The Best Years Are Ahead

publication date: Apr 7, 2021

|

author/source: Brian Nelson, CFA

By Brian Nelson, CFA

By Brian Nelson, CFA---

The wind is at our backs.

---

The Federal Reserve, Treasury, and regulatory bodies of the U.S. may have no choice but to keep U.S. markets moving higher. The likelihood of the S&P 500 reaching 2,000 ever again seems remote, and I would not be surprised to see 5,000 on the S&P 500 before we see 2,500-3,000, if the latter may be in the cards. The S&P 500 is trading at ~4,100 at the time of this writing.

---

The high end of our fair value range on the S&P 500 remains just shy of 4,000, but I foresee a massive shift in long-term capital out of traditional bonds into equities this decade (and markets to remain overpriced for some time). Bond yields are paltry and will likely stay that way for some time, requiring advisors to rethink their asset mixes.

---

Capitalism Is Hanging On By A Thread

---

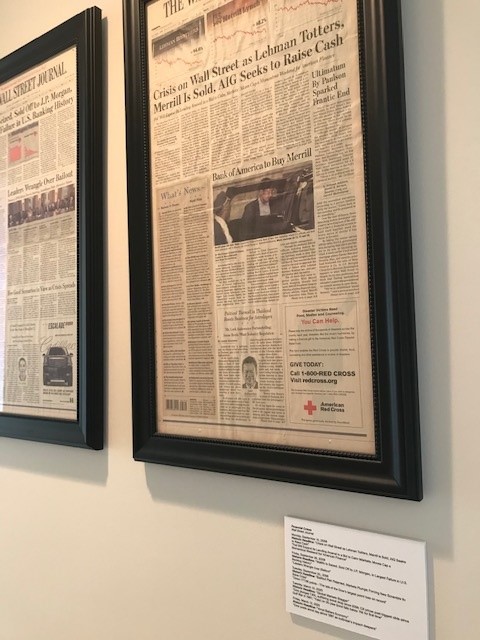

The stock market looks to be the place to be long term, as it has always been. With all the tools at the disposal of government officials, economic collapse (as in the Great Depression) may no longer be even a minor probability in the decades to come--unlike in the past with the capitalistic mindset that governed the Federal Reserve before the “Lehman collapse.” See Image.

---

We saw temporary Great Depression-like numbers during the COVID-19 meltdown last year, as we had predicted concurrent with our expectations of the market’s melt-up, but the economic pain was neither prolonged nor substantial. Today, we are in a state of controlled capitalism, holding on to the last shred of free markets that we can, if we can.

---

Under a pure capitalistic system, our financial structure would have failed almost certainly with the fall of Lehman in 2008, and we would have had a massive eradication of wealth at the top.

---

Years later, with COVID-19, restaurant owners, airlines, and customer-facing enterprises would have gone under, facilitating another massive wealth transfer from owners to workers and new entrepreneurs when the recovery from COVID-19 ensued.

---

Instead, during the Great Financial Crisis, homeowners were thrown out of their houses, while the banks were bailed out. During COVID-19, businesses that recklessly bought back stock prior to the crisis stayed intact, while workers suffered again.

---

Government officials saved the “whole” by making the wealthy even more wealthy. A 20% return on $10,000 is $2,000, but a 20% return on $10,000,000 is $2 million. Wealth inequality has widened.

---

Many students are struggling to pay off their student loans. Watching Operation Varsity Blues: The College Admissions Scandal on Netflix made my stomach churn.

---

It made me think that the donations made to universities to put their names on buildings may not truly be a form of philanthropy. It may be the worst sign of vanity. Damian Lewis’ character Bobby Axelrod in Billions may have shown us the real reasons for this type of “philanthropy.” Ego.

---

As we all know, the ultra-rich have been very, very lucky to have stayed that way the past two decades. In the capitalistic system that built this country, new financial entities would have risen from the ashes of those that should have fallen during the Great Financial Crisis.

---

Most of the restaurant chains and luxury and leisure entities should have failed during COVID-19, paving the way for new leaders and new faces. I feel the coming generation may be completely fed up with this, and this is why we’re seeing Reddit revolutions, capital uprisings, and crypto creation.

