By Brian Nelson, CFA

“Netflix is valued as if it will have the economics of three US operations, without having to pay at all for the next two…”

We have no problems with investors playing with “fire” if they know that they are and don’t mind losing their shirts, but we posit that, given the popularity of the acronym, FANG, which stands for Facebook (FB), Amazon (AMZN), Netflix (NFLX), and Google, now Alphabet (GOOG, GOOGL), many unsuspecting investors have been lured into Netflix believing these four companies share similar qualities. They absolutely 100% do not. On one hand, Facebook, Amazon, and Alphabet have incredibly strong balance sheets and generate copious amounts of free cash flow, as measured by cash flow from operations less all capital spending. On the other hand, Netflix doesn’t.

Let’s explain. Facebook ended 2015 with cash and marketable securities of $18.4 billion and no debt, Alphabet ended the year with $73.1 billion in cash and marketable securities and a modest debt load of $5.2 billion, good for a net cash position of $67.7 billion, while Amazon ended 2015 with $19.8 billion in cash and marketable securities against a long-term debt load of $8.2 billion, good for a net cash position of $11.6 billion. Facebook generated over $6 billion in free cash flow during the year, with the fourth-quarter coming in at over $2.1 billion. Alphabet generated free cash flow of $16.1 billion, with more than $4.3 billion of that coming in the fourth quarter. Amazon pulled in $7.3 billion in free cash flow for the year.

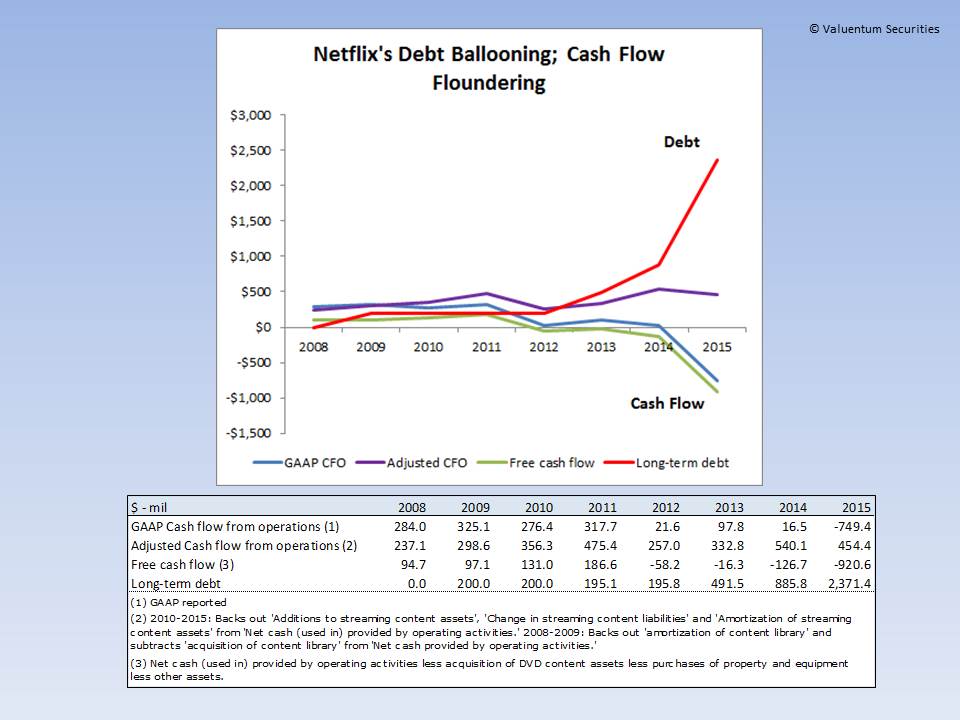

Netflix, however, is nothing like these companies at all. The company, for one, swung to a net debt position at the end of 2015, as it burned through a total of $921 million (negative) in free cash flow during the year, losing $276 million in the fourth quarter alone. Where the balance sheets of Facebook, Amazon, and Alphabet are enormously cash-rich, and free cash flow generation is phenomenal, accelerating in Facebook’s case and “turning-the-corner” in a big way at Amazon, Netflix’s balance sheet will only get worse following expected debt raises in late 2016 and early 2017 that will only be accompanied by continued free cash flow burn. We’ve applauded CEO Reed Hastings in the past for being straightforward, “Don’t Take Our Word For It; Ask CEO Reed Hastings; Netflix’s Shares Are Overpriced,” but the recent euphoria in ‘FANG’ stocks could really do damage to those that believe that Netflix is anything like the other three.

