4 Very Good Reasons Why We Don’t Like Dividends of Banking Stocks

Untermyer: Is not commercial credit based primarily upon money or property?

Morgan: No, sir. The first thing is character.

Untermyer: Before money or property?

Morgan: Before money or anything else. Money cannot buy it … a man I do not trust could not get money from me on all the bonds in Christendom.

--Mr. JP Morgan’s testimony before the Pujo Committee (questioning from Samuel Untermyer), 1912-1913

Image: Bank Run in Michigan, USA, February 1933. Source: Public Domain.

By Brian Nelson, CFA

It’s sometimes easy to lose sight of the fragility of a banking firm’s business model. Let’s examine the reasons why we don’t like banking firms’ dividends. Reason #1: A Bank Run Is Always Possible. Reason #2: Others Have Tried to Invest in Bank Dividends and Have Failed. Reason #3: Cash Flow Is Not Meaningful at Banks. Reason #4: There Are Plenty of Other Options.

Reason #1: A Bank Run Is Always Possible

Reason #1: A Bank Run Is Always Possible

Though the history of banking dates back to as early as 2000 BC in Babylonia, the makings of the present-day banking system in the U.S. really didn’t take hold until the beginning of the 20th century. Some financial historians may argue for a later date, but we think the Panic of 1907 is of particular importance, where the core of the fragility of the banking system was highlighted yet again in this episode (shown right), which followed two other well-known panics in 1893 and 1873.

Also dubbed the Knickerbocker Crisis, the Panic of 1907 primarily came about from lost confidence driven by the failed attempt by Otto Heinze and company to corner the market in shares of United Copper. Once the attempt failed, shares of United Copper collapsed, bringing down with it Heinze’s brokerage house (Gross & Kleeberg) and causing the insolvency of the supporting bank (State Savings Bank of Butte Montana). However, it wasn’t until the association of Heinze and the Montana bank to the Mercantile National Bank in New York City did a panic actually spread.

Depositors, stripped of their confidence in the banking system as a result of the string of events to this point, began withdrawing deposits en masse. The panic extended to one of the largest banks in the U.S., the Knickerbocker Trust Company, where in but a few hours it was forced to suspend banking operations as a result of hefty withdrawals. Then two other large trusts, the Trust Company of America and Lincoln Trust Company, started facing runs, followed by a number of other banks. Confidence in the banking system had been shaken to the core, and creditors that were willing to lend money just a few weeks before were now hunkering down with any capital they had left. It wasn’t until Mr. J.P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller came to the aid of America’s credit that the panic finally subsided.

Just a couple of decades later, America saw yet another crisis of confidence during the Crash of 1929. Margin requirements were so thin back in the 1920s that brokers were left holding the bag when stocks collapsed and investors could not settle debts. During the first months of 1930, more than 700 U.S. banks failed and the financial institutions left standing built up reserves (and stayed far away from expanding their loan books), creating one of the greatest depressions our world has yet seen.

Just a couple of decades later, America saw yet another crisis of confidence during the Crash of 1929. Margin requirements were so thin back in the 1920s that brokers were left holding the bag when stocks collapsed and investors could not settle debts. During the first months of 1930, more than 700 U.S. banks failed and the financial institutions left standing built up reserves (and stayed far away from expanding their loan books), creating one of the greatest depressions our world has yet seen.

Most investors credit the Great Depression as the primary cause for the creation of the Securities and Exchange Commission in 1933 and the passing of the Glass-Steagall Act, which separated commercial banking operations from investment banking endeavors. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act subsequently repealed part of Glass-Steagall in 1999, allowing the combination of a variety of banking, insurance, and securities-related operations.

Enter the Financial Crisis of 2008 and the Great Recession

We firmly believe that an investment in a bank must come with the acknowledgement of the distinct possibility that another financial crisis may occur at an unknown time in the future. Why? Banks do not keep a 100% reserve against deposits. Our good friend George Bailey knew this very well when he tried to discourage Bedford Falls residents from making a “run” on the famous and beloved Building and Loan.

In the words of Mr. J.P. Morgan, character is the only thing that matters in banking--or said differently, perceived confidence that the banking system will continue to work is really the duct tape that holds the financial markets together. Once this perceived confidence breaks down as it has many a time before, a “run on the bank dynamic” occurs. Such a unique risk will always be present for banking firm investors relative to investors in general operating corporations.

All else equal (especially valuation), we prefer general operating corporations with hefty Valuentum Dividend Cushion ratios to any banking firms that have equal (or even higher) dividend yields. We think non-bank dividend growth options are plentiful, and we just don’t want or need to be bothered with the added risk of banking firms in our dividend growth portfolio.

Note: We have modest banking exposure in the portfolio of our Best Ideas Newsletter via a diversified ETF, the Financial Select Sector SPDR (XLF), primarily for diversification and valuation reasons.