---

I’ve never met Jamie Dimon, but in an alternate history, Jamie is not the billionaire that he is today, but rather a banker that lost it all during the Great Financial Crisis, like many did during the Great Crash of 1929. Many of the index fund promoters would have lost so much capital during COVID-19, too, if capitalism was allowed to “work.”

---

We have very few captains of industry anymore – those that truly built companies from the ground up.

---

The Path of Least Resistance Is Higher

---

Where am I going with this?

---

Well, in my opinion, only the rarest of the rarest black swan event may take the markets down in a meaningfully painful way for one to consider underweighting equities this day and age. To a very large degree, we’ve substantially limited the risks of sustained economic collapse, much like we have eradicated polio and how we’re working to do the same with COVID-19.

---

It may seem the markets are rigged to work for the rich (and that might not be wrong), but this is the chess game we’re all playing. The Fed and Treasury are chess pieces that one has to account for in one’s analysis, just like economic growth and earnings expansion. It may not be fair that the hedge fund that bet on a huge decline prior to COVID-19 still lost money when the Fed and Treasury bailed everyone out again.

---

But that’s how it works.

---

I headed up the valuation infrastructure during most of the Great Financial Crisis at Morningstar. I knew what the Fed and Treasury did. I knew they would do it again during the COVID-19 meltdown. We were on the right side of the “trade” in 2020 at Valuentum because we knew the game we were playing. I think it would be terrible to be “right,” and the Fed and Treasury destroy your thesis.

---

But you have to understand that you must account for all the chess pieces, not just the ones you want.

---

Sometimes, I still wonder why the Fed and Treasury let CEO Dick Fuld’s Lehman fail, but I don’t think government officials at the time truly wanted to throw in the towel on capitalism. They wanted to hold on to it dearly even just a dozen years ago, but when the markets tanked that September day in 2008, U.S. finance changed for all time.

---

Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan showed us how we can create a massive housing bubble after the dot-com bubble, and after the burst, how we’d still all be better for it. The precedent had been set. With any economic problem, the Federal Reserve and Treasury will throw everything it can at it, and I mean everything. We’ll be better off…eventually.

---

After about 20 years in this business, I feel confident that, if needed, the Fed and Treasury would even go so far as to purchase stocks outright--even in a more deliberate manner than when the banks were nationalized, in part, during the Great Financial Crisis. No policy measure is off the table. Absolutely nothing.

---

I even believe that the Fed and Treasury would set stock prices, if they had to, just like they set interest rates. If one thinks hard about it, it’s actually not that far of a leap. The greatest risk today, in my opinion, is not being in the markets at all. The second greatest risk is pursuing a too-diversified approach to wealth creation, stretching too far to hold alternative asset classes while overweighting bonds.

---

By my estimates, modern portfolio theory (MPT), as measured by a simple 60/40 stock/bond portfolio that was rebalanced by a financial advisor that charges 1% per annum did materially worse than the average active fund manager that was paid a 2% annual fee during the past 30 years or so. Let that sink in.

---

Had you hired an average active stock manager in 1990 and paid 2% per year for their skills, by my estimates, you would have come out far ahead than had you hired the most brilliant quant portfolio theorist applying a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio.

---

Perspective is everything.

---

For long-term investors, active stock investing was by far the better option. Since the early 1990s, the SPY has crushed the Vanguard Balanced Index Fund Investor Shares (VBINX) that invests roughly 60% in stocks and 40% in bonds.

---

The Concept of “Believability”

---

So, what is preventing progress?

---

I see a couple possible explanations. When you’re an up-and-comer, it is extremely difficult to go against Nobel prize winning work as in modern portfolio theory and the efficient markets hypothesis. I have read so many different books mostly out of fear that my views are wrong, but as I keep reading and reading, I only gain more and more conviction in my beliefs.

