There is plenty to like about the business models of utilities. Regulated utilities, for one, are monopolies in their operating regions, providing an essential service to businesses and customers. This, coupled with the fact that the returns of regulated utilities are set by a regulatory body within a defined ratemaking process, causes the sector to be full of operators that boast steadily-growing earnings that appear to be materially dependable. As we note in this article, however, a surprisingly large number of utilities in our coverage universe have cut their dividends in the past. Are the dividends of utilities as safe as many make them out to be? Let’s dig in.

By Valuentum Analysts

We frequently receive questions as to why we don’t include a number of individual utilities that have large dividend yields in the Dividend Growth Newsletter portfolio, released and updated on the first of each month via email. While this is a legitimate inquiry, a better question, however, may be: Why is the baseline assumption that we should include individual utilities in the Dividend Growth Newsletter portfolio? Let’s take a closer look at the underlying drivers of the performance of the utility sector in an attempt to properly address such questions. Though conclusions are presented broadly in industry context, it should be noted that each individual utility has its own firm-specific strengths and weaknesses.

We Like Most Utilities

First of all, there is plenty to like about the business models of utilities. Regulated utilities are often monopolies in their operating regions, to which they provide an essential service. This, coupled with the fact that the returns of regulated utilities are set by a regulatory body within a defined ratemaking process, causes the sector to be full of operators that boast steadily-growing earnings that appear to be materially dependable. Often times we warn against capital intensive business models, a key characteristic of utilities, but the regulated aspect of the utility business model reduces a fair amount of the risk associated with such large capital outflows. In fact, it is the fixed rate of return on such hefty investment that is the driver behind regulated utility earnings expansion.

From an analytical standpoint, however, the outlook for the regulatory framework of each individual utility, or its source of revenue and returns, can be very difficult to accurately project with any degree of certainty over the long haul. For example, will regulators complicate the return process, if not during the next few years, what about after that? How timely will regulators allow for payment, or will they not pay in full, if the governing body’s credit deteriorates significantly? There are a lot of questions with answers that may be beyond the forecasting ability of even the most astute and tenured financial analysts. In many cases, the investment analysis of a utility is based more on one’s ability to predict political and regulatory frameworks than anything else.

We’re not alone in this view. Where the financials play a much more important role in the assessment of the credit quality of general operating firms, Moody’s credit rating framework for regulated utilities, for example, is based mostly on an outlook of a given utility’s regulatory environment. Moody’s primary considerations of a utility’s credit quality are based on analysis such as the consistency, supportiveness, and predictability of a firm’s regulatory environment, as well as the historical track record of a utility’s relationship with its regulatory body with respect to the outcomes and timeliness of rate case reviews.

The issue with the above considerations is that such assessments are often backward-looking, and in many cases, a regulatory environment can change suddenly with little or no forewarning, particularly in a politically-charged scenario. Favorable and timely rate case reviews are essential to a healthy operating environment for a utility, as a regulatory body’s decision on the rates a utility is able to charge its rate base is essentially a ruling on the return a regulated utility will receive on its investment. If this process for a given utility has a history of being politically charged, inconsistent, or unfavorable to the utility in any way, it poses a major threat to the utility’s operations moving forward and can result in a lower credit rating for the company.

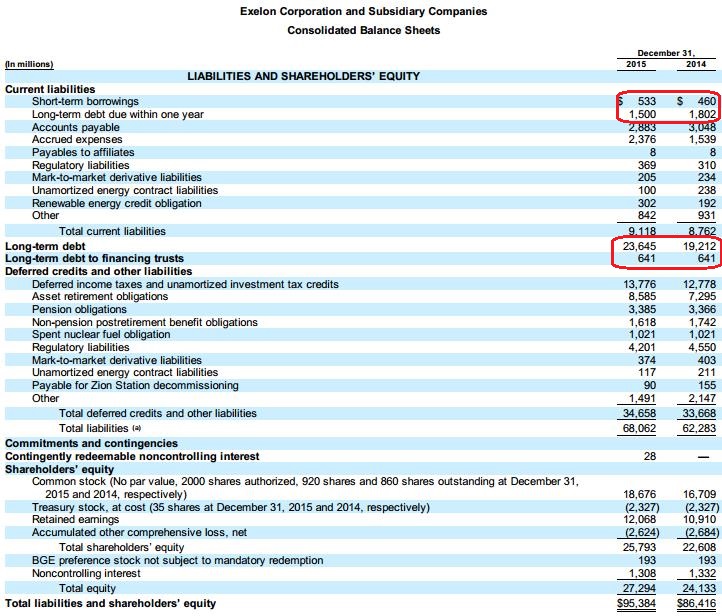

In fact, in Moody’s methodology, only 40% of the credit rating consideration for regulated utilities is based on the actual, tangible financials of the utility itself, and ironically, it is within this particular financial assessment that we tend to disagree with the rating agency’s more sanguine view. From our objective perspective, however, it is also true that most utilities are debt heavy, capital-intensive entities that pay out most of their earnings as dividends, retaining very little cash cushion in the event of an exogenous shock to their business. This is a read straight from the financial statements (see Appendix of this article). In this light, and particularly in the context of a dividend payer, we can’t help but be cautious, as the dependence on estimating the intricacies of changing regulatory environments fails to give us the comfort we would need to accept the added financial risk to the dividend payer.

