Economic Roundtable: Quant Quake, “Quac-cidental Correlation,” and Economic Moats

Image Source: Anders Sandberg. Tickerized for holdings in the DIA.

Last week, the markets may have revealed that internals aren’t all that healthy. Major equity markets experienced a “rotation” that reminded many investors of the “quant quake” from August 2007. As Valuentum’s Brian Nelson wrote in Value Trap, “just a few bad days in the market caused a rapid unwinding of many quant long-short strategies (back then). Goldman’s chief financial officer said at the time that the firm was witnessing ‘25-standard deviation moves, several days in a row.’”

On the surface, markets last week seemed relatively calm, but as the episode in 2007 revealed the activity last week may just be the calm before the storm. Many are pointing to overcrowded trades in betting against certain factors, while others are saying that many were forced to deleverage. We’re not so sure, and we think it may be the opposite: after years of suffering from lagging “value” returns, we think several quant shops stepped in to take on leverage, betting on a return to “value.”

We’re going to talk about last week's quant quake, spurious correlations (the “guac-cidental correlation, in fact), economic moats and much more. Let’s get things started with a prompt from the Financials Times, “Drop in hot stocks stirs memories of ‘quant quake:’

The stock may appear tranquil again after a rollercoaster summer, but many analysts and investors are unnerved by violent moves beneath the surface, reviving memories of the 2007 “quant quake” that shook the computer-driven investment industry.

“This is a rare event, and might morph into something bigger,” said Mr. Luo. “The 2007 quant crisis hinted at much bigger, and more fundamental issues[this sell-off might also hint at much bigger problems.”

Brian Nelson: Great topic. Here’s a thread from the author of the piece, Robin Wigglesworth, which pulls a number of quotes from the article and provides some background on factor investing: https://twitter.com/RobinWigg/status/1172154279102210048. I do think that what we’ve witnessed this week is an important indication of the systemic risks that quants are causing to market structure.

Further, I object greatly to how many are presenting factors today as “driving” returns, per J.P. Morgan’s Marko Kolanovic’s quote below. I think this misunderstanding may be why backward-looking, ambiguous factor investing has become so popular--because people think that many of the most widely followed factors “drive” (cause) returns. They do not.

See Kolanovic’s quote below, as background.

Image Source: Robin Wigglesworth

I think it’s a communication issue. Technically, any factor can “explain” anything (“explain” is just the terminology of statistics). Guacamole prices can be a factor to “explain” Bitcoin returns, for example (see image below). But we all know this relationship is spurious -- of course guacamole pricing doesn’t drive/cause Bitcoin returns, but it can statistically “explain” the returns through best-fit models. The important consideration is whether the factor is causal or drives the returns. Guacamole prices don’t drive Bitcoin returns any more than size or B/M “value” factor drive stock returns.

Image Source: Petrit Selimi. The Bitcoin-avocado price correlation dates back to June 2018 through May/June 2019, but while avocado prices may have “explained” Bitcoin returns over this time period, to a degree, we know this relationship is spurious. The relationship subsequently broke down, as expected.

It is highly probable that the use of the statistical term “explain” may be the primary cause for the huge misunderstanding we see today with many believing many ambiguously derived quant factors actually “drive” returns. Let me repeat: if factors are based on backward-looking, ambiguous and realized data, they simply cannot be causal and are very likely spurious. I really think investors are just confusing correlation with causation or confusing the term “explain” with “drive” or “cause.” To some degree, this misunderstanding could very well be the foundation for quant’s popularity today. The three-factor model has failed (the three-factor model is a regression model developed by University of Chicago’s Eugene Fama to apply statistics to try to “explain” stock returns).

The size factor doesn’t really exist; the B/M value factor has pretty much inverted; the CAPM (Capital Asset Pricing Model) is completely wrong. It’s a structural issue why quant models keep failing: Stock returns are based on future expectations, realized or not. At the very core is that they are using realized data that doesn’t consider future expectations. As a truth seeker and one that cares very deeply about investors getting the best and correct information, I feel an obligation to share these things to our readers. Nobody is talking about this, however.