---

Harry Markowitz, who set the stage for modern portfolio theory, didn’t have a grasp of investing, according to the writings of Peter L. Bernstein. Eugene Fama’s early work on the efficient markets hypothesis, to my knowledge, only really reveals that one shouldn’t day trade. It’s actually quite unsettling when you think about how influential Markowitz and Fama have been on finance. From Value Trap:

---

"Fama’s efficient markets hypothesis presupposes that the distribution of price returns of fairly-valued, undervalued, and overvalued stocks may be independent, identically distributed in successive forward one-time periods, but this may not take into account the core component of investing. That is, it may take each stock uniquely more than one period--not successive days or weeks or months, but rather sometimes years--to be categorically reclassified as a result of both price and fair-value-estimate movements (i.e. an undervalued stock’s price advances to become fairly valued). That price returns may be independent, identically distributed in successive one-time periods across undefined sets of fairly-valued, undervalued, or overvalued stocks may not, or rather should not, translate into the view markets are efficient, or that stocks are priced correctly."

---

Ray Dalio’s Principles speak to the idea of “believability,” as defined as follows: “The most believable opinions are those of people who 1) have repeatedly and successfully accomplished the thing in question, and 2) have demonstrated that they can logically explain the cause-effect relationships behind their conclusions.”

---

It's hard to go against Nobel prize winning work such as modern portfolio theory, even when the numbers speak to substantial evidence of its failure – and what about the traditional “quant value factor” in Fama’s three-factor model? One can’t reasonably link cause and effect to a simple price-to-book ratio when one knows that big companies such as Boeing (BA), McDonald’s (MCD) and Domino’s (DPZ) have negative book equity, right?

---

But Nobel prizes work magic when it comes to establishing “believability.” Markowitz’s work has “believability,” even as the concept falls short empirically. Fama’s work has “believability,” even as it makes little sense logically. Many may extrapolate the term “believability” to “inertia” as things that make little sense keep being repeated over and over and over again.

---

But I wonder – for these two Nobel prize winners, I might wager that between the both of them combined, they may not have built a half dozen discounted cash flow models in their entire lives. I always found it puzzling that we believe in “quant factors” of stock returns that are derived by the very same individual that believes in random markets. It’s like asking an atheist to write the Bible.

---

I remember Marty Whitman having a big issue with Fama’s Nobel prize. Shiller received his prize the same year as Fama, and Shiller is a big inefficient markets guy. These inconsistencies won’t stop the Nobel prize from being a “believability” factor in the minds of others, however.

---

But you should be suspect.

---

Massively Underperforming Computers in Finance

---

Whitman may have recognized the prospects for the gamification of the markets a long time ago when he called Fama’s work “utter nonsense.” I’m not convinced of quant “believability,” but I will explain why others fall into the trap of quant “believability” through the context of computers.

---

As I continue to study some of the most well-respected minds out there in the financial world, there are some similarities. Morningstar’s Joe Mansueto took advantage of the early age of computers when building his company. Ray Dalio did the same with Bridgewater. Those that adopted computers early on were ahead of the curve. Perhaps the fourth edition of Jim O’ Shaughnessy’s What Works on Wall Street explains as much:

---

"It took the combination of fast computers and huge databases like Compustat to prove that a portfolio’s returns are essentially determined by the factors that define the portfolio. Before computers, it was almost impossible to determine what strategy guided any given portfolio. The number of underlying factors (characteristics that define a portfolio like price-to-earnings [PE] ratio, dividend yield, etc.) an investor could consider seemed endless. The best you could do was look at portfolios in the most general ways.

---

Sometimes even a professional manager didn’t know which particular factors best characterized the stocks in his or her portfolio, relying more often on general descriptions and other qualitative measures. Computers changed this. We now can analyze a portfolio and see which factors, if any, separate the best-performing strategies from the mediocre. With computers, we also can test combinations of factors over long periods, showing us what to expect in the future from any given investment strategy."

---

The promise of computers was great, but in finance, it wasn’t just the computers themselves, in my opinion; it was really the public perception of computers in other fields and their impact in other fields that mattered. In the 1960s, companies would change their names to include the word “electronics” or “tronics” -- Astron, Vulcatron, Circuitronics, Videotronics, and the like to get a nice pop in their stock price. In Random Walk, Malkiel talked about how a phonograph company, American Music Guild, changed its name to Space-Tone to see its shares soar. Malkiel says, “The name was the game.”