So what do we think?

First, forget GAAP versus non-GAAP. Forget the bear cases that you’ve heard many a time before. Let’s instead talk cash and common sense. A tried-and-true way to sum up equity value in a back-of-the-envelope fashion for illustrative purposes is on the basis of a standard perpetuity function in the context of enterprise free cash flow, and then adding net cash or subtracting net debt from that “perp” value. In this case, let’s assume that the balance sheet is a net-neutral proposition for Netflix, even though we know the company will be adding to its financial burden in coming months. Let’s also further suspend reality and assume that all expenses (including content or otherwise) at Netflix are FREE (costless), meaning that revenue equals enterprise free cash flow (“fantasy”). Let’s assume that single-B-rated (“junk”) Netflix’s cost of capital approximates ~12%, a modest premium to the ~9-10% all-in bond yields in the high-yield market, January 21 (Moody’s); a cost of equity, by definition, is greater than the all-in cost of debt, and Netflix remains predominantly equity-funded (market cap/total cap), tilting the weighted average cost of capital higher. Though the first assumptions are imaginary, the discount rate is quite reasonable, in this case.

Let’s move forward. In “perping” Netflix’s revenue as enterprise free cash flow ($6.779 billion/0.12), we’d arrive at a “pretend” equity value, one in which revenue equals enterprise free cash flow and assumes a net-neutral balance sheet, of $56 billion. That’s if all expenses were free, and if revenue were enterprise free cash flow, and the company didn’t need debt again…ever. Throw a 50% operating margin on that stream and that gets you to a $28 billion equity value. Throw Netflix’s 4.5% operating margin on that stream, and you guessed it. Okay — you may say we haven’t considered “growth,” but yet, implicitly we have.

Let’s look at it another way. To back into Netflix’s now present $40 billion market capitalization, assuming a 12% discount rate, the question to ask is the following: what normalized enterprise free cash flow would the firm have to achieve to justify the current price level? Since we can effectively (and generously) assume a net-neutral balance sheet, let’s multiply $40 billion and 0.12 (the discount rate) to find the answer: $4.8 billion. Said differently, in order to justify Netflix’s current price level, assuming no further free-cash-flow burn or incremental financial leverage, Netflix would have to throw off as much as $4.8 billion in enterprise free cash flow per annum going forward to justify its existing stock price.

Even if you make the leap that the company “wants” to lose money, burn through free cash flow, leverage up the balance sheet, can anyone really make the case that normalized enterprise free cash flow at Netflix is 70% of its existing revenue stream when content costs are through the roof and “contribution” margins, even in the US, are nowhere near that level? Firmwide operating margins are in the mid-single-digits, traditional free cash flow was nearly negative $1 billion in 2015, and if you annualize the contribution profit from its US business based on its first-quarter 2016 expectations, the $1.7 billion mark comes up short in a big way. Netflix is valued as if it will have the economics of three US operations, without having to pay at all for the next two, and assuming the US business holds the line…into perpetuity.

What to expect going forward? It would appear more of the same, as most of the company’s investor base is focused irrationally on growth “metrics” rather than stress-testing free-cash-flow-based intrinsic value calculations for reasonableness. Said differently, many investors believe Netflix will continue to do well because it has done so in the past. You got it: it has all the makings of a bubble. The esteemed Professor of Finance at the Stern School Business at NYU Aswath Damodaran, “The Disruptive Duo: Amazon and Netflix,” sets an intrinsic value of Netflix at the low end of the Valuentum fair value range, in the low-$60s, and we maintain our view that things could get a lot worse, “Alert: 5 Reasons Why We Think Netflix’s Shares Will Collapse.”

Netflix is growing rapidly, if only to muddy the waters for analysts, but you’re not going to convince us that the company is worth 120+ peak (2009) GAAP cash flow from operations and nearly 90 times adjusted cash flow from operations, a measure that excludes the “mess” in Netflix’s cash flow from operations section of its cash flow statement: ‘Additions to streaming content assets’, ‘Change in streaming content liabilities’ and ‘Amortization of streaming content assets.’ We think it’s time again for CEO Reed Hastings to remind Netflix investors that the stock is overpriced, and extremely at that?

The numbers don’t work.