In fact, today’s research environment is so unusual that instead of saying that the CAPM is completely wrong and giving Warren Buffett credit for saying that volatility is just not a good measure of risk (return), finance calls something that doesn’t line up with incorrect research a “low vol” anomaly (low volatility stocks outperform high volatile stocks, contrary to the CAPM). Similarly, instead of saying that the “growth” versus “value” conversation is nonsense, as Buffett said in 1992 Letter, now that B/M has failed for decades, quants merely say “growth” is outperforming “value.” It’s almost as if quant can’t be wrong. Anything that disagrees with the "original" peer-reviewed academic research is an anomaly or just some transient curiosity--same thing happened decades ago with efficient markets hypothesis (EMH).

Not only have the quants “stolen” the language of investing, but the reality is that as more and more of the quantitative foundation is proven incorrect, it’s becoming more and more difficult to get around the “language” barrier to truly help investors. I am very, very concerned. As Nobel winner Richard Thaler said about EMH and how papers had to be apologetic when they came across evidence that contradicted the EMH, it just seems like when the quants get something wrong, there is just something wrong with the “right” answer because the quants just can’t be wrong.

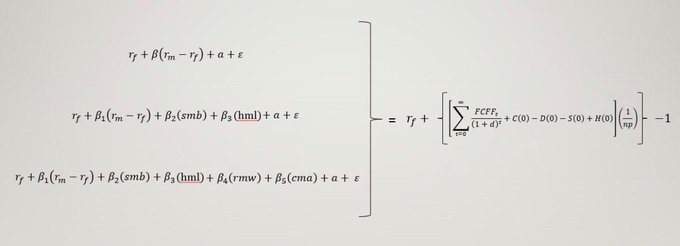

I think the perception of investors believing backward-looking ambiguous factors “drive” returns has caused the environment and the “zoo of factors” that has Research Affiliates’ Rob Arnott saying he wants quant to get its act together. Many are pointing to many of these factors as risk premiums, that investors are being “compensated” for them, but the expected return function of any equity considers forward-looking data (the FCFF is forward looking, image below). Factor models that try to explain returns are merely best-fitting models with the data they have (think guacamole prices and Bitcoin). They are not picking up causal drivers. It is my belief enterprise valuation is the causal driver.

But has behavioral finance come decades too late? As Thaler put it, there was nobody like Keynes, who passed in the 1940s, to debunk a lot of the quant nonsense that came out in the 1950s-1970s – and today, it has been proven as nonsense. Buffett tried in the 1980s with his Graham-and-Doddsville, but how much can the Oracle do? Has finance reached the point of no return? Value Trap ponders that outcome, a completely nonsensical market. As you can tell, I’m super passionate about this topic, and there’s no better behavioral model to capture future expectations than enterprise valuation.

(1) Rf + factor(1) + factor(2) + factor(3)... = Rf + (estimated fair value/price – 1). The Theory of Universal Valuation posits that quantitative factor models may eventually embrace forward-looking criteria to capture the forward-looking dynamics of price-to-estimated fair value within the enterprise valuation process. The first series of factors (left) represents the framework of a traditional multi-factor quant model, while the second series (right) represents the expected return function within enterprise valuation.

By mathematical identity: (2) Factor(1) + factor(2) + factor(3)... = estimated fair value/price - 1. Historical ambiguous valuation multiples, as those used as factors in traditional quant applications, cannot theoretically capture this estimated fair-value-to-price mismatch within enterprise valuation, but only approximate it empirically by adding more potentially spurious factors.

As more and more factors are added to traditional quant factor models, they may only grow to approximate enterprise valuation more closely, but with potentially non-causal data, requiring revisions after revisions. Given the presence of FCFF, the image above shows how factors should be forward-looking to capture estimated fair value/price mismatches. Rf = risk-free rate.

Callum Turcan: The lack of proper analysis concerning causation versus correlation, and the vested interests that are dead set against doing so (investment management firms that generate large revenue streams from fees on funds where performance doesn't matter as much as maximizing AUM), allows for anyone with perceived credibility in the financial world (say a passive fund manager managing a lot of money) to point towards whatever factor they want to and say this particular thing is what's driving the market today or whenever. That sentiment is picked up by financial media outlets and grabs headlines, lending credence to the original assertion, but at no time (it seems) does the majority of market participants wonder if what they think drives market activity actually does. In many ways, that's what makes Valuentum unique. We place valuation and enterprise cash flow analysis above all else, and while we monitor daily trading activity, we don't let knee-jerk swings in the S&P 500 or “value” stocks cloud over what matters most, locating undervalued equities that the market is beginning to take notice of.