---

Computers have been extremely helpful in building the productivity of America, but that positive perception of computers in other fields has created a “halo effect” around the name and its variants in finance such as “quant,” “algorithms,” “artificial intelligence,” and “machine learning”—as well as the vast statistical data applied to the work (“Big Data”). Many successful entrepreneurs in finance, in my view, have found success during the past several decades due merely to the perception of the efficacy of computers in finance--not necessarily the logic backing their views driving such calculations.

---

I won’t go into my discussion of the pitfalls of backward-looking factors in this note (you can read Value Trap for that), but “quant,” “algorithms,” “artificial intelligence,” and “machine learning” are the Astron’s, Vulcatron’s, Circuitronic’s and Videotronics of our day. In my opinion, a computer can only be as talented in understanding the markets as its programmer, and today’s quants are crunching yesterday’s numbers to try to predict the future when it’s future expectations at any time in the past that matter.

---

No amount of quantitative work, algorithmic proficiency, artificial intelligence, or machine learning is going to help if the very structure of the marketplace--that share prices are influenced by the intrinsic values derived by forward-looking discounted cash-flow analysis--is not understood or embraced. Just like the Astron’s, Vulcatron’s, Circuitronic’s, and Videotronic’s of the 1960s (and the dot com “wannabees” of the late 1990s”), the psychology name game has worked to raise lots of capital in finance.

---

People want to sound “smart,” and they know how to play off people’s mental models. It should therefore be no surprise that “Big Data” has become popular in finance, as a response to the preferences of clientele in other fields such as medicine, physics and beyond. However, there’s an important reason why empirical asset pricing models have had to be revised since their inception. In finance, the backward-looking data these empirical models apply is useless when it comes to asset pricing--unlike the usefulness of empirical data in the physical world.

---

To a large degree, those that adopted computers early on were the great “name changers” (not game changers) of their day.

---

In many respects, it didn’t come down to the quality of their product, per se, but rather the perception of the quality of the product. “Believability.” As we’ve seen in the demise of hedge fund Long Term Capital Management, which was stacked with quantitative statistical talent and the best computing power money could buy at the time, perception of “smart” can be a very hazardous proposition for investors. Recent investors of Renaissance Technologies' external funds felt some serious pain in 2020, too.

---

I remain open to all considerations in finance, but I view the use of the terms “quant,” “algorithms,” “artificial intelligence,” and “machine leaning” not as innovations in finance, but rather as red flags. Those that use them are purveyors of great name changing, not innovation. Stock prices and returns are driven by future expectations of free cash flow. "Empirical" and "evidence-based" are two other sales terms that should signal caution.

---

When I hear these “catch phrases,” I think of Malkiel and his story about the door-to-door phonograph company that changed its name to Space-Tone to drive its stock price higher. Similarly, these concepts have raised lots of capital, but it’s just a name game, and no amount of name changing will alter the fact that more than half of quant funds have underperformed the market in 8 of the past 10 years.

---

Just How Fashionable Is “Brain Science”

---

People want to share and repeat “smart” things. Jonah Berger says in Contagious, “People share things that make them look good to others.” In some respects, this has helped ESG (environmental, social, corporate governance) investing. It’s much easier to share info about a company with a high ESG rating than it is to share tobacco giant’s Altria’s (MO) long-term price history. Many of us dislike Facebook (FB) due to privacy issues, but its shares are about as attractive as a stock can get.

---

What I’ve also learned about successful entrepreneurs is their use of “brain science,” or it least their application of talking about “brain science” in conversation. I remember having a number of conversations with now-deceased famous money manager Richard Driehaus about left brain/right brain thinking. Ray Dalio had a similar influence, it seems, on the importance of how the brain impacts human behavior. Richard Thaler’s success, in part, has also been highly influenced on how the brain works through the works of Kahneman.

---

Certainly, how we make decisions impacts our results, and the inner workings of our decision-making engine (“the brain”) matter, but like the quant Nobel prize winners, I wonder if we can count on one hand the number of discounted cash flow models these great thinkers have built.