Though Moody’s notes that the utility sector has experienced few defaults and has a historically high recovery rate in the event of an adverse credit outcome, we think it is important to distinguish between the perspectives of debt and equity investors. The necessary nature of regulated utilities coupled with the political influence over such entities often means that defaults and recoveries across the sector may not be too frequent or severe, respectively, but the ability to continue to pay a dividend is a different question altogether. Where the regulatory “monopolistic” environment surrounding utilities, often credited as the source of most of their “moaty” characteristics, may help stave off a credit event, it may not do much in terms of sustaining the dividend, and we’ll walk through a number of examples as to why.

Some High-Profile Utilities Dividend Cuts

In recent years, there have been two high-profile dividend cuts among major utilities in our coverage universe, the risks of both were highlighted by the Dividend Cushion ratio in advance of their respective cut (a ratio below 1 on the Dividend Cushion signals increased capital dependency, free cash flow shortfalls, an overleveraged balance sheet, or a function of all three). Incredibly, for such a group that comes with a near-pristine “dividend safety” perception from many in the dividend growth crowd, five of the fifteen large utilities in our coverage universe have either cut or suspended their dividends since 2000, and six more of the small/mid-cap variety in our coverage universe have cut or suspended quarterly payouts since 2000 as well. The table at the top of this article showcases the dividend cuts of utility holding companies just in our coverage universe since 2000 (note this includes only utilities from our coverage as there have been many more instances in the past 20 years).

The majority of the dividend cuts highlighted in the table came in the early 2000s, from 2000-2003, due to aggressive growth (capital investment) decisions made throughout the sector in the 1990s. Many utilities attempted to attract investors through unregulated growth projects after being considered too dull compared to faster-growing tech and other stocks at the time. However, as the federal government flirted with the idea of deregulation, the massive move of utilities to build merchant plants to sell power on the open market caused a power surplus and suppressed prices, which were set in the market and not by state regulators. Utilities were forced to take on debt to finance their projects, ultimately causing a cash shortage for a large portion of the sector. Even the largest and most dependable dividend payers were not immune to the cash shortage the industry partially brought upon itself through misguided wholesale power ventures.

American Electric Power (AEP), the largest electric utility in the US at the time, cut its dividend in 2003 after foraying too far from its regulated base in an attempt to capture growth, and TECO Energy (TE) was forced to snap its 43-year streak of consecutive dividend increases in 2003 after unforeseen problems in its large-scale bet on wholesale power sent it scrambling to shore up its financial position. Eight utilities in our coverage universe were forced to cut their dividends between 2000-2003, and in a twelve month period from spring 2002 through spring 2003, thirteen firms with major electric utility operations reduced or suspended their dividends. Many were forced to reduce their quarterly payouts as part of refinancing agreements with creditors as short-term debt raised to finance growth projects matured.

The political forces that were associated with the waffling of both federal and state governments in the late 1990s and into the 2000s were a part of the reason behind the dividend cuts of utilities. The California Power Crisis–which caused multiple utilities to cut their dividends, including Edison International (EIX) and PG&E (PCG) suspending their dividends–is a prime example of the political uncertainty that could crop up around a given utility. The state and federal governments were unable to properly work together, and the utilities involved, their customers, and their investors all found themselves in the dark. We cannot forget to mention the collapse of energy trader Enron around the same time period, which brought additional scrutiny to the energy and power markets, and further clouded the political environment. It is nearly impossible to predict how a politically charged situation will play out, a major reason we point to incalculable firm-specific risk being high in the utility sector.

In more recent memory, Exelon (EXC) cut its dividend in early 2013 due to the expectation for sustained weak market fundamentals across the unregulated power sector. At the time, Exelon owned three utilities and a large power provider, but the majority of the firm’s business came from selling electricity generated in its power plants on the wholesale market. In fact, it was the largest owner and operator of nuclear-power plants in the US at the time, but low natural gas prices and relatively weak electricity demand suppressed unregulated wholesale-power prices and ultimately forced Exelon to reevaluate its capital allocation strategy. Exelon’s credit rating was soundly in investment-grade territory at the time of the dividend cut, mostly due to Moody’s opinion of its regulated utilities operations, which were unable to save the payout.

