Why You MUST Stay Active in Investing

I don’t care what kind of indexing propaganda you show me. I’m never playing Russian roulette with my money. I want to know the cash-based intrinsic values of the companies in my portfolio, and that's something worth paying for, regardless of the performance of active versus passive. I care more about what could have happened as a measure of risk than any measure of actual standard deviation. That’s why active management is so valuable. It should help you sleep at night.

By Brian Nelson, CFA

Staying active has tremendous long term health benefits including reducing the risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes. We all know this. Sure, we can stay passive on the couch with a bag of chips and the game on, but we know that a sedentary lifestyle will come back to bite us…eventually.

I feel the same way about the conversation about active versus passive when it comes to the health of your retirement savings. There may not seem like there’s anything wrong with sitting on the recliner for days at a time or not counting calories (like one evaluates future free cash flows), but eventually it will catch up to you.

This article isn’t a lesson on healthy living, per se, though if this inspires you to get moving and eat wiser all the better. Instead, this is a lesson on why you must stay active in the stock market and monitor your portfolios frequently, resisting the urge to sit on the couch and hold those unhealthy index funds. Just like a sedentary lifestyle with your personal health, you’re taking a big risk with your personal wealth in index funds whether you see it or not.

In finance, we see a lot of randomness that we try to explain with “science” or “human behavior,” but the observation may be nothing more than coincidence. Did you know that if the majority share of fund managers during the period 1963-1998 had outperformed the S&P 500 Index in just five more years, the number of years that the majority share of mutual funds would have outperformed the S&P 500 index would have been greater than half during this 36-year period?

Here, a largely random dynamic, but finance has written a far-reaching narrative around the active versus passive debate. It goes something like this: “Money managers are not skilled. You can’t beat the market. Fees are too high to outperform. Costs matter above all else. You get what you don’t pay for.” The narrative has grown so prevalent that researchers such as S&P and Morningstar do not even compare money managers to a universal benchmark like the S&P 500. Instead, they are largely comparing fund managers against benchmarks that are close to the fund managers’ own portfolios and are somehow surprised to learn that fund managers cannot outperform a benchmark that approximates their own portfolio after fees.

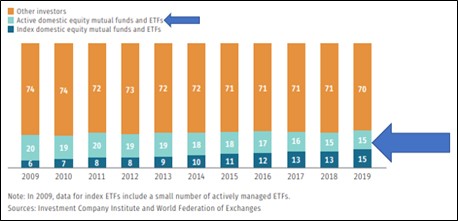

This isn’t research – this is manipulation. Of course, I mean this in the nicest way possible. The reality is that nobody truly knows how the field of active management is performing. Not only are studies not showing how funds are performing relative to the S&P 500 Index, but we don’t even have all the data on active management, itself. For example, studies that measure the performance of active fund and ETF managers are looking at just 15% of the stock market.

Image: Active domestic equity mutual funds and ETFs represent just 15% of the stock market, hardly enough data to make any conclusions about the merits of individual stock selection. Source: ICI.

The indexing narrative has been built around a random outcome woven over years. When it comes to fund analysis, I care more about the distribution of the performance of active mutual funds and ETFs versus the S&P 500 Index. It is a much better gauge of the merits of active management, in my view. For example, I care more about identifying in advance that large cap growth will outperform the S&P 500 Index than I do in the performance of large cap growth funds versus their large cap growth benchmark. I want to know where investors can outperform, not whether the majority of funds in that area of outperformance are beating their benchmark after fees. What good is an outperforming fund relative to its benchmark that isn’t beating the S&P 500 Index?

In finance, we can’t be hasty to jump to conclusions to wrap a narrative around the randomness we witness. What if those five years during 1963-1998 had gone the other way, and the majority share of active funds outperformed the S&P 500 Index in more years over that period? What if the incentive of index licensing fees and quant investing didn’t take off this century, where the concept of investing seemed to change to “factors” as active funds were measured against a very close benchmark instead of the S&P 500 Index?

In his book, Fooled By Randomness: The Hidden Role of Chance in Life and in the Markets, Nassim Nicholas Taleb addresses the important concept of alternative histories. What the notion comes down to is that we shouldn’t judge the quality of a strategy or an investment decision based on how actual history played out, but rather by the costs of the alternative, or if history had played out in different way. To better explain what I am getting at, here is an excerpt from his book:

Clearly, the quality of a decision cannot be solely judged based on its outcome, but such a point seems to be voiced only by people who fail (those who succeed attribute their success to the quality of their decision).