---

How do they know they are making a behavioral mistake when they have not calculated the value of the asset that they are considering purchasing? Without an in-depth understanding of the discounted cash-flow model in finance, it's like trying to cure cancer without an understanding of the cellular make-up of the human body in medicine.

---

Behavioral finance is on shaky ground in that respect.

---

By no means is this article intended to be a catchall of the traits of successful entrepreneurs and money managers, but with some of the greatest ones, using positive perception (as in the advances in other fields such as computers) and tapping into the social currency of looking smart through “brain science” talk seem to be overlapping traits leading to success.

---

The systematic process of Valuentum investing seems to capture these two areas, in my view. For example, there may be no more advanced quantitative data-driven structure than the discounted cash-flow model that arrives at a fair value estimate of a company, and capturing the market’s perception of value as in technical/momentum indicators in the Valuentum philosophy captures the behavioral “brain science” part.

---

Active Stock Management Is Actually Pretty Good

---

As we’ve seen in the example of the SPY versus the 60/40 stock/bond portfolio during the past 30 years, “believability” acts as a huge impediment to productive change. From my perspective, modern portfolio theory seems to have cost American investors billions over the past three decades, while saving them little in volatility during the worst crises. The SPY dropped just 8 percentage points more than the 60/40 stock/bond portfolio during the worst of the COVID-19 crisis, while pursuing the 60/40 stock bond allocation cost investors over 100 percentage points during the decade before that.

---

One might conclude that this observation supports putting one’s money in a low-cost S&P 500 index fund, but that’s just looking at the past. We don’t know what will happen in the future. Nobody knows. We have a pretty good idea that stocks will outperform bonds, and while indexing the SPY may be better than a 60/40 stock bond split in the long run, there’s a ton of room for a talented active stock manager to take on measured risks to do even better. In fact, a November 2018 article written by Morningstar has shown that active managers have skill:

---

"To put this performance in perspective, if an investor hypothetically invested in every U.S. stock fund on Oct. 1, 1998, and rebalanced each month thereafter (weighting each fund investment by its assets), her gross returns over the subsequent 20 years would have exceeded all but 20% of the U.S. equity funds that began the period."

---

Let’s think about this for a second.

---

The average stock fund outperforms on a gross basis, so that means that in many respects owning a grouping of active funds that paid out an even higher than 2% annual fee still did better than the 60/40 stock/bond portfolio during the past 30 years. The quants always then say – “Well, we need to adjust this for risk.” – as if their measures of risk are absolute. Should we adjust for the irrelevant P/B ratio as a measure of “value,” or market cap as a measure of "size," or why not revenue or "size" of earnings?

---

I think maybe you’re getting my point: Quant finance may be far more subjective than fundamental analysis, which in many cases is highly qualitative, and it seems like such quant risk adjustments are made only to show that markets are efficient after adjusting for backward-looking factors. It’s all circular thinking. Pretty soon, we've forgotten about what we're talking about in the first place, that the SPY crushed the VBINX over a 30-year period!

---

But what is the most appropriate measure of risk? In my opinion, the biggest risk factor is time. For example, stock market risk is reduced when one’s time horizon increases; as one’s time horizon decreases, stock market risk increases. With many people living longer and healthier lives-- some may even live 30 years in retirement or longer--the bigger issue facing advisors today is whether investors, even those in retirement, are taking on enough equity exposure.

---

My general view is that most of quant analysis represents thinking “inside the box.” I can almost feel their reluctance to deviate from Nobel prize winning work, even to accept a truism as simple as stock prices and returns are based on forward-looking expectations. But it’s not just this that eats at me. There seems to be a stampede of professionals hell bent on destroying active stock management--even as active stock management has absolutely trumped the widely acclaimed 60/40 stock/bond portfolio the past three decades.

---

Price-Agnostic Trading: A Friend Until The Markets Implode

---

Price-agnostic trading is trading that shifts the burden of price discovery to others. When there’s more of it, price-discovery weakens. When less of it, price discovery strengthens. The application of broad stock diversification and modern portfolio theory through rebalancing contributes little to price discovery, sometimes distorting it.