In 2014, First Energy (FE) became one of the latest large public utilities to join the infamous list of dividend cutting utilities, and the story of its cut is similar to that of its predecessors. The firm had become too dependent on its unregulated power generation business to fund its dividend, and when adverse economic conditions and more costly regulatory and environmental mandates hit, it was sent searching for answers. The company subsequently aligned its dividend strategy with its regulated business, making its payout fully funded by regulated operations. Significant storm activity in the years leading up to the cut also posed an additional headwind to appropriate cash allocation practices for the company, as more than $1 billion in unexpected storm-related expenditures had accumulated. Weather poses yet another unpredictable, exogenous risk to the health of a utility’s operations.

The Dividend Cushion Ratio When It Comes to Utilities

Since its inception a number of years ago, the Dividend Cushion ratio has accurately predicted the heightened financial risk that ultimately led to the dividend cuts at Exelon and First Energy (two highly-rated credits), but such leveraged balance sheets and significant capital requirements–major red flags for any large dividend payer–are not uncommon for most operators in the utility space. The difference came in the two firms’ inability to remain dedicated to their regulated businesses in addition to the increasing amount of regulatory and environmental mandates and general uncertainty surrounding their respective regulatory environments.

Most public utility holding companies in our coverage universe have raw, unadjusted Dividend Cushions below 1 due in part to their large net debt loads, capital-intensity, and dividend obligations. The low raw, unadjusted Dividend Cushion ratios for most utilities don’t mean that we expect them to cut their payouts soon. It just means that they have little excess capital to absorb an exogenous shock to their businesses that may jeopardize the dividend relative to an operating company that generates significant free cash flow and has a huge net cash position on the balance sheet, the combination of which easily covers future expected dividend obligations. Utilities don’t have a lot of “cushion.”

The Dividend Cushion methodology may, in theory, pull forward debt maturities into the 5-year forecast measurement period, generating a more punitive assessment of a utility’s dividend health, but the measure is a more tangible, objective and financial-focused measure of dividend health within and across the utilities sector than issuer credit ratings alone. We think this is a good thing. In this light, the Dividend Cushion, while highlighting risks appropriately, may have a greater number of “false positives” in the utilities sector regarding the extent of dividend risks than in other sectors due in part to the greater dependence on qualitative, non-financial analysis in assessing the fundamentals of utilities operations, and by extension, a utility’s ability to keep paying a growing dividend. However, as even the past 20 years have revealed, utilities’ dividends aren’t always safe.

From our perspective, we’ve reluctantly accepted the reality that publicly-traded utilities are almost entirely dependent on the regulatory environment to offset the well-documented balance sheet and free-cash-flow risk associated with their operations. For those that are uncomfortable knowing that pure and dependable financial analysis may be but a secondary consideration in determining the dividend health of an individual utility, sector utilities ETFs, such as the diversified Utilities Select SPDR ETF (XLU), become a much more attractive alternative. This is the camp that we generally find ourselves in. We’d much rather consider a dividend payer with a considerable net cash balance that is generating significantly more free cash flow than dividends paid (as those in the Dividend Growth Newsletter portfolio). Such characteristics are not common within the utilities sector.

Concluding Thoughts

Though we’ve made the case why investors should be aware of the abnormal firm-specific risks to the dividend of any individual utility position, exposure to the broader sector may still make a lot of sense for a number of reasons. Not only are there diversification benefits to holding a broad basket of utilities stocks, but held in aggregate, they also provide income (and sometimes dividend growth) benefits to a portfolio. However, given the Fed’s aggressive rate-hiking cycle in 2022, the positive yield spread between utility dividend yields and the risk free rate of near-term U.S. Treasury bills is no longer attractive. This has made them comparatively less attractive as income vehicles.

Utilities equities are generally considered “safer” investments relative to most other business models due in part to their fixed rate of returns through regulatory support and “monopolistic” characteristics that are common to their operations. Where consumer or industrial operating equities are beholden to sometimes punitive rivalries and cyclical economic trends, utilities are in part shielded from such dynamics. All of this sounds great, but that doesn’t mean their dividends are iron-clad. Investors may continue to flock to what classically have been considered among the safest dividend payers on the market, but this is a distinction we’ll leave you to decide it is fair or not.

Appendix

I. Understanding the Net Debt Positions of Utilities

II. Understanding the Free Cash Flow Shortfall (cash flow from operations less all capital expenditures) of Utilities

—–

NOW READ (July 9, 2023): MUST READ: 17 Capital Appreciation Ideas In A Row!

NOW READ — Questions for Valuentum’s Brian Nelson

NOW READ — ALERT: Big Yield Additions to Dividend Growth Newsletter Portfolio and High Yield Dividend Newsletter Portfolio

NOW READ — ALERT: Going to “Fully Invested” in the Best Ideas Newsletter Portfolio

NOW READ — Expect Huge Equity Returns This Decade, Much More Volatility However

NOW READ — There Are No Free ‘Income’ Lunches

Categories Member Articles