Matthew Warren: Can I make a counterpoint and see where I might be wrong? I agree that the size factor is probably guacamole and bitcoin. Same with momentum. Correlation, no causation. But I would think that high-quality companies if determined correctly should correlate and cause outsized returns. Wouldn't historical data of outsize growth, return on capital spread over cost of capital, steadiness of fundamental results, outsized cash flow production and the like point to quality. And by quality, I mean a moat. By definition, isn't a moat likely to persist? I would think that a good definition of quality might lead to outsize returns. I am not a believer in quant funds, but at one of my previous shops we used a quality screen to narrow down our investible universe. We set the parameters ourselves and then showed that those companies produced outsize returns with lower risk metrics. Granted, this was all backward-looking, but it was to prove the point that high quality fundamentals led to higher returns with less risk. Our job was then to do the fundamental research and forward-looking valuation to see if the quality (moat) would persist and that this high quality wasn't already baked into the valuation. Do you think this generally makes sense or that we were eating too many avocados?

Callum: Matt, that in many ways touches on Valuentum's Economic Castle (forward-looking expected spread of ROIC ex-goodwill over estimated WACC) and Value Creation (backward-looking ROIC ex-goodwill spread over estimated WACC) metrics we use that's required to get a VBI rating of 9 or 10.

Brian: I think there is a tremendous amount of insight that can be gleaned from robust moat analysis. We incorporate the criteria for excess economic returns into our Valuentum Buying Index (VBI) framework as well as the ValueCreation and Economic Castle frameworks as Callum mentioned. Moaty equities tend to be much more durable, and some of our favorite ideas in the Best Ideas Newsletter portfolios may have some of the widest moats and strongest economic castles, stocks like Visa (V), Facebook (FB), Cisco (CSCO), Intel (INTC), and J&J (JNJ) arguably have some of the widest moats on the market.

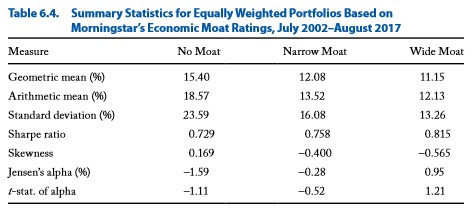

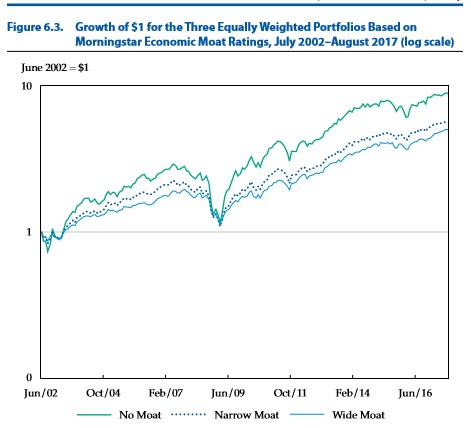

But the moat, itself, or the moat “factor” has produced rather counter-intuitive performance during the past decades. Morningstar has conducted a number of studies on their moat ratings, and here is the latest tally (source):

Morningstar started assigning moat ratings in 2002. The economic moat idea measures the quality of a business and has nothing to do with whether or not the security in question is priced fairly. The period of our analysis of economic moat and returns is July 2002 through August 2017. The number of companies that had economic moat ratings in our sample varied over time—with a minimum of 427 (July 2002), a maximum of 1,611 (November 2008), and an average of 1,039 companies.

Image Source: CFA Institute Research Foundation

Image Source: CFA Institute Research Foundation

Wide moat equities (MOAT), since Morningstar’s (MORN) inception of the rating, have significantly underperformed those of no-moat equities, by a factor of 4+ percentage points per annum over nearly two decades. That’s huge underperformance, but that’s okay, too. Morningstar analysts, when assigning moat ratings, are trying to find the best business models, and arguably one can say they’ve been very successful, as moaty equities were much more durable, had a lower standard deviation than the other two buckets. Further, the results of this moat study are consistent with the Theory of Universal Valuation, as higher risk equities, as in no-moat equities, should advance at a faster pace than moaty equities. Think of the cost of capital function in the valuation framework. Intrinsic values advance at the cost of capital, and the cost of capital is generally higher for no-moat equities.