---

As more and more price-agnostic trading proliferates, the composition of total risk to the market changes, even if the amount of total risk stays the same. Idiosyncratic risk, or firm-specific risk, is reduced while systematic risk is increased. If everyone indexed and just rebalanced their portfolios periodically, we’d all be taking on only systemic risk. Pretty scary, right?

---

Some like Jack Bogle would call this scenario “chaos.” The long-term consequences of a market where firm-specific risk is continuously transformed into systemic risk--as evidenced through increased asset price correlations-- remains uncertain. However, what is very probable is that index funds in holding every company are misallocating investor capital.

---

Should indexers have been involved in airlines heading into the COVID-19 meltdown, for example? Most active managers knew the big risks they were taking in airline equities, but I don’t think indexers had much of an understanding. When markets collapsed during the COVID-19 meltdown, the Fed and Treasury simply had no choice but to bail out airlines (and indexers, too).

---

After all, how could the Fed and Treasury let capitalism in its purest sense work by wiping out airlines (and restaurants) when most Americans are just plowing their life savings blindly into these stocks via indexing at the advice of Nobel prize winners and the largest asset managers in the country. The whole system would look downright silly, and we’d have 10 LTCMs all at once.

---

Indexers aren’t doing much good for society, but rather, indexing and price-agnostic trading are merely shifting systemic risk and costs to the taxpayer. The taxpayer is essentially footing the bill for the mistakes and misallocation of capital that index funds facilitate, much like the taxpayers had to bail out the banks during the Great Financial Crisis for their loose lending and reckless leveraging of derivatives.

---

The only scenario that I see for the Fed and Treasury to be able to let the market system (capitalism) work once again, if that may even be the goal anymore, is if the SEC seeks to break index funds due to systemic risk and facilitate and incentivize price discovery and its positive externalities by rewarding active management. We tax a lot of goods that can lead to negative consequences such as alcohol and cigarettes.

---

Why not index funds, too?

---

Without this very, very unlikely development, it’s my belief that all government agencies will continue to act essentially as one unit to drive equity prices higher and higher and higher. They may have no choice. How can they let families around the country that have bought into the “magic” of not paying attention to asset prices by buying low-cost index funds and following MPT go bust?

---

In my view, the government will not let indexing and MPT fail because they simply can’t, and it’s important that active managers understand this. Regulators dropped the ball on clamping down on indexing years ago, and now systemic risk has been transferred to the taxpayer.

---

Though the argument may be that we’re all better for the bailouts that prevented the absolute obliteration of capitalism the past two decades (because there was milk in the store after Lehman failed and we didn’t get the breadlines due to COVID-19), it still is somewhat unsettling that we have moved far away from a meritocracy.

---

Moral hazard continues to be rewarded.

---

The Gamification of the Markets Began a Long Time Ago

---

Today’s flood of free capital by the government printing presses through ultra-low interest rates and runaway government spending is also creating new instruments such as non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and what I describe as “fake” coins such as Bitcoin. These things really should not exist, but if you have enough people that believe in them, perception becomes reality.

---

I’m still learning about NFTs and crypto (as they are unnecessary to do well in markets and in life), and even though I own a small digital wallet to learn the system, I cannot take these items seriously at the moment--at least not any more than I can take baseball cards or fine wine, even though I love collecting the latter two as a hobby (not as an investment).

---

It’s clear the gamification of the markets didn’t start with the Reddit/Robinhood crowd and Gamestop (GME) and AMC Entertainment (AMC). It really started when the industry drifted away from intrinsic value analysis with the advent of modern portfolio theory and "factor" investing.

---

A 25-year old Markowitz who “knew nothing about the stock market,” according to Peter L. Bernstein, when he wrote “Portfolio Selection” in 1952 at the University of Chicago has had such wide influence. Markowitz saw no need to stand on the shoulders of the giants before him.

---

Now, however, with the SPY crushing the VBINX for the better part of my lifetime--there still has been no movement in finance on this consideration for now what has become 70 years. Why? “Believability.” “Inertia.” But American investors have lost billions on the concept of MPT.