Reason #2: Others Have Tried to Invest in Bank Dividends and Failed

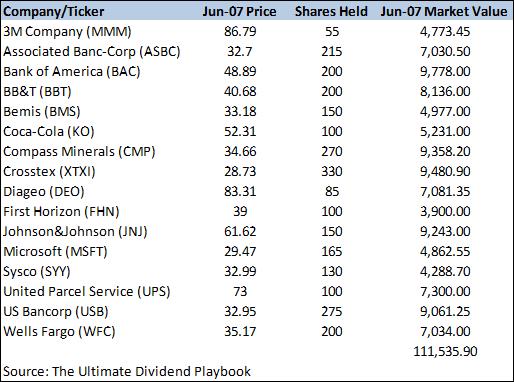

In turning to page 178 of Morningstar's (MORN) publication, The Ultimate Dividend Playbook, the research firm showcases a managed portfolio that it calls the Dividend Builder Portfolio, which means the portfolio seeks to hold constituents with increasing dividends. Here's the portfolio as shown in the book.

The above is a real-money portfolio (the positions are not hypothetical). In June 2007, this portfolio was yielding 3.3%. Let's say you were a big fan of dividend-paying banking firms and held on to them because they had nice yields. In fact, Morningstar went on to say in the book--same page--that "if the market were to close for the next five years...I don't think I'd make many changes, if at all."

Well, things didn't work out great, especially for banking entities. Associated Banc-Corp (ASBC) cut its dividend January 2010, BB&T (BBT) cut its dividend in May 2009, US Bancorp (USB) cut its dividend March 2009, Wells Fargo (WFC) cut its dividend in March 2009, First Horizon (FHN) cut its dividend in January 2008, and Bank of America (BAC) cut its dividend October 2008. Interestingly, even energy firm Crosstex (XTXI) cut its distribution October 2008.

Others focused on the long term and on Warren Buffett’s economic moat did not foresee the inevitable long-term risks inherent to investing in dividend-paying banking stocks, and we will not expose our members to the same financial catastrophe, of which we know the risks well. We’re not going to do it.

Reason #3: Cash Flow Is Not Meaningful at Banks

Valuentum members know that cash flow analysis is the most critical component of our assessment of a firm’s ability to keep paying investors dividends long into the future.

In corporate finance, there are generally three types of free cash flow: traditional free cash flow (cash flow from operations less capital expenditures); free cash flow to the firm (as used in enterprise valuation); and free cash flow to equity (which is applied to banking and insurance firms).

Though we think traditional free cash flow and free cash flow to the firm are acceptable methods for calculating the intrinsic value of general operating corporations, our valuation methods apply a residual income model to assess the value of banking and insurance firms, as we have significantly reduced confidence in the use of free cash flow to equity as a way to value banking entities.

But why? Free cash flow at banks is nearly impossible to assess because banks use cash to generate cash. Other firms, on the other hand, use non-cash assets to generate cash--a subtle but important difference.