[…]

One can illustrate the strange concept of alternative histories as follows. Imagine an eccentric (and bored) tycoon offering you $10 million to play Russian roulette, i.e., to put a revolver containing one bullet in the six available chambers to your head and pull the trigger. Each realization would count as one history, for a total of six possible histories of equal probabilities. Five out of these six histories would lead to enrichment; one would lead to a statistic, that is, an obituary with an embarrassing (but certainly original) cause of death. The problem is that only one of the histories is observed in reality; and the winner of $10 million would elicit the admiration and praise of some fatuous journalist (the very same ones who unconditionally admire the Forbes 500 billionaires). Like almost every executive I have encountered during an eighteen-year career on Wall Street (the role of such executives in my view being no more than a judge of results delivered in a random manner), the public observes the external signs of wealth without even having a glimpse at the source (we call such source the generator.) Consider the possibility that the Russian roulette winner would be used as a role model by his family, friends, and neighbors.

While the remaining five histories are not observable, the wise and thoughtful person could easily make a guess as to their attributes. It requires some thoughtfulness and personal courage. In addition, in time, if the roulette-betting fool keeps playing the game, the bad histories will tend to catch up with him. Thus, if a twenty-five-year-old played Russian roulette, say, once a year, there would be a very slim possibility of his surviving until his fiftieth birthday— but, if there are enough players, say thousands of twenty-five-year-old players, we can expect to see a handful of (extremely rich) survivors (and a very large cemetery).

[…]

The reader can see my unusual notion of alternative accounting: $10 million earned through Russian roulette does not have the same value as $10 million earned through the diligent and artful practice of dentistry. They are the same, can buy the same goods, except that one’s dependence on randomness is greater than the other.

The role of alternative histories comes into play when discussing the COVID-19 pandemic. Indexers, for example, point to odds that the probability of a loss for the S&P 500 from January 1930-January 2021 over any rolling 5-10 year-period is 10%-19%, or about 1 in 6, which just happens to be the chances of getting the bullet in the chamber.

Indexers are in many ways playing a game of Russian roulette. They are playing the odds just like that twenty-five-year-old with the gun to their head. The fool that keeps playing the game is eventually going to regret it, and an alternate history related to COVID-19 is a great place to grasp what I’m talking about. Let’s excerpt from the second edition of Value Trap to understand:

“…if it were not for the bold Fed and Treasury actions taken during both the Great Financial Crisis and COVID-19 crisis, practitioners of indexing, modern portfolio theory and the efficient markets hypothesis would probably start to fall out of favor. Many capital-market-dependent assets held in index funds would have gone to $0 due to credit unavailability, correlations would have been even more nonsensical (approaching 1 across asset classes), and active investors would have outperformed tremendously as passive investors were caught like a deer in headlights. Never again would fiduciaries be able to use the efficient markets hypothesis as an excuse to not evaluate business fundamentals and calculate intrinsic values--considerations that efficient markets theorists seem to take pride in not doing.”

In an alternate history, a vast number of companies in index funds were wiped out during the COVID-19 pandemic. Congress/Fed/Treasury refused to bail out anybody. The medical community did not deliver on a COVID-19 vaccine in time to stave off massive human devastation. Asset correlations became nonsensical, relegating most quant analysis to the trash bin.

Obviously, this alternate history did not happen. But just because index funds were not devastated this time around does not make the strategy of indexing wise. This alternative history exists, even if it is not observable, as does the bullet in the chamber.

In 2020, indexers pulled the trigger of the revolver when COVID-19 hit, and this time the chamber was empty. But as indexers keep playing Russian roulette, will the chamber be empty next time? That’s why I’d go so far as to say that paying a 2% annual fee for a great manager that focuses on in-depth intrinsic value analysis is worth it.

That said, when I refer to active management, I don’t necessarily mean active funds or ETFs. I’m referring to active stock selection--or choosing an active fundamental-focused manager that is heavily experienced in competitive-advantage and discounted-cash flow analysis--a manager that knows what his companies are worth. Certainly not quant funds: During the period 2010-2019, for example, Nomura estimates that more than 50% of U.S. quant mutual funds underperformed the market in 8 of those 10 years.

I don’t care what kind of indexing propaganda you show me. I’m never playing Russian roulette with my money. I want to know the cash-based intrinsic values of the companies in my portfolio, and that's something worth paying for, regardless of the performance of active versus passive. I care more about what could have happened as a measure of risk than any measure of actual standard deviation. That’s why active management is so valuable.

It should help you sleep at night.

-----

Valuentum members have access to our 16-page stock reports, Valuentum Buying Index ratings, Dividend Cushion ratios, fair value estimates and ranges, dividend reports and more. Not a member? Subscribe today. The first 14 days are free.

Brian Nelson owns shares in SPY, SCHG, QQQ, and IWM. Brian Nelson's household owns shares in HON. Some of the other securities written about in this article may be included in Valuentum's simulated newsletter portfolios. Contact Valuentum for more information about its editorial policies.

1 Comments Posted Leave a comment