Currency: Cases in Probabilistic Thinking

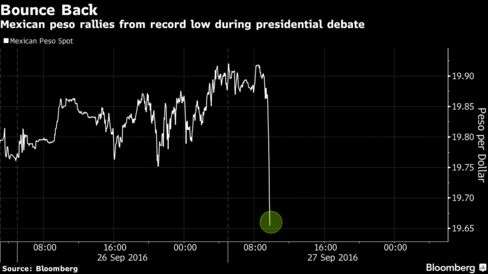

The rally in the Mexican peso relative to the US dollar during the first Trump-Clinton debate of 2016 showcased the increased likelihood of a Clinton victory, in light of Trump's current political agenda. Instances like this, where currency markets serve to act as a probability indicator of the likelihood of a future event, have occurred through the course of history, the most fasinating of which happened during the American Civil War and with Confederate scrip specifically.

Image Source: Bloomberg, "Mexican Peso Gives Clearest Signal Trump Lost Debate"

By Brian Nelson, CFA

At Valuentum, we talk a lot about how markets act as "discounting" mechanisms of the probability of future events, and more specifically as it relates to stocks, how a company's share price reflects the implicit probabilities assigned to future free cash flow trajectories of the company by the market. By extension, changes in equity prices therefore reflect a change of opinion by the market in the percentage it implicitly assigns to each of the company's future probable free cash flow streams or a change (a shift) in the magnitude or composition of the range of a company's probable free cash flow streams altogether.

The currency markets reflect this probabilistic dynamic, too. For example, the rally in the Mexican peso relative to the US dollar during the first Trump-Clinton debate of 2016 showcased the increased likelihood of a Clinton victory, in light of Trump's current political agenda. Instances like this, where currency markets serve to act as a probability indicator of the likelihood of a future event, have occurred through the course of history, the most fasinating of which happened during the American Civil War and with Confederate scrip specifically. Let's take a trip back in time.

The Confederate dollar, nicknamed the “Greyback,” had not been secured by hard assets but only by a promise to pay the bearer, much like the US dollar today. The South’s self-embargo intending to starve Europe of cotton, the blockade of Southern ports by the Union, and the individual states’ rights mantra that hurt tax receipts were contributing factors to runaway inflation in the Confederacy. An increase in the South’s money supply, by a factor of 20 near the end of the war, and infamous Northern counterfeiter Samuel C. Upham, whose fake notes may have accounted for 1%-2.5% of all of Southern outstanding, would serve to place continued pressure on the price of Confederate money. By the end of the war, a cake of soap would reportedly sell for as much as $50 CSA.[i]

The fluctuating price of the Greyback during the American Civil War, however, could also be viewed in part as a reflection of Southern opinion of the probability that the South would eventually win the war. In the early years of the conflict, for example, the Greyback had high purchasing power as the probability of a peaceful settlement with the Union seemed especially high, in light of the potential for a foreign power to recognize the South and as Abraham Lincoln dealt with disappointment after disappointment, not the least of which was the country’s revolving door of Union generals. It perhaps wasn’t until the realization by Southerners that it would be a long and bloody war after the Battle of Antietam in September 1862 and the North’s passing of the US Conscription/Finance Bill in March 1863 that confidence may have truly broke, if not openly at the time than reflected in the price of Confederate currency.[ii]

The South’s loss of Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson due to “friendly fire” after the Battle of Chancellorsville, the “rebel” surrender at Vicksburg, Mississippi, to U.S. Grant, which severed the Confederacy in two, and the dear price that Southerners paid on those three fateful days in July 1863 near that small Pennsylvania town, each contributed uniquely to the ongoing decline of the price of Confederate money. The Currency Reform Act of 1864 would help stem the decline in the price of Confederate money somewhat by reducing the money supply by one third, but the eventual Fall of Atlanta and Union General William Tecumseh Sherman’s “March to the Sea” would remind holders of Confederate scrip of the inescapable reality, that their sacrifices were a lost cause, that they would not win their independence, that a new nation would not be hatched, at least not the one they had been fighting for.[iii]

Pictured: Key battles and events during the American Civil War impacted the price of Confederate currency, while the overhang of the expanding supply of money and counterfeiting helped contribute to the overall downward trend.

Through the course of the conflict, citizens of the Confederacy may have, indirectly or directly, used war news in part to handicap the likelihood that they would be repaid in the event of a peace treaty with the United States. In forming the price level of Confederate scrip at any time during the war, forward-looking Confederate citizens, by doing so, were also implicitly quantifying the probability, in their collective view, that the South would eventually prevail. In the summer months of 1862, for example, with the Greyback quoted at 50 cents in gold, Southerners implicitly believed the chances were about even that they would win their independence. By the end of 1863, however, with the Greyback quoted at 6 cents in gold, chances were pegged at 6%, and by the time the armies had converged at a small town in Virginia called Appomattox Courthouse, Confederate notes essentially being worthless, the chances of a victory practically nil.[iv]

The probabilistic mechanism that resulted in the ongoing depreciation of the price of the Greyback speaks to a classic and infinite truism in finance: Assets will always be priced, and their values estimated, in part on the basis of future expectations, with little regard to the past, whether it is a stock that is valued on the basis of future expectations at any time in the future, or Confederate currency that is priced on the basis of the probability of a Southern victory and repayment at any time during the American Civil War. That the bells of secession brought cheers to the South in 1861, for example, mattered little to the eventual price of the Greyback, which was forever doomed when Confederate General Robert E. Lee signed the generous surrender terms from U.S. Grant on the fateful day at the Wilmer McLean House in April 1865.

To understand the functioning of markets, one must "think probabilistically..."

Related ETFs: AYT, BZF, CCX, CEW, CNY, CYB, DBMX, DBV, ERO, EUFX, EWW, FXA, FXB, FXC, FXCH, FXE, FXF, FXS, FXSG, FXY, GBB, HEW, ICI, ICN, INR, JEM, JYN, PGD, MEX, SMK, UDN, UMX, USDU, UUP

-------------------------

[i] Marc Weidenmier, "Bogus Money Matters: Sam Upham and His Confederate Counterfeiting Business" Business and Economic History 28 no. 2 (1999b): 313-324.

[ii] Marc Weidenmier, Claremont McKenna College, Money and Finance in the Confederate States of America, EH.net, accessed October 6, 2015. https://eh.net/encyclopedia/money-and-finance-in-the-confederate-states-of-america/

[iii] Marc Weidenmier, Claremont McKenna College, Money and Finance in the Confederate States of America, EH.net, accessed October 6, 2015. https://eh.net/encyclopedia/money-and-finance-in-the-confederate-states-of-america/

[iv] Marc Weidenmier, Claremont McKenna College, Money and Finance in the Confederate States of America, EH.net, accessed October 6, 2015. https://eh.net/encyclopedia/money-and-finance-in-the-confederate-states-of-america/