What Goes Up… Well, You Know the Rest

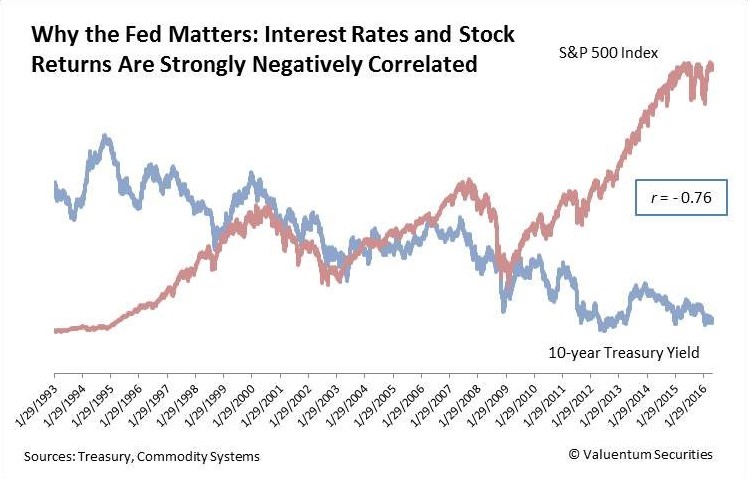

Groundhog Day proved to be painful for the markets. Though a few companies disappointed with respect to their earnings reports, the real reason for the sell-off is two-fold: the market is overpriced by most metrics and Treasury rates, used within valuation frameworks, are rising.

By Brian Nelson, CFA

Many were surprised by the market’s big fall during the trading session February 2, 2018. We’re not. We wrote up a recent piece that said even a 1%-2% decline may be nothing when it comes to truly evaluating historic bear markets, which can zap as much as 40% of wealth in just a couple years, “2018 Starts Out with a Bang!:”

Though we continue to believe that readers should exercise caution due to existing stock market valuations, which are frothy regardless of how you measure them, whether it’s the forward price-to-earnings ratio on the S&P 500, or the cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings ratio, or the market-cap-to-GDP ratio. But that may not matter. What many seem to be caught up on is that we are currently in a bull market, and that means that investors buy, and they hold, and without meaningful volatility in the markets these days, there’s not much to give the long-term investor to think about when it comes to reasons to sell. The self-perpetuating cycle of a steadily-increasing market with ultra-low volatility has taken many an investor by surprise, and even the most experienced of market observers can hardly believe it. We’d be remiss to say that the current magnitude and duration of the ongoing bull market is unusual, however. Perhaps this may be where optimists are gathering excitement.

For starters, if you look at the bull market that ended with the dot-com bust, stocks advanced more than 816%, representing an annualized return of ~19%, from the Crash of 1987. It took nearly 13 years to achieve this remarkable run. If we go back to the bull market than ended with the Crash of 1987, that was a near-13-year run, too, with a return of more than 845%, marking a 19% annualized return, too. There have been two other bull markets in market history with durations of nearly 14 years and over 15 years, with total returns of 800%+ and 900%+, respectively, meaning that today’s bull market could still be in the middle innings if history is any guide and if it is of the longer-duration variety. The average duration of a bull market is ~9 years, however, with average cumulative total return of 480%, meaning that if today’s bull market is only of the average variety, it is starting to get long in the tooth.

How did we get here? For starters, ultra-low interest rates and a flood of liquidity by the Fed, which has caused many an investor to jump into risky assets for yields. Second, the proliferation of indexing and/or buy-and-hold investors that aren’t paying attention to the price-to-fair value equation, but instead to other considerations (“put money to work” and the like), is generating a buy-at-any-price mentality, what many consider to be the primary cause of any stock market bubble. Third, a generally strong US economy that has not been exposed to exogenous shocks or systemic events for some time, though one could possibly point to Brexit, the London Whale incident, the property/stock markets in China, or even the threat of nuclear war with North Korea--but nobody seems to care. Fourth, the March 2009 panic bottom may have been the greatest cause of this bull market, a generational low, perhaps shaking out some of the most reasonable and/or most emotional of investors for good, and they may have never come back.

For some to have witnessed this much wealth evaporate during such a recent event as the Financial Crisis, for example, it’s hard to believe that the stock market could ever be considered a long-term wealth creator--but it has bounced back, and it may very well be because of the idea that the market has bounced back from the depths of ruin in late last decade, and in a big way, that investors may no longer be paying attention to it. They may say: “Buy and hold. Index. Reinvest Those Dividends. Keep Putting Money to Work. Get Started Saving as Early as Possible.” After all, if today’s investor believes the market always goes up, will it continue to be a self-fulfilling prophecy? Or will game theory take over and that one incremental investor that decides to get out eventually lead to the beginning of the end of this bull market? It has to end some time, right? Here’s the real deal: the bull market is going to work until it doesn’t, and valuations aren’t going to matter until they do. Unlike bull markets, which are long, slow marches higher, bear markets are fast and cut deep (and are very painful). According to First Trust, “the average bear market lasted 1.4 years with an average cumulative loss of ~41%.”

I think you need to start thinking, if or when, we do enter the next bear market, whether you might be able to handle a 40%+ loss in your wealth. This is why I want you to keep paying attention to the markets and your money--because if you believe in bull markets and you buy into what is driving the market today, then you have to also believe in bear markets, and we all know what happened during the very worst of the bear markets following the Crash of 1929. That bear market lasted less than 3 years, but it wiped out more than 80% of wealth in the US stock market. It’s a story nobody wants to remember, but it is one we should never forget. Sometimes it’s easy to get caught up in the latest and greatest financial instrument, or the buy-and-hold mentality, but you should also pay attention to price-versus intrinsic value. Nobody has ever been hurt taking profits, to my knowledge, but many an investor has gotten hurt being greedy.

Many may point to somewhat disappointing earnings reports from the likes of Apple (AAPL), Google (GOOG, GOOGL), Exxon Mobil (XOM), and Chevron (CVX), but the reality is that the stock market is just not cheap, and risk-free yields are rising. I talked extensively about how the forward price-to-earnings ratio is far above its historic 5-year and 10-year averages, and how rising yields act as an offsetting dynamic to corporate tax cuts. If the increase in risk-free yields is severe enough, it can completely offset any benefits from tax reform.

I think the stock market, after a prolonged Trump rally, is finally coming around to realizing that corporate tax receipts will be substantially weakened, particularly from the new capital expensing provision, during the next recession, if or when it comes--and the US government may need to take on even more debt to offset the tax shortfalls. The US dollar is also tanking relative to a basket of currencies, as the world grows more concerned about the US’ fiscal situation.

Going forward, I continue to believe the 10-year Treasury yield will be the most important variable to keep your eye on. What that benchmark rate does from here on out may even be more inversely-correlated to stock returns, given how sensitive valuation models might be when working from an ultra-low interest-rate baseline.

Enjoy the weekend!

Related: SPY, DIA, QQQ