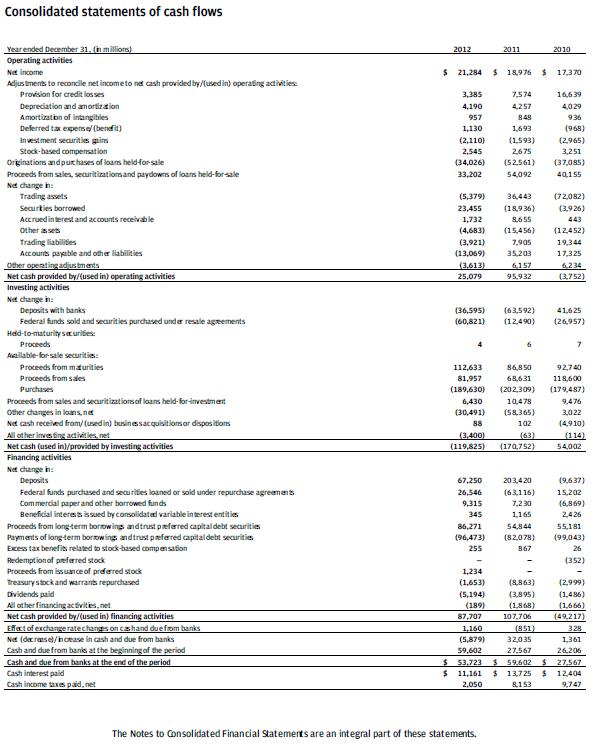

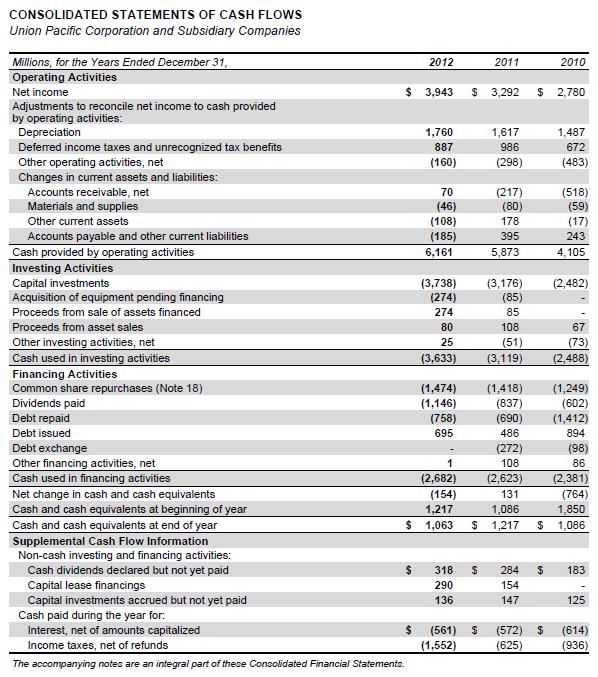

A look at JP Morgan’s (the company) cash flow statement compared to that of a general operating corporation such as Union Pacific (UNP), for example, is perhaps all that may be necessary to illustrate this point. Where traditional free cash flow (cash flow from operations less capital expenditures) can be calculated rather easily at Union Pacific (second image below), it’s nearly impossible to come away with a meaningful free cash flow figure at JP Morgan, in our view.

Quite simply, cash flow from operations and capital expenditures are relatively easy to forecast at Union Pacific, but they are nearly impossible and borderline meaningless for banking companies.

JP Morgan’s Cash Flow Statement

Image Source: J.P. Morgan

Union Pacific’s Cash Flow Statement

Image Source: Union Pacific

We’re not saying that we don’t understand how to analyze banking stocks. Quite the contrary, it is because we understand the banking business model well that we don't like them.

We fully understand traditional analysis in how to assess the attractiveness of a banking entity and how to value them in good times. In times of panic or distress, however, all bets are off. We don’t think it’s all that easy for anyone to ascertain the dividend strength of any banking entity through the course of the economic cycle, particularly given the ever-present risks of bank runs during times of panic or distress, their opaque loan books (securities portfolios) and arbitrary cash flow generation.

Others have tried to incorporate meaningful banking exposure into dividend-paying portfolios, and they just haven't been successful. We refuse to expose our members to dividend growth positions that we’re not completely confident in--and it is our view that nobody can be confident in the future dividend growth profile of a banking entity.

Reason #4: There’s Plenty of Other Non-Banking Firm Ideas

Frankly, we just don’t see the need for us to take the leap into the banking sector just for dividends. That’s why we don’t have any banking exposure in the Dividend Growth Newsletter portfolio. It’s not that we forgot about a sector in our portfolio construction--it is that we don’t want our members to face the prospects of any dividend cuts...ever.

We want to have conviction in the long-term dividend strength of the companies of the portfolio. That’s the Valuentum way, and our members love it!

Valuentum does not believe the long-term dividend health of any financial institution can be accurately predicted. We continue to believe the best dividend growth ideas are in the Dividend Growth Newsletter portfolio.

----------

NOW READ

The Silicon Valley Bank collapse recalls the tussle over the accounting for financial instruments after the global financial crisis [GFC] in 2009, particularly the debate about whether some financial instruments should be carried at amortized cost (held-to-maturity, HTM) rather than at fair value (available-for-sale, AFS), or what is referred to as the “mixed measurement model.” -- Sandy Peters, CPA, CFA

To read the article on the CFA Institute Blog >>

----------

Image Source: FDIC

"Unrealized losses on securities totaled $683.9 billion in third quarter, up $125.5 billion (22.5 percent) from the prior quarter, primarily due to an increase in mortgage rates that reduced the value of mortgagebacked securities. Unrealized losses on held-to-maturity securities totaled $390.5 billion in the third quarter, while unrealized losses on available-for-sale securities totaled $293.5 billion." -- FDIC Quarterly

----------

A version of this article appeared on our website September 4, 2013.

Brian Nelson owns shares in SPY, SCHG, QQQ, DIA, VOT, BITO, RSP, and IWM. Valuentum owns SPY, SCHG, QQQ, VOO, and DIA. Brian Nelson's household owns shares in HON, DIS, HAS, NKE, DIA, RSP, SCHG, QQQ, and VOO. Some of the other securities written about in this article may be included in Valuentum's simulated newsletter portfolios. Contact Valuentum for more information about its editorial policies.

Valuentum members have access to our 16-page stock reports, Valuentum Buying Index ratings, Dividend Cushion ratios, fair value estimates and ranges, dividend reports and more. Not a member? Subscribe today. The first 14 days are free.

0 Comments Posted Leave a comment