Though many may suggest this study indicates Morningstar’s moat research is failing, I think it indicates the contrary: Morningstar analysts are identifying moaty equities, but moaty equities don’t necessarily translate to outperformance. Investors can buy great moaty companies but at the wrong prices. The cost of capital interim return function indicates that no-moat companies should advance at a faster rate that moaty companies. Because moaty companies are well-followed, in most cases, the opportunity for significant mispricings may be reduced. In short, no-moat equities may have benefited from mispricings and higher value advancement over time due to their higher risk profiles.

This moat research further supports the importance and significance of enterprise valuation. Buffett has always stated that price aside, the business/moat is then the most important consideration. That means a price-to-fair value assessment, which already embeds the qualitative considerations of a moat, should generally always trump that of the moat itself (we use the VBI as a way to assess the likelihood of price-to-fair value convergence, and a company having strong economic returns versus a big value destroyer is one criteria for this).

I wrote up a paper for the American Association of Individual Investors, which was published in the May Journal, and it goes into more why valuation is very important and why no-moats may outperform during strong bull markets and loosening credit cycles. Here is the download:

https://www.valuentum.com/downloads/20190603/download

Let me know what you think.

Callum: Very interesting Brian, and I agree that the premium investors at-large are willing to pay for moaty companies likely represents why moaty returns have underperformed no moat companies as you mentioned (it's all about getting in at the right time). This represents a key reason why we use the fair value estimate range, fair value estimate, and recent technical performance (along with other considerations like the Economic Castle rating and whether we like the industry) to pick entry and exit points, so as to not see the simulated returns in our portfolios weakened by crowding but enhanced by it. By that, I mean we try to get in on quality companies when shares are both trading below their intrinsic value and showing signs of strength, and we capitalize on investors following in after the fact even if that pushes shares of the company in question above our fair value estimate, where we then exit the position if/when technicals turn against us and the crowding effect is now working the other way.

Matt: Thanks for the thorough and thoughtful reply. I find the return data from Morningstar hard to swallow. In fact, it makes me want to question whether the firm properly captured total return, accounted for survivorship bias, etc. I remember covering no moat Anchor Glass and getting the direction right as it went to zero. I don't remember any moaty companies going to zero on the industrial team. Do you reckon Morningstar captured this dynamic when running the numbers?

One other thing that occurs to me is the starting point of the data set is in the 2002 recession. In my experience, no moat stocks get beaten down the worst during downturns due to bankruptcy or permanent capital impairment risk, and then come screaming higher out the other side in relief rally. I also wonder about mischaracterization of moats. When I took over the financial team, there had already been bankruptcies of firms that had been rated with moats, which looks simply like a mischaracterization in hindsight -- and maybe the higher returns of no moat are just for assuming higher risk or a higher discount rate as you mentioned. You carry the risk of permanent capital impairment if there is a depression and then hope that one doesn't happen during your career? Those are the various thoughts I had trying to pooh-pooh the data that you laid out so clearly in front of me. I might be tilting at the proverbial windmill?

Also, when we characterized moaty companies as those with the highest quality fundamentals (with perfect hindsight) in other countries such as South Africa (EZA), for example, and then ran the stock performance, it showed higher returns with lower volatility. I wasn't in charge of this project, though, and cannot say it was done theoretically correctly. Based on my reading of your book, I think the mathematics of our previous work might have been off base? Specifically, it was perfect hindsight and based on historical performance.

Another thought that occurred to me is that Warren Buffett himself largely walked away from cigar butts and no moat companies in his purchases over the years, except for some of his errors like Dexter Shoes. He credited Charlie Munger steering him towards the importance of wide moats as the only place to fish. I always thought he put moats first and valuation second in the past long while? I stand to be corrected, though.

My experience and intuition are that modeling no moat companies can be a lot like quesswork. It is hard to predict the future when the company has 10 competitors in a highly cyclical and commodified industry. You have to guess when the cycle (magnitude and duration) is going to turn based on macro. With moaty companies, I feel a lot more confident that my perpetuity value actually is rooted close to future reality. For this reason alone, I feel more comfortable investing in cheap moaty companies than cheap no moat companies. I'm more confident in the "cheapness."

The thing that I can't argue is that you can underpay or overpay for any company. That is true for sure. And therefore, valuation is of paramount importance. It's also clear to me that you have thought about all of this more thoroughly than I have and I'm looking to catch up!

Brian: Great insights as always Matt. One of the things that Richard Thaler said in his book Misbehaving is that investors are just looking “to buy stocks that will go up in value—or, in other words, stocks that they think other investors will later decide should be worth more. And these other investors, in turn, are making their own bets on others’ future valuations.”