---

What are they to do?

---

Well, the very idea of just blindly investing in index funds without regard to what could happen in “alternate histories” -- not what has happened as in the measure of risk of standard deviation -- may be irresponsible. That’s why having an active stock manager that really knows what they’re doing is priceless, in my humble opinion.

---

It may be a difficult pill to swallow for some, but when one thinks about the growth of passive management and the likelihood that most of the money flowing into index funds is weighed down by MPT, ebullience should turn into shock. Price-agnostic trading is costing investors hundreds of billions, maybe trillions, and yet here we are with most of finance applauding it.

---

When taking standardized tests, we often are told that we should stick with our first answer, which is often correct. The first answer in finance was Burr’s Theory of Investment Value and Graham’s Security Analysis. These bodies of work have, to a large extent, grown into the thoughts we find in the book Value Trap.

---

With Peter L. Bernstein having passed away years ago, it’s going to be difficult without his work and writings to put my finger on the tipping point as to how finance ended up costing investors so much of their life savings on price-agnostic trading (e.g. indexing and MPT), and I do admit my view is a highly unusual take and perspective...

---

...but, then again, so were my thoughts on MLPs in 2015 (before its collapse) and my thoughts on the “value factor” in 2018 (before its collapse).

---

I don’t think Jack Bogle was the catalyst for the mess. I don’t think Morningstar in their holdings-based analytical fund-rating framework is entirely to blame. I don’t think the efficient market hypothesis is totally to blame. I don’t think MPT is the worst thing in the world.

---

Space-Tone does sound a lot more exciting than American Music Guild so I can understand how some might be lured to quant finance. I also can understand the lure of gambling and picking the ponies, so I get how a bunch of P/E ratios and PEG ratios looks a lot like the program at the track. Gambling is addictive. I get how talking about “brain science” is one heck of an interesting topic.

---

But what I don’t get is how finance can do so much “wrong” for retirees, and yet not see it. I think it has become clear that our two biggest faults as humans are ego and blind spots, in this case the latter, more than the former. Has finance been blinded by science? But could it also be greed? I’m not so sure either. After all, those practicing MPT and indexing lost out on huge gains during the past three decades.

---

Wrapping Things Up

---

The “socialization” of the markets--through expected government intervention when things go bad--coupled with centralized management of systemic risks (driven by price-agnostic trading) makes betting against the market in the long run a very difficult proposition.

---

This is especially true when the government owns the printing press and when stocks are priced nominally, not in real terms. Since price-agnostic trading is allowed, and indexing and MPT are huge considerations, the government just can’t afford to let these strategies fail, regardless of their merits.

---

But I argue that even so, there are still better approaches than these.

---

For one, alternate histories as that which could have happened following the COVID-19 outbreak suggest we can’t just park our money in broad index funds and forget about it, and terrible underperformance with little volatility enhancement during crises indicate a stock/bond mix may not be best bet for most investors.

---

I believe active stock management with the right manager is the best option for most long-term investors. In the long run, my analysis suggests a 2% management fee leaves a substantial positive cushion relative to the 60/40 stock/bond portfolio while providing the potential for further outperformance via measured risk taking.

---

Price-agnostic trading will once again rear its ugly head, but I believe the stock market is the place to be with the right manager that understands the risks.

---

---

Kind regards,

---

---

Brian Nelson, CFA

President, Investment Research

Valuentum Securities, Inc.

brian@valuentum.com

Tickerized for stocks in the SPY.

-----

Valuentum members have access to our 16-page stock reports, Valuentum Buying Index ratings, Dividend Cushion ratios, fair value estimates and ranges, dividend reports and more. Not a member? Subscribe today. The first 14 days are free.

Brian Nelson owns shares in SPY, SCHG, QQQ, DIA, VOT, and IWM. Brian Nelson's household owns shares in HON. Some of the other securities written about in this article may be included in Valuentum's simulated newsletter portfolios. Contact Valuentum for more information about its editorial policies.

1 Comments Posted Leave a comment