivables in that mark. Disappointing? Hardly. Alibaba’s EBITDA increase in its most recently-reported quarter of 34%, to $2.43 billion, was better than expectations calling for ~24% growth. In our opinion, earnings matter – and Alibaba’s were good!

The company’s shares, however, have fallen into the mid-$80s from ~$120 per share, and I fear that if they break into the lower $80s, there is further sledding to come on the basis of its technicals. A break below its IPO-opening price may create too much overhead supply for any real rally to gain steam. And with the myriad risks outlined in its prospectus, Alibaba has always been a stock that is easy to dislike.

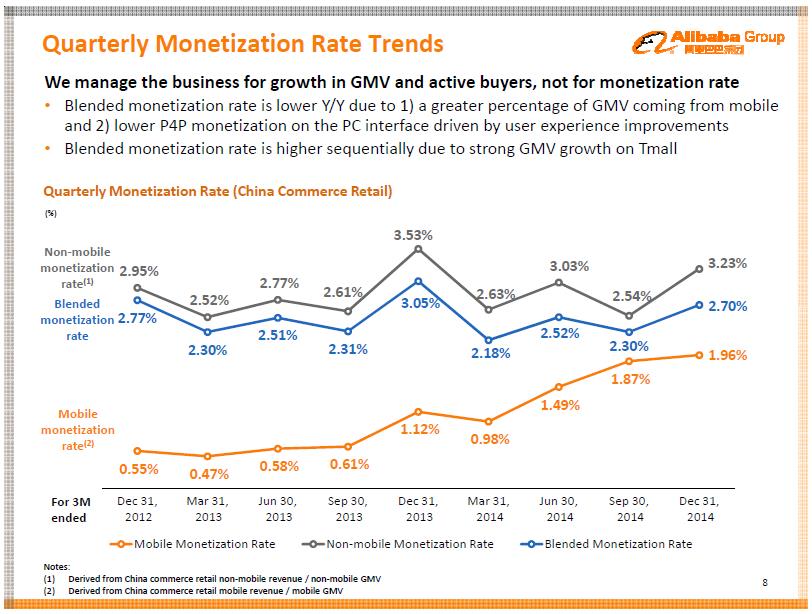

Still, from our perspective, the strong earnings report should have propelled the company’s share price in the other (upward) direction. The market instead is focusing on a few basis-point dip in its monetization rate (the percentage of gross merchandise volumes converted into revenue). The monetization rate is an important metric, but is it more important than revenue growth and earnings expansion?

We think not.

Alibaba may be new to the public markets, but it isn’t a new start-up that is losing money hand-over-fist and failing to convert revenue to free cash flow. Or said differently, Alibaba isn’t Twitter (TWTR), which incidentally saw its shares leap despite recording a $578 million net loss for the year. (You can read about Twitter’s valuation enigma here.) Such price reactions reveal just how silly the expectations game has become, especially when it comes to underlying internal metrics and particularly within tech. Investors seem to be more focused on incremental information than on the most important information. I’ll take better-than-expected earnings and cash flow any day of the week over a metric that Alibaba itself has told analysts it is not focusing on.

Go ahead. Take a look at the slide below: “We manage the business for growth in GMV and active buyers, not for the monetization rate.”

Image Source: Alibaba

It may take some time for the Street to get familiar with what Alibaba can do with its monetization rate. Even a few basis-points change in the normalized, mid-cycle monetization rate, for example, could have a material impact on revenue growth and intrinsic value of Alibaba given the firm’s massive gross merchandise value, which incidentally grew nearly 50% in the most recent quarter.

Still, one quarter shouldn’t have had much of an impact on the analyst community’s long-term forecasts of the company. Even as we admit, however, that technicians will look to break down the stock on any market weakness in coming weeks or months, we’re going to be patient with shares. The company’s free cash flow is solid and growing rapidly. As we often say, it’s not whether GAAP or non-GAAP is more meaningful — it’s all about free cash flow.

Image Source: Alibaba

Infinitely-more speculative entities such as Pandora (P) and GoPro (GPRO) felt the market’s wrath after their respective quarterly reports. Though we don’t think we’ll ever grow interested in either firm in the newsletter portfolios, we want you to be aware of recent developments. Pandora’s shares dropped more than 17%, while GoPro dropped more than 13%, and such moves reveal the fragility of the market’s conviction in each company’s investment prospects.

Pandora’s outlook for its fiscal first quarter came in light. The Internet radio services provider expects revenue in the range of $220-$225 million versus the consensus estimate of more than $240 million for the period, but what really shook the markets was its earnings outlook. Pandora is looking to lose as much as $35 million on the adjusted EBITDA line relative to less-severe loss expectations of ~$10 million. Pandora’s situation is a case where the firm’s operating metrics weren’t bad, but the top and bottom line outlook trumped all. Unlike Alibaba, the market reacted appropriately to Pandora’s performance.

Oh how investors like to talk about GoPro, the adventure camera maker. Will investors ever learn that what determines a good investment is not about finding the “next great technology,” but whether fundamentals–from competitive advantages to future growth prospects–are already embedded in the price at which a company is trading?

The stocks of the great innovators of yesteryear from Microsoft (MSFT) to Walmart (WMT) to McDonald’s (MCD) did not perform well because they revolutionized the computer operating system, big-box retailing, and quick-service restaurant market, respectively. Instead, their stocks had great returns because, in their advent, the market had mispriced their future potential, as measured by their future free cash flows. Their prices “back in the day” did not properly reflect their future fundamentals. If their prices had embedded such fantastic growth, their returns would have been in-line with those of the market.

In investing, it is not about the company or how “cool” or “revolutionary” a technology may be, but whether that company’s future expected fundamental cash flow stream is mispriced. Said differently, is the firm’s share price different than its calculated intrinsic value per share? That’s the question.

Let’s try this. If, for example, someone today wanted to sell us Apple (AAPL) at a million dollars per share, it wouldn’t be a good investment. We can buy shares of Apple for just a shy under $120 today. But if that same someone wanted to sell us Apple shares for $0.50 per share (50 cents per share) today, all else equal, we probable couldn’t buy enough of them. The fundamentals and future prospects of Apple have not changed under either scenario – but only the price at which we can buy Apple has changed. Price matters.

The specifics of any firm’s technology or any other qualitative aspect of the firm will already be embedded in the estimate of a company’s fair value, which considers future expected revenue, earnings and cash flow growth — adjusted for its risk profile. And this estimate of intrinsic value will almost always be different than the firm’s share price.

Ask yourself not about the attributes of the company, but whether such attributes are already embedded in the share price. To us, the answer to intrinsic value is found at the end of the discounted cash-flow valuation process. The foundation of the investment process will always rest in finding valuation mis-pricings.

That said, GoPro issued light earnings-per-share guidance and announced the departure of a key executive in operations on February 5. Though we view both items as transitory, the question again is not whether its camera technology and consumer brand momentum have staying power, but whether such dynamics—when converted into a future free cash flow stream—are already reflected in the stock price.

GoPro is trading at 28 times expected 2016 earnings even after the steep share-price decline. I’ll let you be the judge of the probability that there may be a better entry point in shares yet. But I think there will be.