I think, regardless of any strategy, that is what long investors are trying to do: find stocks that will go up. There’s the implicit assumption, however, that good companies, moaty companies will always be the best kinds of stocks over time, as their fundamentals may translate into compounding economic returns over time. But economic returns aren’t necessarily the key drivers behind stock prices/returns, even if they are related. It comes down to what Michael Mauboussin has explained as “expectations revisions.”

For example, there could be a moaty company that everyone expects to compound capital and economic returns for decades at significantly high rates. However, if this company comes up a little short on these high-economic-return expectations, its shares could underperform those of a company with lower relative economic returns but outperforms fundamentally, as the market continuously must ratchet the expectations (enterprise valuation) of the lower-economic-return company higher, driving share price outperformance. From the May AAII Journal article:

Is a no-moat’s economic value trajectory correctly priced in? Is a wide moat’s economic value trajectory overvalued? Is a no-moat company’s economic value trajectory undervalued? The economic moat concept alone is less important than an evaluation of how the market has priced a company’s future economic value stream, or whether the marketplace is valuing the equity correctly within the enterprise valuation construct. This means that investors should be looking for companies in the global investment universe that have mispriced future economic value streams (i.e., stocks that are underpriced relative to their discounted future free cash flows—meaning the future expectations of how the business will perform—and net balance sheet), not whether a company has a wide economic moat or a narrow one, per se.

I haven’t seen the raw data from Morningstar, but I have no reason to believe it is not accurate. I remember making some fantastic calls at Morningstar, as well (I remember calling a number of no-moat airline bankruptcies; Frontier Airlines comes to mind as one), but these stocks going to $0 may be completely offset by others. For example, let’s take the following example that might be in the data as an anecdote. Netflix (NFLX) was rated one-star in December 2004, with a no-moat rating and a fair value estimate of $8 per share (it was trading at $12.33 at the time). The stock now trades for nearly $300 per share, and this is after a 7-for-1 stock split in 2015! To put this into perspective, the stock is up 23x on a pre-split basis, 166x including the split. It would take a lot of no-moat calls going to $0 to offset this call alone [Netflix is currently rated Narrow Moat at Morningstar.].

That said and to your point, moat analysis is very valuable (duration of economic returns), and we love economic castle analysis, too (magnitude of economic returns). As you mention as well, investors can often be much more confident in the business models and valuations of moaty companies, but the investment question generally and eventually comes down to enterprise valuation or whether the market is capturing expectations of the moat correctly. A moat overlay can be applied to enterprise valuation to help increase confidence in the undervaluation thesis, and we believe a variety of factors, including economic-return (castle) analysis, technical/momentum indicators and forward relative (behavioral) valuation can be applied to free-cash-flow modeling to increase confidence in the undervaluation thesis.

I think of the momentum/technical overlay in our process as an added layer of conviction to steer investors away from value traps, but as I think more about the benefits of the momentum/technical overlay in the context of our conversation, it might also be effectively used within the moat process. A momentum overlay, for example, would have steered investors away from a lot of the bank moats prior and during the Financial Crisis, just as it also would have steered investors away from banks they thought were undervalued as they continued to fall (“value traps”). A lot of legendary value investors like Bill Miller would have steered clear of investments in Countrywide Financial and Bear Stearns, too, if they had heeded the “information contained in prices,” something I talk a lot about in Value Trap.

As we wrap up, here are two quotes from the Oracle of Omaha:

“I could give you other personal examples of ‘bargain-purchase’ folly but I'm sure you get the picture: It's far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price. Charlie understood this early; I was a slow learner. But now, when buying companies or common stocks, we look for first-class businesses accompanied by first-class managements.” – 1989 Letter

“Leaving the question of price aside, the best business to own is one that over an extended period can employ large amounts of incremental capital at very high rates of return. The worst business to own is one that must, or will, do the opposite - that is, consistently employ ever-greater amounts of capital at very low rates of return.” – 1992 Letter

Great conversation all!

Related factor ETFs: MTUM, PDP, MOM, FDMO, VAMO, DWAQ, MMTM, SWIN, BEMO, JMOM, ULVM, QVAL, BFOR, PWC, FAB, VLUE, VUSE, QUAL

Related cryptocurrency: BTC, GBTC

Join the conversation. Leave your thoughts below. What’s your favorite Buffett quote?

1 Comments Posted Leave a comment